As the world inches closer to the 2015 target of the Millennium Development Goals, development

practitioners across the globe are reflecting on the progress made against the MDGs as well as considering what the post-2015 global development agenda could look like. Which institutions, interventions, frameworks and partnerships have had the most success in alleviating poverty and are best placed to advance development? What are the transformative shifts to create a world free of poverty and achieve prosperity, equity, freedom, dignity and peace? Whose political and moral leadership can the world rely on to carry a new development agenda forward?

The world we want is not just the fodder of politicians, development bureaucrats, non-governmental organizers and grassroots mobilizers, but also a subject deliberated over centuries in great detail by the papacy. The Vatican perspective is particularly interesting these days, with the arrival of the current pope, Francis, who has spoken very openly about the transformation of the church and the negative whims of the capitalist economy, and who is urging a strong moral direction to embrace the poor. In Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”), Pope Francis wrote, “I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security.” This transformative spirit emphasizing care for the poor, tenderness, mercy and compassion—coming from Time Magazine’s 2013 Person of the Year—has captured the imagination of publics everywhere. And of development professionals such as myself, in particular, because a well-known, prosperous institution with fresh, charismatic leadership and a strong focus on the poor could present a unique opportunity for making a serious dent in poverty alleviation and human suffering across the developing world.

For this reason, Robert Calderisi’s new book, Earthly Mission: The Catholic Church and World Development, is very timely. With a focus on the role of the Catholic church in international development over the last 60 years, the book aims to provide an assessment of whether, and what, progress has been achieved to date. For readers with a general interest in religion or development, the book is also an introduction to the role of a religious institution (the Catholic church) in the alleviation of human suffering, and the distinctive opportunities and challenges that come with that mission. Earthly Mission is based on Calderisi’s own research and interviews with more than 150 people in 20 countries.

Himself a Catholic and former World Bank professional, Calderisi could not have picked a more captivating and contentious intersection of human activity to examine. Both the Catholic church and development are controversial subjects in their own right, requiring deep and delicate handling, and it is to the author’s credit that he decided to straddle both worlds in his book. Perhaps not surprisingly, the intersection of the church and development brings out the best—and the worst—in both.

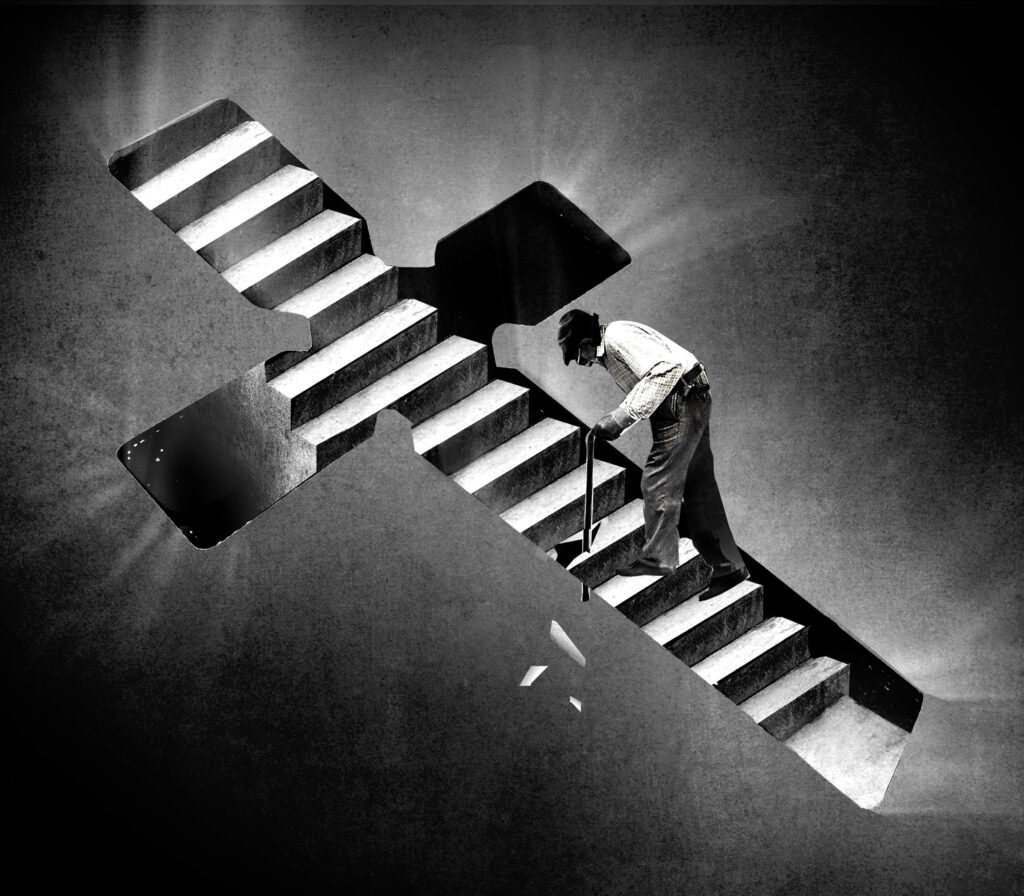

Anthony Tremmaglia

Calderisi’s overall conclusion is that the Catholic church’s role has had positive results in alleviating global poverty and advancing development. He states clearly that “while it is difficult to prove by conventional methods, the circumstantial evidence is overwhelming.” Furthermore, if more implicitly, he believes that the role of the Catholic church cannot be ignored, because of its vast experience to date, and its “special” opportunities and influence, at least compared to other Christian confessions, that make it stand out in the development arena. These include its size, global reach, resources, social teaching and structure, and, in Calderisi’s view, the idea that the pope speaks for almost a third of humanity.

Calderisi also concludes that the role of the Catholic church in development is at its best when Catholic development efforts build positively on local experience and are delinked from the positions and internal conflicts of Rome. This is because power struggles and preoccupation with dogma within the Vatican often do not dovetail with the practical or commonsense realities of many dedicated Catholics involved in development. When describing the experience of French nuns in Niamey in Niger, demonstrating to about 200 women how to put a condom on a wooden phallus and explaining how to discretely put condoms on with their mouths should their husbands be inclined to reject them, Calderisi notes the nuns’ sense of service and purpose that focuses on effective development work without taking away from their dedication to Catholicism. “Oh, you mean the Pope?” he quotes one of them saying with regard to the Church’s anti-contraception dogma. “We respect him. In fact, we love him. But [pointing to the women] this is the reality. If we don’t do this, a large number of them will die.”

Thus Calderisi notes, the Church is not about to close its 140,000 schools, 18,000 clinics, and 5,500 hospitals. It still has work to do in its 37,000 centers of informal education, 16,000 homes for the elderly and handicapped, 12,000 nurseries, 10,000 orphanages, and 500 leprosaria. Church people in those institutions are still largely motivated by their faith and their sense of service rather than the passing preoccupations of theologians.

Furthermore, with its focus on charity, education, health and its often reliable and far-reaching development networks across Africa, Asia and Latin America (although of varying geographical proportions), he observes that the church is often a major player in developing countries. In specific instances that he cites, Catholic leaders—such as Pere Negre who organized a national hunger strike in Bolivia to recover the bodies of students who had been shot in the back of the head by the military government— exemplify human courage of God-like magnitude. In political shifts, Catholics have helped to end civil war and facilitated peace in countries such as Mozambique. These are but a few examples of the service to humanity and broader development influence and impact of the Catholic church.

As a development professional, I have found that my experience with an HIV-positive orphans program run by Camillians (Clerics Regular, Ministers to the Sick) near Bangalore, India, was most inspiring. It exemplified the collaborative spirit, partnership and robust result expected of progressive development interventions.

That’s the good news. When it comes to the not-so-good news about the church’s role in development, Calderisi— although he makes an honest attempt to broach a very challenging subject—often stumbles in terms of his analysis and conclusions. Here are some of the areas I found most troubling.

Given that this is supposedly a book “for a general reader with an interest in international affairs and an open mind about religion,” why focus exclusively on the Catholic church? No factual comparisons are made with other Christian confessions in terms of development aid, or with other world religions. Judaism’s practice of tzedakah or Islam’s practice of zakat/sadaqah are ignored, for instance. Research has shown that Jewish families in America are more likely than their Christian counterparts to contribute to charities; Islam’s zakat and sadaqah are estimated to generate between $200 billion and $1 trillion annually for charitable purposes (at least 15 times more than global humanitarian aid contributions in 2011). ((See “Analysis: A Faith-Based Aid Revolution in the Muslim World?” in IRIN, published on June 1, 2012. IRIN is published by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.))

Putting even a few comparative figures into his analysis could have helped strengthen Calderisi’s argument of Catholicism’s uniqueness in development more factually, providing more reason for readers to pay attention to his book.

Calderisi’s sometimes unabridged comments on the positive aspects of Christianity’s impact in global development indicate historical neglect. For instance, he notes that “there is little controversy that Christianity as a whole nurtured the emergence of capitalism and that other belief systems did not.” This could be true but it cannot explain the development experiences of other cultures and their economic regimes, and the relevance of this fact to his book’s focus on the experience of the Catholic church in development over the last 60 years. Many centuries of prosperity and development have unfolded under non-Christian experiments, such as the Han dynasty in China (Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religions), the Ottoman and Islamic empires, the Khmer Empire, the Silla Empire, and so on. The lack of appropriate universal contextualization of Catholicism and development makes Calderisi appear less open minded than his own expectation of his readers.

A third and crucial point. Development, despite its technocratic approach to poverty alleviation, is a political activity. By virtue of its stature, finances, moral positions and its occasionally treacherous silence, the Catholic church—in my view but not in Calderisi’s—is also a highly political entity. Here are a few snapshots from the book: the complicity of bishops with Argentinian army generals in human rights violations; Vatican diplomats hobnobbing with the apartheid government of South Africa to maintain good relations; playing first (or second)fiddle to European colonizers in the destruction of indigenous family and cultural institutions in the name of conversion, modernization and westernization (an item Canadians will doubtless recognize in relation to the residential schools); and the prohibition against modern contraception and safe abortions—critical from a development perspective to the empowerment of poor mothers, women and adolescent girls—which ends up denying right of life, opportunity and potentially a life free from infirmity.

The Catholic church’s development activities in Africa, Asia and Latin America are therefore as degrading as they are inspiring. At one level the circumstantial evidence Calderisi presents shows great progress; at another, stacking up the violence and politicking suggests regression.

With such a complex and contradictory picture of the church’s development impact, the need for standards or indicators to measure that impact is critical. But this is where Calderisi’s analysis displays its greatest weakness. Readers are, rather shakily, forced to rely on the author’s own experiences and reading of the situation, which is not helpful in a book examining such controversial topics. Data on development impact could have backed up Calderisi’s conclusion by demonstrating formal attribution, an attribution that would have also helped him tie Catholic experiences in development to advancing global development frameworks such as the MDGs: How many lives saved or people lifted from poverty were due to interventions by the Catholic church, or Catholic NGOs such as Caritas Internationalis? How did this impact advance (or lessen) the achievement of one, several or all the MDGs, or the development frameworks of previous decades? No such questions are asked and answered here.

Moreover, while Calderisi speaks of development theory in broad strokes, he is not able to demonstrate how the interventions by Catholic development actors align or are in sync with current best practices or innovative development thinking. Calderisi highlights, for instance, that the Catholic church’s view of development bears a close resemblance to Amartya Sen’s influential human capabilities approach, but that is about where Calderisi stops. Similarly, his analysis neglects the perspective of the people the Catholic church serves to help—the very poor who are affected by the interventions themselves. Including a few struggling barrio residents on his interview list would have given less of an ivory tower feel to his book and a more humanizing and participatory development focus.

Finally, nowhere does Calderisi allude to how Catholicism’s charitable and development interventions are sustainable in the long term. The greatest challenge (and opportunity) in development is to ensure that the impact of intervention lasts beyond the intervention itself. How do the interventions driven by the Catholic church support long-term country ownership for development, help to get the Catholic church (as a development actor) successfully out of business (a goal most development actors should aspire to) and, importantly, strengthen the poor’s ability to help themselves lead a life they themselves have reason to value? Calderisi is silent on such questions.

Given the strain on aid budgets, the unfinished business in eliminating global poverty and constant new challenges, the development enterprise continues to be in need of the best knowledge, skills, time and effective actors it can marshal.

Calderisi believes that the Catholic church must be part of the solution of alleviating mass global poverty. I believe it could be, but Calderisi’s analysis has convinced me that more needs to be done to demonstrate the church’s effectiveness and added value. Furthermore, while we cannot expect a full reversal of the Catholic church’s major positions (such as against contraception or abortion) or of self-interested politicking that hurts or reverses development efforts (as in treating poor patients differently because they are not Christians), there needs to be a more practical approach in the Catholic church, and thus more flexibility and nuance on its own positions and actions— for example, if Pope Francis is serious, putting the poor ahead of the church itself. This also demands going far beyond the Catholic church’s symbolic acts of atonement to embrace, contribute to and innovate global development standards and interventions.

Related Letters and Responses

Robert Calderisi