The Yellowknives Dene First Nation has watched as its ancestral land and waters have been penetrated to extract gold since the Con Mine began operating in 1938, followed by the Giant Mine, which opened in 1949. With The Price of Gold, the historians John Sandlos and Arn Keeling, from Memorial University, offer thoroughly documented evidence of the damage inflicted.

As with the better-known Mackenzie Valley Pipeline proposal, the subject of the Berger Inquiry, environmental concerns were front and centre for community-minded activists in the North in the mid-1970s. Conscious of the threats from the mines, campaigners persistently pursued their goal: expose and correct the leakage of arsenic trioxide dust and poisonous seepage into Yellowknife Bay. Hardest hit by years of exposure were homes at what was known as Rainbow Valley, on Latham Island near Giant.

Local Indigenous people fell victim to the “historical experience of colonialism” when the mines destroyed traditional hunting and fishing grounds. “From the beginning,” Sandlos and Keeling write, “the mining companies were largely indifferent” to the contamination. Also indifferent were the three levels of government, as well as the territorial weekly News of the North. Unlike its competitor, the Yellowknifer, it consistently sided with reports that downplayed potential dangers. The paper sidestepped the fight against mine pollution, backing the owners and their official protectors, who argued that closing Giant would cost 300 to 400 jobs and devastate the economy. Governments of “all political stripes,” Sandlos and Keeling write, “have long resisted imposing strict environmental regulations on resource companies, lest they compromise production rates (and the resulting royalties and taxes), local employment, or even the very survival of a development project.”

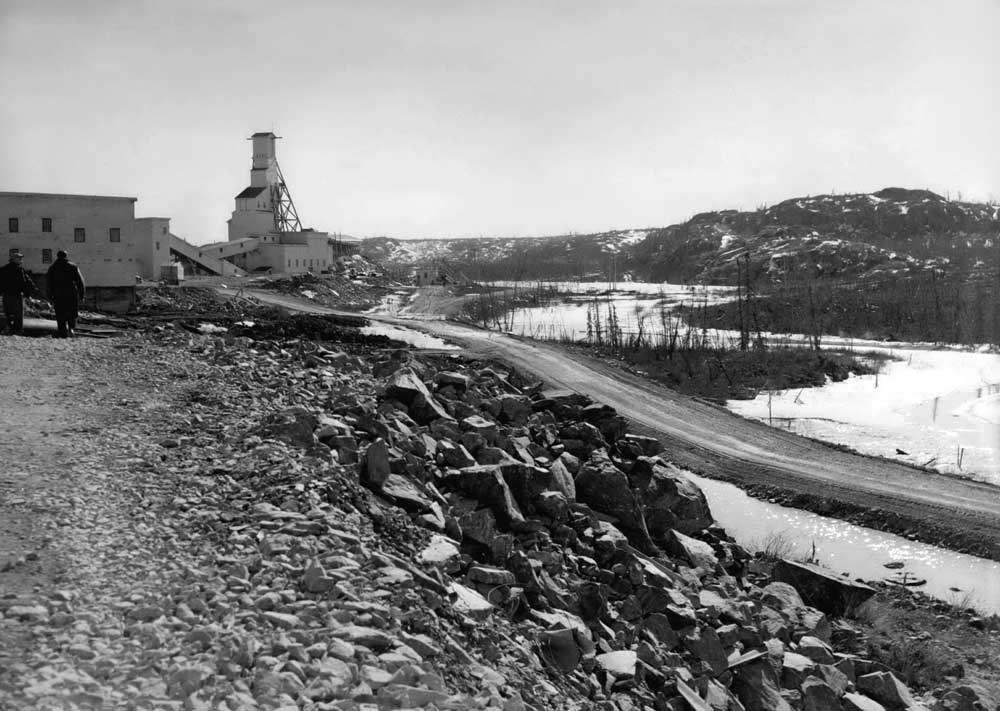

The Giant Mine as it appeared during a royal visit by the Duke of Edinburgh in 1952.

Keystone Pictures USA; ZUMA PRESS; Alamy

Academic writers can clutter their prose with obfuscating terms. Not these two. Sandlos and Keeling have backed up their history with clear-eyed research and deep digging into fact-filled reports, some of them hidden from public view. Although making every effort to be fair, they are certain of their mission to expose wrongdoing. They show that the fight against corporate actors was a rare collaboration among environmentalists, First Nations advocates, and trade unionists. Early on, the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers led the way, with the United Steelworkers of America assuming the advocacy role after the two unions merged in 1967.

Union leaders were concerned about the health and safety of their members, but they also saw the bigger picture of First Nations and other communities facing an arsenic-poisoned workplace and water supply: “The resurgent activism among organized labour was consistent with a new era of anti-pollution activism among the broader public in the early 1970s.” When the collective community voice demanded that the companies — Falconbridge, Cominco, and Royal Oak — address the long-term problem, some mine owners threatened to shut down operations. For settler-rooted workers, this was a frightening prospect. Indigenous residents were less concerned about job loss, given that so few of them were employed by the mines. Their larger concern was survival.

The fight against arsenic pollution got an early boost when CBC Radio’s As It Happens blew the lid off Giant’s continued stalling in January 1975. The show also pointed to the governmental red tape that had been steadily frustrating efforts to pin down a solution. Two years later, a Globe and Mail headline declared, “Ottawa Hides the Poison.” David Suzuki joined the fray along with Georges Erasmus, then the president of the Northwest Territories chapter of the National Indian Brotherhood.

Even more public disapproval came during a long strike and lockout in spring 1992. Royal Oak’s CEO Peggy Witte hired replacement workers and engaged the private Pinkerton security agency. Acrimony and physical clashes culminated in the deaths of nine replacement workers in an explosion. A unionized miner eventually pleaded guilty to the murders.

Other travesties of the mining world have been exposed, but the poisoning of Rainbow Valley had an added dimension of carelessness — one tinged with racism. As the NIB sarcastically stated, “Only Indian people are in danger of arsenic poisoning, so there is not really any problem.”

The mines are now closed, but after decades of arsenic accumulation in their abandoned shafts, threats linger. Today environmentalists and concerned Yellowknifers are advocating for the permanent containment of the poison. Government action is needed, as mining companies too often fail to clean up their mess. Witness the hundreds of dead oil wells that remain a blight on the Alberta landscape.

More than 100 years ago, gold seekers rushed to the Klondike in hopes of striking it rich. Since then, the North has been ravaged by legions of profiteers, exploiters, and those who enable them. Along the way, there have been plenty of victims. Still, there is hope. No one expects another hero like Thomas Berger, who flew to the rescue in the 1970s. Yet lesser-known individuals continue to practise a “creative activism,” and a remediation project is now seeking ways to mitigate the underground contamination — enough, many have said, “to fatally poison every human being on the planet four times.”

Ron Verzuh is a historian and documentary filmmaker based in Victoria. He previously lived in Yellowknife and worked for the News of the North in 1973.