In May 1960, four men gathered in Jean Marchand’s room at the Mount Royal Hotel in Montreal to discuss whether they would be candidates for Jean Lesage’s Quebec Liberal Party: Marchand, Gérard Pelletier, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, and René Lévesque. For a variety of reasons, Lévesque was the only one prepared to make the leap, and he walked over to the Windsor Hotel to let Lesage know that “the others just aren’t ready.”

Jean Provencher quoted Lévesque as saying this in his 1973 biography. Lévesque recalled saying it in his 1986 memoir. And I used the anecdote in my own book about the Parti Québécois. But Jean-François Lisée consulted the accounts of the others placed in the room that night, and none of them mention being together. It is a small but telling example of the rigour that Lisée used in checking and double-checking the versions given by Lévesque and Trudeau, now almost mythical figures to those under forty-five.

The Trudeau papers are accessible today at Library and Archives Canada, and Lisée and the retired political scientist Guy Bouthillier have both been poring over them. (Two previous biographies, by John English and Max and Monique Nemni, required special permission from the family.) Both authors are committed sovereigntists, but Lisée, a journalist and former leader of the Parti Québécois, gives a more balanced and nuanced account than Bouthillier, who bristles with indignation at what he considers Trudeau’s betrayal of his youthful nationalism and the French Canadian part of his identity.

In Pierre Elliott Trudeau: Le Bagarreur, Bouthillier uses the theme of Trudeau as a street fighter — the dictionary definition of bagarreur is “brawler”— citing his diary again and again as he describes scuffles and fist fights. “At times, it was to settle an account with someone bothersome,” Bouthillier writes. “But more often, he provoked the brawl for no reason, for the simple pleasure of testing his courage and his talents as a boxer using the technique of surprise attacks!” For Bouthillier, Trudeau spent his youth wrestling with an identity crisis. Was he a French Canadian? An English Canadian? A good Catholic? A sinner?

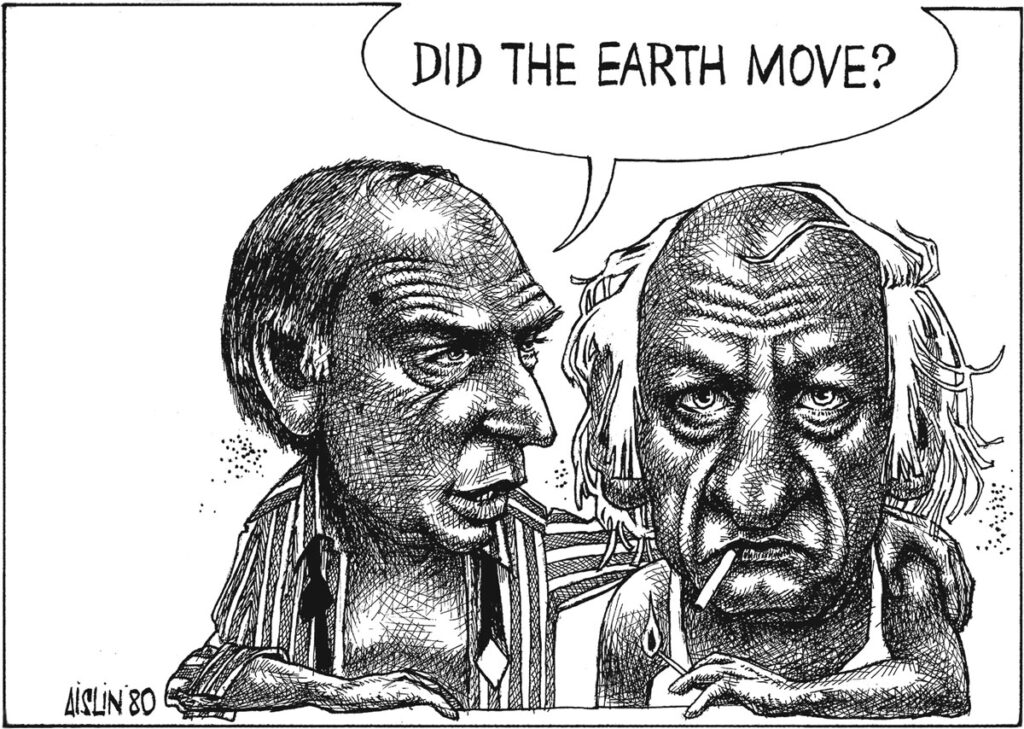

The odd couple graced the front page of the Montreal Gazette after the 1980 referendum.

Aislin; Montreal Gazette, May 21, 1980

While Trudeau was studying at Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf, a prestigious classical college in Montreal where he excelled academically and athletically, he wrote a play entitled Dupés (Duped). In it, a French Canadian merchant organizes a contest for the hand of his daughter: her suitors must run his store for a day. Trudeau played the principal character, Ditreau, who disguises himself as a Jew and calls himself Goldenburg. Then, as an anglicized French Canadian, he changes the name of the store and puts up English signs. The owner, outraged, calls the suitor a coward and a traitor and refuses to let him marry his daughter. Throughout, the Jews are treated as antisemitic caricatures, the French Canadians as corrupt simpletons.

Bouthillier recounts the story of the play and the reactions of Trudeau’s previous biographers. The Nemnis blamed the Brébeuf environment for the antisemitic and xenophobic nature of the nationalism expressed in the play, while English cited the omnipresent antisemitism in the federal government at the time.

“Not a word, not a single one, by any of these authors on the denigrating comments that Ditreau uses constantly against French Canadians,” writes Bouthillier. “One can regret this silence. One can also explain it. For these biographers, in effect, Pierre Elliott Trudeau was a hero, and doubly so: the hero of their biographies and the hero of their country.” To show young Trudeau’s contempt for his own people and his desire to change his own identity would have been unthinkable for them, he argues.

Bouthillier sees each change in Trudeau’s position as either disloyalty or an attempt to cover his antisemitic right-wing tracks, so they wouldn’t blemish his future career. Thus, it is at Harvard that he realizes that his factional readings and enthusiasms during the Second World War would be obstacles to the goal he had determined for his life: “governing the people of his country.”

“After the war, he stopped defending the cause of separatism, as he would forbid himself — until the end of his life! — from acknowledging that he had previously been a resolute partisan,” Bouthillier writes. “A silence that enlightens us about the limits of intellectual honesty as he conceived it.”

Both Bouthillier and Lisée have made good use of Trudeau’s journal and his careful notes on what he read, and both note his admiration for Charles Maurras, the right-wing French proto-fascist. Bouthillier suggests that, when Maurras was convicted and imprisoned after the war for sharing intelligence with the enemy, Trudeau learned that “it is never good to find oneself in the camp of the defeated” and that he should forget what he had once been part of.

In Lévesque/Trudeau, Lisée is less interested in denunciation and more committed to finding out what his two subjects thought, and when and why. He tells the story of Dupés much more concisely than Bouthillier, for instance, without indignation. He’s focused on peeling away the layers of convenient narrative that both men applied like sunscreen to their public personas, revealing the twists and turns in their accounts of their lives and showing how much they had in common.

So Lévesque invented a meeting of his friends on the eve of his decision to run for office, just as he had invented seeing Mussolini and his mistress strung up by the heels by an angry mob. Trudeau presented himself to his biographers as a non-conformist and anti-nationalist at Brébeuf, suggesting that his federalist commitment was entirely consistent with the positions of his youth, while in fact he had been a fervent nationalist as a young man, addicted to the works of Maurras — what Lisée calls “the hard drug of the extreme right”— and a leading member of a separatist secret society.

Lisée underlines how, at Harvard, Trudeau came to question his own opposition to conscription and Canada’s participation in the war, even though he had pulled strings to avoid service. “Will that be a great regret?” he wrote a friend in 1945. “During my whole life?” Lisée observes, “He grasped, a little late, that he was on the wrong side of this debate, on the wrong side of history, he who wrote that he was against the war, the mobilization, the assistance to the belligerents.” He theorizes that this was one of the reasons that Trudeau would seek out danger during his world travels — to prove to himself that he was not a coward.

Lisée also pinpoints when Trudeau became a federalist and the reasoning behind the decision. While Bouthillier sees Trudeau as personally torn, Lisée discerns a pragmatic analysis based, in part, on the introduction of universal hospital insurance by Tommy Douglas’s Co‑operative Commonwealth Federation government in Saskatchewan on January 1, 1947. In an unpublished article, which Lisée sees as critical, Trudeau even recommended taking control of education in Quebec away from the Church. A step too far for Le Devoir.

Like Bouthillier, Lisée identifies that Trudeau was at risk when he published his book on the four-month Asbestos strike of 1949 and his articles in Cité libre attacking Quebec nationalists: “He is at risk of being recognized, denounced, unmasked as one who, barely fifteen years earlier, supported what he abhors today: an independent Quebec, Christian and totalitarian, imposed by force.” In contrast, Lisée points out, the journalist André Laurendeau renounced his own antisemitic remarks from the 1930s, which he described in 1963 as “dreadful speeches.”

Lisée’s book offers significantly more than just a series of nagging corrections of the self-serving accounts of two major figures in twentieth-century Canada. In moving back and forth between the lives of the young men, he highlights the network of connections that kept them apart and then drew them together. Lévesque was an internationalist — a war correspondent with the U.S. Army — who became a nationalist. Trudeau was a nationalist — he protested against conscription — who became a federalist. They were united in their opposition to Quebec’s reactionary Union Nationale premier, Maurice Duplessis.

In addition to making Duplessis part of the narrative, Lisée introduces another factor in the political life of postwar Quebec, the secret Ordre de Jacques-Cartier. He shows how this clandestine network quietly supported the financially fragile newspaper Le Devoir and the Asbestos strikers — support not mentioned in Hugues Théorêt’s 2024 book about the society, La Patente.

Both Trudeau and Lévesque became engaged in the Radio-Canada strike of 1958–59, when seventy-four producers fought for union recognition. It was just one of the labour disputes that Trudeau had been involved with, but it was a first for Lévesque. If it was part of a sequence for the former, it reshaped the latter.

Lévesque was a freelancer at the time, no longer an employee of Radio-Canada, and he was slow to take part in the conflict. But when he did, in the winter of 1959, he threw himself into it with all of his energy, writing bulletins, strategizing, and speaking. He offered an episode of his famous television program, Point de mire, Lisée explains, “but one focused on the strike, its origin, the stakes, the tactics. It was supposed to be three benefit-performance nights. But the Comédie Canadienne on Sainte-Catherine — the future Théâtre du Nouveau Monde — was always full.” Given the interest, “they put on sixteen performances there, to full houses, before going on tour to Sherbrooke, Hull, and Ottawa. In Quebec City, the presentation was in the Colisée. It was THE show of the cultural season.” Indeed, it raised $20,000 — the equivalent of $215,000 today.

The Radio-Canada strike and the indifference of John Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservative government to it were a transformative experience for Lévesque. “The wall of refusal, the incomprehension, the absence of solidarity, even empathy, moved something in the mind of the thirty-seven-year-old journalist,” Lisée writes. “It is at this moment, exactly, that a real nationalist feeling is born.”

As Lévesque vented his frustration about the lack of concern among his anglophone colleagues and their unions to André Laurendeau, then chief editorial writer at Le Devoir, he concluded that the reason was that the striking producers were Montrealers and francophones.

“I am watching where you are going, you are in the process of transforming into a nationalist,” Laurendeau told him. “That can lead you a long way.”

“I don’t know,” replied Lévesque softly. “Perhaps . . .”

On March 7, 1959, in time for the Stanley Cup playoffs, an agreement was signed ending the dispute. Fourteen months later, Lévesque was a candidate for Jean Lesage’s Quebec Liberal Party.

Bouthillier’s account is marked by a still bitter sense of betrayal. Lisée’s quivers with the thrill of discovery and the excitement of surprise at the details unearthed about the principal characters and others, including Duplessis (who knew he was a great reader?) and Jean Drapeau (who knew that Montreal’s mayor called for a dramatic transfer of powers to Quebec in 1959?), who played important roles.

For Lisée, Lévesque/Trudeau is the first of three double biographies, apparently self-published with the support of the Fondation René-Lévesque, the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation, the Fondation Maurice-Séguin, and the Fondation Lionel-Groulx. Although the intellectual traditions and loyalties of the four foundations are quite different, none of them should be disappointed.

Graham Fraser is the author of Sorry, I Don’t Speak French and other books.