The past several decades have not been auspicious for the Canadian labour movement. Only 25 years ago, unions represented 38 percent of the Canadian workforce and were at the zenith of their influence and visibility. Union leaders met regularly with prime ministers and premiers, and most major newspapers and broadcasters had a full-time labour-beat reporter. Bob White and the auto workers captured the attention of many Canadians by breaking away from their American parent union in 1985 and then leading an inspired campaign against the Mulroney government’s proposed free trade agreement with the United States. Through this period, governments of all stripes in Ottawa and the provinces enacted worker-friendly legislation that promoted workplace health and safety, employment equity, pay equity and union organizing. By the early 1990s, the New Democratic Party—the political ally of the labour movement—was in power in three Canadian provinces, including Ontario, and held 43 seats in Parliament. This was not yet the New Jerusalem, but it did not seem so far away.

Fast forward to 2011, and the labour movement is bleeding. Unions now represent less than 30 percent of the Canadian workforce, their lowest numbers in 50 years. Labour’s share of Canada’s gross domestic product hovers at 53 percent, down from 58 percent in 1991, illustrating its steady loss of economic bargaining power. Unions rarely strike now—labour disputes leading to lost time at work amounted to 0.42 percent of annual working time in 1976, and only 0.01 percent by 2006—but their waning political strength means that they are more easily punished today when they do walk out. In March, the Ontario legislature withdrew the right of Toronto’s transit workers to strike; Toronto’s new mayor is about to privatize the collection of much of the city’s garbage after a rancorous strike by municipal workers in 2009; and the Quebec legislature forced its Crown prosecutors and lawyers back to work following a two-week strike in February that had brought the province’s criminal justice system to a halt. All this is happening as more Canadians are becoming just-in-time workers: the percentage of employees in the labour force who are working in casual, part-time and temporary jobs has doubled in the past 30 years. Most of these just-in-time workers are more vulnerable than employees in standard relationships, but their contingent connection to the workplace makes them much harder to unionize.

Should we lament the decline of unions in Canada? A common complaint in editorial pages and by the new conservative movement is that unions are political dinosaurs that stifle innovation in the new economy and drain public finances to pay for generous pension and benefit plans. More thoughtful and informed observers, such as Paul Krugman and the International Labour Organization, point to the social benefits of strong labour laws and a vibrant union movement ((See Paul Krugman’s The Conscience of a Liberal (W.W. Norton, 2007) and the International Labour Organization’s World of Work Report 2008: Income Inequalities in the Age of Financial Globalization (ILO, 2008).)). Besides being the single most effective institution for ensuring fairness at work, they argue, the biggest macro-social benefit of unions has been their encouragement of economic equality by expanding the middle class and pushing for a greater share of public spending to be directed toward education, health and social programs. More equal societies frequently produce better health and quality-of-life results ((See, for example, The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett (Penguin, 2009).)).

In Canada, our levels of economic inequality shrank between the mid 1940s and the mid 1980s as the labour movement grew, and they have steadily widened since 1985 as unionization has declined. The provinces with the highest levels of unionization—Newfoundland, Quebec, British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan—are also among the provinces with the lowest rates of economic inequality.

A new book on the Canadian workplace—Work on Trial: Canadian Labour Law Struggles, edited by Judy Fudge and Eric Tucker—provides an engaging and accessible account of various labour battles in the courts over the past 85 years involving human rights, employment fairness and union recognition. Read against the landscape of today’s declining strength of Canadian unions, the essays in the book remind us of the centrality of work in our lives and the many forms that the struggle for individual dignity and fairness has taken.

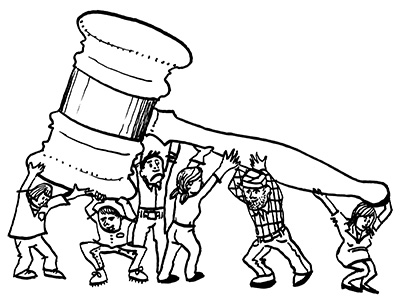

Norman Yeung

Normally, a book of essays by academics on unions and the law would capture the interest of only a small and select audience. This book deserves a wide readership. Lucidly written and astutely argued for the most part, the articles in this collection tell the individual stories of employees in a range of occupations—female forest firefighters, dock workers, printing salesmen, pregnant flight attendants, offshore oil workers and hotel cleaning staff—who all turned to the law as a last resort and went on to win seminal workplace benefits and historic employment and human rights. These essays, written as social histories of these legal cases, will appeal to anyone interested in the human stories of those ordinary Canadians who found themselves fighting, often unexpectedly, for fairness in the workplace.

Like oaks and acorns, landmark human rights rulings invariably start from innocuous beginnings.

In the early 1990s, Tawney Meiorin was working as a forest firefighter for the Government of British Columbia’s Forest Service at various fire suppression camps in the province’s interior. The job demanded aerobic fitness, nerves of steel and a tolerance for bone-wearying work and gruelling hours. At the time, firefighting in the B.C. forests was distinctly a man’s world: fewer than 10 percent of the forest firefighters were women. Throughout her five summers as a firefighter, Meiorin had received good performance evaluations from her employer and, for all of its dangers and tribulations, she loved the work.

In 1994, the B.C. Forest Service stipulated that its 800 firefighters had to successfully complete a new aerobic standard test as a condition of re–employment. This new fitness test had been designed by kinesiologists at the University of Victoria in the aftermath of a coroner’s inquest into the death of a B.C. logger during a forest fire. Meiorin successfully passed the first several parts of the aerobic test, but she failed the time-trial running component. She was required to complete a two-and-a-half kilometre run in less than 11 minutes, and her fastest effort after three attempts was eight seconds over the limit. As a consequence, Meiorin lost her job, and her union—the British Columbia Government and Service Employees’ Union (BCGEU)—challenged the termination through the grievance process. Arguing that the new fitness test discriminated against women, Meiorin initially won her case in front of a labour arbitrator, but lost on judicial review before the British Columbia Court of Appeal.

When Meiorin’s appeal reached the Supreme Court of Canada in 1999, she and her union lawyers faced two daunting challenges. First, they had to convince the judges that the prevailing legal test on accommodating human rights claims at work was clumsy and overly complex. And second, the Supreme Court had to be persuaded that the new fitness test implemented by the B.C. Forest Service was fatally flawed because it did not properly account for the lower aerobic capacity of women. In a path-breaking judgement, Meiorin and the BCGEU won on both counts.

These were both significant accomplishments. In 1990, the Supreme Court of Canada had created a sophisticated legal test on workplace anti–discrimination claims, but, as the Court acknowledged in Tawney Meiorin’s case, this test had proven to be complicated and challenging to use. By clarifying the legal test and strengthening the obligation on employers to accommodate their workers, the Meiorin ruling has become the most influential workplace human rights decision over the past 20 years. Many thousands of Canadian employees—unionized and non-unionized—have since acquired beneficial accommodations at work on the grounds of disability, religious beliefs and family status, directly thanks to Tawney Meiorin’s win.

For women workers in Canada, the Meiorin case was a major sex equality victory. In its judgement, the Supreme Court accepted that the B.C. Forest Services had developed the 1994 aerobics fitness test in good faith to protect the safety of its firefighters. But the Court went on to find that the Forest Service had not properly included experienced women firefighters in the original design of the test. While two thirds of the men who took the 1994 test passed, only one third of the women were successful. When the onus shifted to the B.C. Forest Services to prove that a differently designed fitness standard—which would enable more women to succeed—would compromise safety or efficiency in fighting forest fires, it was unable to do so. With the Meiorin ruling, women acquired a potent legal tool to challenge prevailing employment rules—such as strength capacity codes, lifting standards and height requirements—that have long been glass barriers to non-traditional jobs.

Why did Tawney Meiorin’s case succeed when other human rights challenges to unfair work practices had failed? In their incisive essay on the case, Judy Fudge and Hester Lessard point to the critical factors that shaped this victory. Meiorin was a credible and charismatic litigant who inspired others to fight with her. The experts who designed the 1994 fitness test for the B.C. government placed too much reliance on physiology and not enough on the ways that workers interact with their employment environments. The generation of women who won workplace battles on equality rights in the 1970s and ’80s created the political and legal foundations for their daughters to challenge the more nuanced forms of gender discrimination at work. And, most decisively, Meiorin’s union provided her with indispensible financial, political and legal support, even though her case was unpopular with many of the union’s male forest firefighters. More than we may acknowledge, unions are often capable of doing the right thing.

Law, like history, is often a pageant of incremental accomplishments and defeats that lays the ground for the next step forward. Tawney Meiorin’s union would have never had the financial capacity to launch her fight if the 1945 auto workers strike against the Ford Motor Company in Windsor, Ontario, had not produced the famous Rand formula on union dues. The Ford strike, which lasted for 99 days and involved more than 11,000 workers, was fought over the issue of compulsory union membership and the deduction of union dues from all employees. At one point in the strike, auto workers sequestered about 1,000 cars and buses from the streets of Windsor and parked the vehicles in dense rows around the Ford operations, completely closing off the plant.

Eventually, Justice Ivan Rand of the Supreme Court of Canada was appointed by Mackenzie King’s government to arbitrate the strike’s contentious issues. To settle the conflict, he devised a creative solution that ruled out compulsory union membership, but did require all employees, whether union members or not, to pay dues to the union. “The employees as a whole,” Rand wrote, “become the beneficiaries of union action, and I doubt if any circumstance provokes more resentment in a plant than this sharing of the fruits of unionist work and courage by the non-member.”

Sixty-five years later, the Rand formula remains a centrepiece of Canadian labour relations. It is found in most collective agreements across the country, and it survived a bitter 1991 Charter of Rights and Freedoms challenge at the Supreme Court of Canada. Although all the unions in Canada put together would not match the financial size of any one of the country’s 150 largest corporations, the Rand formula does provide unions with stable funding to exercise a modicum of political and economic clout in their encounters with companies and governments. Yet according to the labour arbitrator and historian William Kaplan, the formula has also made unions tamer. In his essay, Kaplan argues that Rand’s innovation put the brakes on shopfloor militancy by incorporating unions into a regime of industrial legality that imposes a complex set of rights and responsibilities. The consequence today is that, despite the public perception, unions spend far more time battling for their rights in legal forums and at bargaining tables than they do on picket lines.

Another workplace battle that seems distant today, but was a hotly debated issue only 35 years ago, is the right of female flight attendants to “fly pregnant.” Up until the 1970s, maternity leaves were considered a privilege, not a right, and women would routinely be forced to quit work once they became pregnant. In the airline industry, the union representing fight attendants had just successfully challenged the prevailing rule that barred married and divorced women from employment. Again using legal forums, the union now fought the airline requirement that pregnant flight attendants take a mandatory maternity leave once they were four months pregnant. Despite losing all of its court cases on the issue, the flight attendants’ union ultimately succeeded at the bargaining table and through amendments in 1985 to the Canadian Human Rights Act and the Canada Labour Code that gave all working women in the federal sector the right to work later into their pregnancy. Historian Joan Sangster attributes the union’s ultimate victory to its use of equality arguments—pregnancy discrimination is a form of sex discrimination—that challenged traditional ideas about the capabilities of expectant working mothers and paved the way for much better maternity leave provisions in today’s workplace. Tawney Meiorin’s victory several decades later stood on the shoulders of the pregnant flight attendants.

Other struggles for fairness and rights in the courts are vividly chronicled in Work on Trial. A highly successfully, if irascible, printing salesman in Winnipeg who was summarily fired because of personality differences with his manager and then fell into a lengthy depression won a half-baked victory at the Supreme Court of Canada in 1997. The ruling left him with a modest settlement, but established a mandatory obligation on employers to treat their employees with dignity when ending an employment relationship.

A strike in 1961 by service workers at the Royal York Hotel in downtown Toronto over bread-and-butter concerns regarding better wages and benefits ended up in the Supreme Court of Canada, and created the fundamental legal principle that employees cannot be fired for exercising their legal right to strike. And a modest attempt by a determined supermarket clerk to picket on the sidewalk of a shopping centre against her employer wound up testing the perennial legal conflict between property rights and freedom of expression in the nation’s highest court in 1975. The clerk and her union lost their case, as the Supreme Court ruled that trespassing laws trumped any claim to peacefully carry a picket sign on private property. However, this defeat would become an eventual victory, as unions and picketers would later employ the Charter of Rights in the courts to establish the importance of free expression in a democratic society, including the right to protest in shopping centres where the owner had welcomed the public to enter its private property.

The influence of unions in Canada is waning, but they are far from the enfeebled state that the American labour movement now finds itself in. The growing appetite by Republican law makers in Wisconsin, Ohio, Maine, New Jersey, Texas and other states to roll back the statutory and contractual rights of public sector unions would not likely be possible in Canada, partly because the Charter of Rights and Freedoms would almost certainly forbid the wholesale stripping of labour rights. But this liberal reading of our Charter has only happened because unions have begun to persuade the Canadian courts, after many unsuccessful attempts, that labour rights are human rights and therefore worth protecting. Through its many fascinating stories, Work on Trial reminds us that laws that establish rights or address social concerns do not emerge fully formed from enlightened legislators and judges, but invariably arise first from the tiny struggles of individuals who join together for a broader purpose.

Michael Lynk is the associate dean of the Faculty of Law at the University of Western Ontario. He is also a labour arbitrator. Before donning his academic robes, he worked for a decade as a labour lawyer in private practice and on the staff of several national unions in Ottawa and Toronto.