It is impossible to understand Peter C. Newman’s When the Gods Changed: The Death of Liberal Canada without knowing the context that surrounds its writing. The original vision was to chronicle the ascension of Michael Ignatieff to the prime minister’s office. In the same way he documented other larger-than-life Canadians, Newman would record Ignatieff’s rise to power as an ordained outsider, through the kind of long interviews that are allowed when subjects let flattery override good sense.

But history had other plans. As Newman notes: “the election results unraveled my narrative arc and turned it into skywriting, scattered by the breeze.” Newman was not dealt the hand he expected and, to his credit, he lays that fact out for his readers.

The interesting but somewhat awkward result is that When the Gods Changed is not a single book, but rather two distinct books, building to a dramatic crescendo: that the Liberal Party of Canada is dead.

The first book is strictly about Michael Ignatieff: who he is, the forces that shaped him and how he ultimately rose to the top of the Liberals. The second is about the history of the Liberal Party: how it rose to become Canada’s dominant political party of the 20th century. At the end—literally the last chapter—Newman attempts to weave these two books together, to posit that the Liberal Party is now spent as a political force in Canada.

Book One: Ignatieff’s Political Career

While the planned trajectory of the book was ultimately derailed, Newman tells a succinct story of Ignatieff’s political life, from his recruitment from Harvard University by Ian Davey, Dan Brock and Alfred Apps through to his election loss in 2011. His pop-psychologizing is sometimes distracting (he literally enlists a psychologist to help him “analyze Ignatieff’s psyche”). But Newman successfully identifies a central problem of Ignatieff’s tenure missing from most accounts: in order to survive as leader of the Liberals, a once-insurgent leadership candidate turned inward to seek support from the party establishment and, in so doing, appeared the type of Liberal Canadians had just rejected.

Norman Yeung

From the beginning, Ignatieff was surrounded by confidants who saw themselves as insurgents. Davey, Brock and Apps had supported John Manley’s short campaign against a Paul Martin leadership coronation. As Davey told Newman at the time,

our aim is to change the political culture of how public policy is developed in this country. What’s happened of late was that we didn’t stand for anything except winning elections. Too many people in the Liberal party were basically in it to make a living, becoming lobbyists who peddled their influence. That was the culture that had to be changed.

A key manifestation of this, and one in which both the authors of this article were engaged, was the building of a virtual think tank. This involved recruiting a wide network of policy volunteers. The group was based around the world; most had never engaged in politics before; they were from a diverse range of ideological positions; many participated in confidence; and all wanted to be a part of building something new. This group was clustered into policy categories and provided regular briefings to Ignatieff. It was a genuine innovation in campaign organization and opened a door for non-lifelong Liberals to participate meaningfully in the political process. As Newman rightly depicts, “Ignatieff supporters weren’t necessarily Liberals; many were activists who wanted to be involved with something new and exciting … most of them saying, ‘I’m not interested in common politics, but this is a guy I’m interested in and I want to help.’” Such was certainly the case in the policy camp.

But the model was not resilient. As Newman recounts, once Ignatieff ultimately captured the leadership of the party after the 2008 general election, the daily pressures of leading the Official Opposition led to a very different type of politics: a politics that was, perhaps rightly, focused on the day-to-day demands of partisan Ottawa but that lost sight of the greater project—challenging and renewing the structure, policy and culture of the party.

This reversal was complete when Ian Davey and the half-dozen others remaining from the original team were unceremoniously replaced by Liberals from past governments. One result was the disintegration of the policy network, and the much-lauded 2010 Liberal Party “thinkers’ conference” proved more echo chamber than innovation. These changes were portrayed in the press as a call to the benches for experience. Newman argues that what they actually represented was a final turn inward by the party, and an acknowledgement that in order to become prime minister Ignatieff would bet on the past successes of a 20th-century party over a reform project that had never really gotten off the ground.

Book Two: The 20th-Century Liberal Party

The second book embedded within When the Gods Changed covers the history of the rise of the 20th-century Liberal Party. Designed to stand in opposition to the decline during Ignatieff’s tenure, this section must have been the least challenging part for Newman to write. That is both its weakness and its strength.

Its strength derives from Newman’s grasp of Canada’s political history, so much so that this narrative reads as much like a personal history for Newman as a political history for the rest of us. There are few observers who have sat down for extended periods with St. Laurent, Diefenbaker, Pearson, Trudeau and Mulroney, enjoyed their confidence and written books about many of them. But more than an observer, Newman was a friend. Here was a man who hosted Trudeau and his girlfriend for dinner on a regular basis and can recount how a hospital-bound Bryce Mackasey—who suffered a heart attack on the floor of the 1968 Liberal convention—begged him to “tell Trudeau I want Labour!” This is a history effortlessly pulled from deep, story-filled pockets.

It makes for a fun and fascinating read, especially for political geeks.

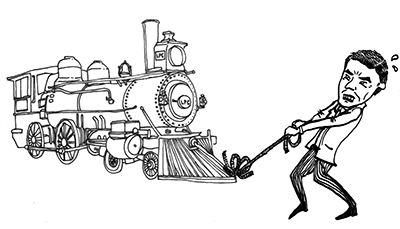

However, it is also the source of the narrative’s weakness. Since, mid-writing, the book transformed from being about Ignatieff’s rise to the Liberal Party’s demise, it is hard not to feel as if this narrative is a graft. The Ignatieff storyline reads like a strenuous wrestling match: filled with struggles, second guessing, hopes and concerns. You can feel Newman trying to understand who Ignatieff is and what his story means. In contrast, the history of the party feels like a gentle stroll on a familiar path. The intensity is simply not there, and one senses that Newman could have written it in his sleep.

There is, in addition, a deeper challenge to Newman’s history of the Liberals. His focus on personalities enables him to cite the evidence of hubris and a culture of entitlement within the party, but does not lend itself to understanding how those problems came about or, more importantly, why they are so difficult to address. Alas, all successful political parties suffer from hubris. This in and of itself is not particularly enlightening. There is a rich literature of organizational and business management books that focuses exclusively on the problems of renewal. And, while almost all discuss the role of leaders and culture, they often also talk of deeper underlying problems.

In the case of the Liberals there is no doubt that hubris was crippling, but it fails to explain why the party was, in the past, able to overcome it and integrate new ideas to renew itself, whereas this time around it is experiencing significantly more trouble. This is doubly the case if, as Newman argues, Ignatieff was merely the problem’s catalyst, and not ultimately responsible. Something else is at work.

The Death of the Liberal Party?

Newman tries to bring his two very different books together in the final chapter, making a case that the party is broken beyond repair. The federal Liberals will die, says Newman, because they no longer have a regional power base, and new party fundraising laws will make it hard for them to pull in sufficient money for effective campaigning. These points are both true, but they are far better explanations for why the party may not re-emerge than why it declined.

More importantly, Newman seems intent on forcing the Liberal Party’s troubles into a narrative of psychological disrepair. And it is certainly true that the cocksure certainty of governance among party faithful takes time to dissipate. But an author who spends years looking at the world through the eyes of his or her subjects can fall victim to a type of biographical determinism—a view of history that places far too much weight on the actions of those being written about. Herein lies the central problem with this book. Newman wants to see the recent decline of the Liberal Party exclusively through the thoughts and actions of his subjects, Michael Ignatieff and a few “kingmakers” around him.

This reflects a flaw in Newman’s character-driven writing style. For example, Brad Davis, who built Ignatieff’s virtual think tank but tragically passed away before Ignatieff won the leadership, does not figure prominently. Nor, therefore, does the innovative behind-the-scenes campaign that Davis led. On the other hand, Newman pays disproportionate attention to a seemingly impressive but relatively unknown candidate named Dan Veniez, running in a riding where he maintained a residence. Consequently, one is left feeling that figures are given historical prominence based not on the nature of their influence and role, but on their exposure to Newman.

The Liberal Party’s real baggage is not psychological; it is institutional. Over the course of a century, the party built a series of social institutions designed for an industrial world. As the information age has fundamentally changed citizens’ challenges and expectations, Liberals have been left defending the existence of institutions, some now broken or in disrepair, over the progressive values they were originally intended to promote.

Health care is likely the best example. The Liberal Party regularly talks about being the saviour and protector of health care, and yet the system’s costs continue to rise. Canadians are increasingly nervous about its sustainability, and yet the Liberals (and the NDP) fail to acknowledge the challenges or propose any solutions beyond more funding. Indeed, even talking about healthcare reform is considered “anti-Canadian.”

The duelling interviews Newman quotes with Davey—the insurgent reformer—and Peter Donolo—the experienced Liberal staffer who replaced Davey in Ignatieff’s office—are telling. Both address the challenge the party faces in getting elected, but neither articulate why the party has been so marginalized. Donolo sees a party that ran a perfect campaign in 2011, defeated because the public does not care about policy and is easily duped by Conservative tricks. Davey argues that the party’s culture is broken, consumed by “professionals” and “players wielding power.”

But while these explanations may appear contradictory, they are not. If the Liberal campaign was flawless, then it truly means the party’s message did not connect. And it will likely be difficult for the party to find a message that connects so long as the same ideas and perspectives are driving decisions. Thus, as Newman himself states in a passage that points to the heart of the problem, the party will need to go further, addressing not just its operation and culture, but its actual relevance to contemporary Canada:

The new guard who brought Ignatieff into the party were trying to fight that status quo. They believed that somebody who had lived by ideas, wrote well and had spent his entire career thinking about politics should have been a natural source of renewal … His problem, once he became leader, was that voters had no idea—not a clue—what the disintegrating Liberal Party of Canada actually stood for, except as a vehicle for gaining power, by representing the elusive “middle”. The party needed much more than message tweaks and incremental reforms.

While Davey is dismissive of his efforts to reform the party, the reality is that both he and Ignatieff brought a wide range of new people, energy and ideas into the Liberal fold. But these people will need to move beyond a rearticulation of 20th-century ideas, presented through a modernized campaign. They will need to rethink the place of liberal politics in Canadian society. Newman is right: a 21st-century Liberal party may not look anything like the 20th-century juggernaut. But that would be a good thing.

David Eaves is an adjunct professor at the Centre for Digital Media and is frequently asked to write and speak on public policy, open innovation and politics.

Taylor Owen is a professor of digital media and global affairs at the University of British Columbia, a senior fellow at the Columbia Journalism School and author of Disruptive Power: The Crisis of the State in the Digital Age.