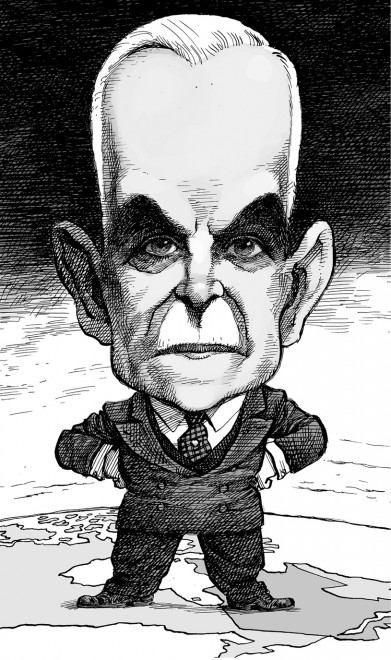

Louis St‑Laurent is almost forgotten by Canadians, and it is unlikely there will ever be a new biography: unfortunately (and inexplicably), his papers at Library and Archives Canada are scanty, devoid of interest. There is hardly anyone left to interview — the sole exception being Paul Hellyer, who entered the twelfth prime minister’s cabinet as associate minister of national defence two months before John Diefenbaker won power in 1957. There are a couple of good books on him: a biography by Dale Thomson, who worked in his office, and another by J. W. Pickersgill, his closest aide and former clerk of the Privy Council. But both men were Liberals, and neither had anything bad to say about a leader they respected greatly.

Perhaps there are few negative things anyone can say about a man whose primary characteristics were intelligence and integrity. St‑Laurent was born in Compton, Quebec, in February 1882. His father was a francophone storekeeper and his mother the child of Irish immigrants. He attended classical college and then law school at Université Laval, and was offered — but declined — a Rhodes Scholarship in 1905. Instead, he began a successful career representing corporate interests as well as Jews who wanted a voice on Montreal’s Protestant Board of School Commissioners (there he did not succeed). During the Great Depression, he was legal counsel for the Rowell-Sirois Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations, and in late 1941, when Mackenzie King’s Quebec lieutenant, Ernest Lapointe, died, the prime minister asked him to become justice minister. St‑Laurent accepted as a matter of wartime duty, and he soon became King’s right-hand man. In 1946, King tired of serving as his own foreign minister and stepped down as secretary of state for external affairs, and St‑Laurent assumed the role. On King’s retirement, in 1948, he was chosen as Liberal leader and prime minister by a party convention.

A giant of intelligence and integrity.

David Parkins

To some surprise, the new chief proved a very successful campaigner: his “Uncle Louis” persona and his ability to relate to voters and their children were impressive. He swept the nation in the 1949 election, capturing 191 seats and 49.1 percent of the popular vote; in 1953, the Liberals won 169 seats and 48.4 percent of the vote. Even in 1957, when St‑Laurent was old, weary, and gripped by depressive episodes, he won 105 seats and 40.5 percent of the vote, while Diefenbaker’s Progressive Conservatives took 112 seats and 38.5 percent of votes cast. St‑Laurent might have tried to win support from the CCF and Social Credit to stay in power, but he resigned from office and very soon from the party leadership.

The St‑Laurent government’s record was impressive. Pickersgill’s famous line was that St‑Laurent made governing look so easy that Canadians believed anyone could do it — and that was why they elected Diefenbaker. St‑Laurent ran his cabinet, leaving no doubt that he was

in charge, while giving his strong ministers — including C. D. Howe, the “minister of everything”— their head. As Robert Bothwell notes in this new collection, he had a “quick, sharp mind and a decisive temperament.” He brought Newfoundland and Labrador into Canada and ended appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in the U.K. He had generally good relations with the provinces; for most of his tenure, even Maurice Duplessis, the premier of Quebec, was quiescent.

In 1954, St‑Laurent was the first Canadian leader to undertake a world tour — an event that even the opposition cheered. And yet that long trip in a slow and noisy RCAF aircraft sapped his energy, so much so that he seems not to have recovered fully, and his last years in office were far from his best. The Pipeline Debate, which Howe directed in spring 1956, earned his government a reputation for arrogance. Then St‑Laurent and his foreign minister, Lester Pearson, broke with Britain and France over the Suez Crisis in late 1956, a move that sharply divided Canada and led to much criticism of Ottawa for simultaneously supporting the position of the United States and abandoning Canada’s mother countries. Combined, these two issues likely led to the defeat of 1957.

I met Louis St‑Laurent once. I was researching a book about the Mackenzie King government during the Second World War, and Jack Pickersgill arranged for me to interview the ninety-year-old at his home in Quebec City. It was November 1972, and St‑Laurent was quite frail. It showed during the hour I was with him: he confused events from the First and Second World Wars, and he seemed unable to focus for more than a few minutes. I was horrified, feeling that I had intruded on a sick man; indeed, he died eight months later.

Pickersgill sat in on the interview and was very upset as well. As we left, he was close to weeping at what was happening to the man he thought of as a great prime minister and close friend. Pickersgill had worked with St‑Laurent at the height of his powers, and he knew that the man was beset by bouts of depression, some prolonged, from the early 1950s onward. Some of the authors gathered in The Unexpected Louis St‑Laurent touch on these episodes, and perhaps there should have been a chapter on St‑Laurent’s mental state.

Nonetheless, there are some fine pieces among the twenty-two essays. Jean Thérèse Riley, one of his granddaughters, sets the man into his family context with much charm. Stephen Azzi writes well on how St‑Laurent ran his cabinet, and Paul Litt analyzes the way “Uncle Louis” was marketed to the voters so successfully. The volume’s editor, Patrice Dutil, contributes the introduction and three chapters: one on St‑Laurent in government, one on his electoral coalition (with some useful tables), and one (co-authored with Peter M. Ryan) comparing party platforms in St‑Laurent’s three elections. There are also good chapters on immigration, on the slow move toward hospital insurance, and on the death penalty. While the authors do not hide the missteps or the government’s cautious approach to some issues, the overall impression is of a prime minister who modernized Canada and governed well for almost a decade.

The one exception is a politely scathing chapter by Xavier Gélinas, an able historian at the Canadian Museum of History, in Gatineau, who details how St‑Laurent dealt with the French fact. In Gélinas’s view, St‑Laurent did almost nothing to promote the rights and views of Quebec and francophones. He had supported conscription during the war, despite the opposition of francophones, and, although Gélinas does not say this, his government had everything in place to impose conscription if the Cold War had turned hot in the early ’50s. St‑Laurent refused to open diplomatic relations with the Vatican, something Roman Catholics wanted, and, more important, he did little to advance francophones to the senior bureaucratic ranks. He also declined to introduce simultaneous translation into Parliament and to address the need for bilingual government cheques. St‑Laurent, Gélinas maintains, “genuinely believed that French-Canadian nationalism was inherently navel-gazing and mistrustful, that it verged on xenophobia and religious intolerance.” What’s worse, he once said that “the province of Quebec can be a province like any other.” To Gélinas, in effect, St‑Laurent was apparently a vendu, a sellout, which is a harsh judgment indeed.

Gélinas’s interpretation would be a stronger one if he had tried to explain how St‑Laurent won between 57 and 61 percent of the popular vote in Quebec during his three elections as leader. After the 1949 victory, for example, one newspaper wrote that the results constituted “la défaite des ennemis de l’unité nationale et de la race canadienne-française.” Gélinas should perhaps have considered that many in the province might have been getting tired of Duplessis’s variant of conservative Catholic nationalism and preferred St‑Laurent’s brand of an expansive Canadian nationalism instead.

There is one more notable omission among the chapters: defence. The St‑Laurent government, from the late 1940s to its defeat in 1957, was without question Canada’s best peacetime government for the armed forces. On St‑Laurent’s watch, Ottawa signed the North Atlantic Treaty, built the Distant Early Warning Line with the United States, and negotiated the North American Air Defence Agreement. The number of soldiers, sailors, and airmen tripled over that period to some 120,000, and the defence budget rose dramatically from $269 million in 1947–48 to $1.96 billion in 1952 (the percentage of gross domestic product spent on defence by that point was almost 10 percent, the highest outside the world wars). The navy sent destroyers to Korean waters, became leading practitioners of anti-submarine warfare, and fielded an aircraft carrier and state-of-the-art destroyer escorts; the RCAF put fighter jets into continental air defence, sent an air division of twelve squadrons of Sabre fighters overseas to support NATO, and created substantial air transport capabilities. The Canadian Army, meanwhile, had 40,000 soldiers (double the present number), with a brigade group in Korea, from 1951 to the 1953 armistice, and another with NATO that, once it had shaken down, was widely recognized as a top-of-the-line formation. At the same time, defence manufacturing picked up sharply, as did exports. How this subject could have received only a few pages in this book is a mystery.

Nonetheless, The Unexpected Louis St‑Laurent is a fine volume, one of the few recent edited collections held together by more than the binding. If it gives Canadians a new regard for a leader they have forgotten, it will have served its purpose. Judged against our present cadre of leaders, Louis St‑Laurent looks more and more like a giant.

J. L. Granatstein writes on Canadian political and military history. His many books include Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace.

Related Letters and Responses

Robert A. Stairs Peterborough, Ontario