More than a year before the 2015 election, which delivered a Liberal majority government, I had dinner in Ottawa with Gerald Butts, a confidant of Justin Trudeau. I did not know Butts well, our previous contact having been several lunches in Toronto when he had worked for Ontario premier Dalton McGuinty. Until he left the Prime Minister’s Office, in February 2019, I didn’t speak to or hear from Butts after that evening — except once.

I cannot remember all the details of our conversation. I assume it rambled through the usual subjects between political adviser and journalist: policy, personalities, strategies. The Liberals were then in third place in the polls. I do recall, however, that we chewed over and agreed on the premise that Parliament and the country would be well served by having more Indigenous candidates running and winning seats, both to bring their perspective more evidently into national debates and to demonstrate that the political system was not closed to them.

Some months later, Butts sent me an email, reminding me of the part of our conversation about building up Indigenous representation in Ottawa. Look who we are announcing as our candidate in Vancouver Granville, he wrote. It was Jody Wilson-Raybould, exactly the kind of person the two of us had had in mind at our dinner.

Butts attached Wilson-Raybould’s CV, obviously excited about whom the Liberals had attracted to their team. Having perused it, I replied churlishly and impetuously that I was less than impressed. This new star candidate, I pointed out, had worked for two sometimes dysfunctional organizations, the British Columbia Treaty Commission and the British Columbia Assembly of First Nations. I used the word “dysfunctional,” in part, because of divisions — some of them going back centuries — among First Nations that tended to be papered over publicly by rather ritualistic denunciations of governments. These lashings have become the lowest common denominator of acceptable discourse, the kind of rhetoric also served up by premiers at interprovincial meetings vis‑à‑vis the federal government. Both of the organizations that Wilson-Raybould had served were tied to chiefs, and chiefs, as the word suggests and as practice reveals, are not easily herded into agreements.

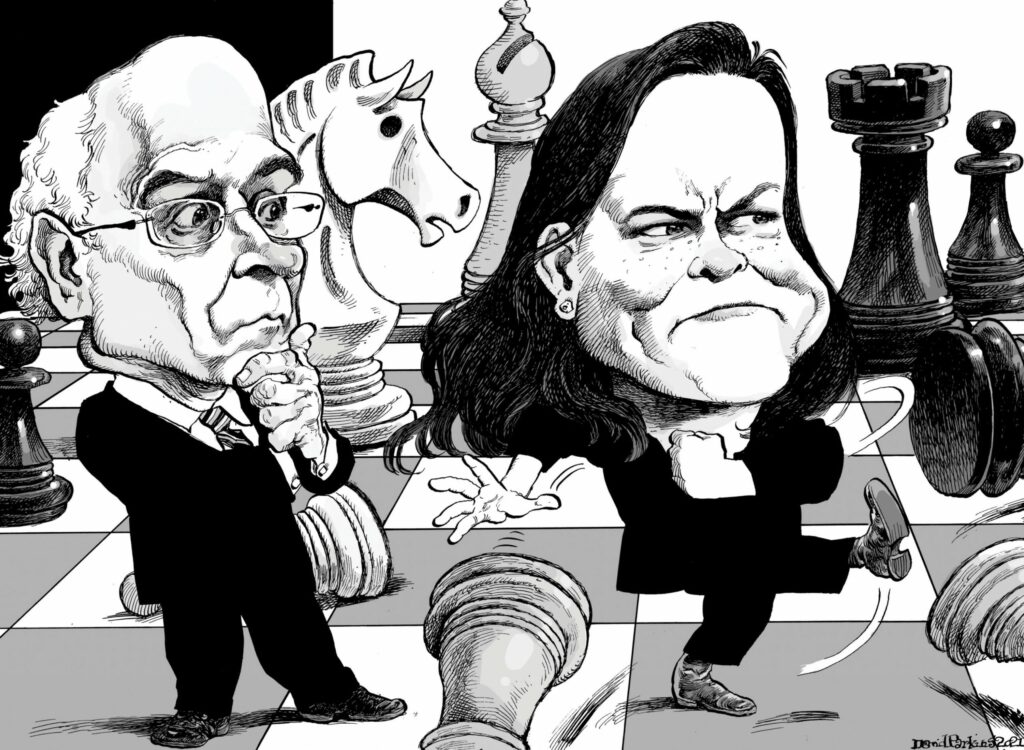

Two different approaches to the game.

David Parkins

I regretted my churlish tone later once I understood that Wilson-Raybould possessed a high intelligence and a serious commitment to the concerns of Indigenous Canadians. She did seem to be an excellent catch for a political party that was giving Indigenous issues more prominence in its platform than any federal party in previous elections.

Justin Trudeau had personally wooed Wilson-Raybould. The Liberal Party election machine, including Butts, pushed aside other contenders for the Vancouver Granville nomination and helped her organize and raise money. On election night, it could rightly savour her victory. As a candidate, she worked hard and galvanized supporters. And while Wilson-Raybould might have convinced herself that she was going to do politics differently, she got nominated and elected the very old-fashioned way, by partisan tactics and the laying on of hands from on high.

Of course, before Trudeau’s first term expired, Butts had resigned from the PMO during a public storm of controversy featuring the prime minister, his advisers, and Wilson-Raybould. She had quit the cabinet (before she could be fired) and been expelled from the Liberal caucus. A national political career that had begun so hopefully ended; her national reputation began to develop in many quarters, but certainly not all, as a martyr to a cause. “Indian” in the Cabinet: Speaking Truth to Power is her version of how hope turned to disillusionment, how policy commitments crumbled under the weight of omnipresent political calculations, how truth became twisted for party gain or to avoid blame, and how those who challenge the holders of real power — the prime minister and his inner circle — are destined for the margins. It is also about how, promises for change notwithstanding, a “colonial” mentality inside the public service and the Liberal Party still guides federal policy toward Indigenous peoples. At least this is how she interprets her time as a cabinet minister.

Wilson-Raybould modestly asserts she does not write too well, but such modesty is misplaced. Her memoir, substance aside, is an excellent read that moves deftly and swiftly — except for several gratuitous profanities and her repeated and therefore tiresome shots at Justin Trudeau, whom she once respected but later came to despise. (At their last meeting, she told him, “I wish that I had never met you.”) That revenge is best served cold does not apply here; indeed, so determined was Wilson-Raybould to wound the prime minister and his party in the 2021 election that she apparently advanced the memoir’s publication date to maximize the hurt it might do to her former colleagues. That kind of animus explains, in part, why the Liberal caucus almost to a person stood and cheered when apprised of her dismissal from their midst. She had made a few close friends in Ottawa but many more enemies.

Wilson-Raybould, with degrees from the University of Victoria and the University of British Columbia, was a rookie MP with fewer than four years practising law as a prosecutor. She was intelligent and determined, and, being of Kwakwaka’wakw descent, she helped the Liberals to highlight their commitment to Indigenous issues. Still, her selection as minister of justice upset all precedents. Normally, rookie ministers are given lesser portfolios to learn the ropes of government. But Wilson-Raybould was ambitious, and the government seemed to have big ambitions for her. So to Justice she went.

Since Confederation, Canada’s justice minister has usually been a politician of long standing or a lawyer with extensive experience in private practice or teaching law. Following Pierre Trudeau, who held the post before becoming prime minister in 1968, the office has been occupied by law deans (Otto Lang, Mark MacGuigan, Anne McLellan), experienced practitioners (Allan Rock, John Turner), and veteran politicians (Ron Basford, Marc Lalonde, Jean Chrétien, Don Johnston, Ray Hnatyshyn, Vic Toews, Rob Nicholson, Peter MacKay). An exception might be Kim Campbell, who entered politics (provincially) after practising for only two years and was made justice minister a year after being elected to the House of Commons.

Always a key portfolio, the ministry gained elevated importance after the enactment of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as many new policy issues were thrust before the courts. Inside government, Justice became a central agency, like the Treasury Board or Finance, asked to vet and comment upon all sorts of decisions before they were announced. Any successful justice minister needs endless energy, personal discipline, knowledge of the law, an agenda of reform, a commitment to fairness — but also experience in politics, which means getting things done in a system that requires an ability to work with colleagues, choose priorities, and make necessary compromises. The shortest distance from A to B in Ottawa is seldom a straight line. Effective ministers must be bifocal, with one focus being policy, the other politics. It was Wilson-Raybould’s failure — or perhaps refusal is a more accurate description — to be bifocal that intensified her anger and chagrin before the SNC-Lavalin affair brought her to an impasse with the prime minister and to the end of her career as a Liberal.

The SNC-Lavalin imbroglio, which Wilson-Raybould explains in considerable detail, consumed plenty of political air for many weeks. The essence of the situation was straightforward, the differences between her and the prime minister clear, the ramifications considerable. The director of public prosecutions wished to charge SNC-Lavalin, the huge engineering and construction firm based in Montreal, with bribery and fraud. The charges related to work it had done years before in Libya, where the passing of money through illicit channels and various forms of baksheesh were the norm for doing business, albeit illegal under Canadian law. Wilson-Raybould was the justice minister, a policy and political position, but she was also attorney general, responsible for the impartial application of Canadian law. She wore two hats, as had all her predecessors here and in the United Kingdom. But she decided she had no discretion to countermand the intention of the director to prosecute the company. “I was simply doing my job of ensuring the law was followed, and trying to ensure the government did not engage in wrongdoing,” she writes.

In her view, the “pressure” she endured from the prime minister, his staff (especially Butts), and other senior officials not to prosecute SNC-Lavalin but rather to negotiate a guilty plea, a fine, and a commitment to corporate reform (a so‑called deferred prosecution) amounted to intolerable interference. Her view was shared by a formidable colleague, Jane Philpott, an excellent health minister who had become a close friend and cabinet comrade-in-arms — a friend who subsequently resigned from cabinet with Wilson-Raybould. The view of unacceptable pressure was later supported by an ethics commissioner’s report, and it was backed by most of the media, especially the Globe and Mail ’s reporters, columnists, editorialists, and op-ed contributors. (The paper had broken and sustained the story courtesy of leaks quite likely, but not certainly, from those close to Wilson-Raybould.)

SNC-Lavalin deployed lobbyists who, through whispers and leaks of their own, claimed the company might fold or up stakes from Canada if dragged into court and found guilty. They argued that executives who were around at the time of the Libyan contracts were no longer employed. The Quebec government and the province’s Liberal MPs, including the prime minister, saw a headstrong federal attorney general whose obstinacy would threaten jobs and weaken a very important company, outcomes that could both be avoided by pursuing a deferred prosecution. Otherwise, things could drag on for years. Moreover, as any prosecutor knows, counting on a particular court judgment can be a mug’s game, especially in instances like this — with testimony from witnesses about events some years back in a shady, corrupt country. But the director of public prosecutions was determined to proceed, and Wilson-Raybould backed her to the hilt.

Enter the Shawcross Doctrine, named after a mid-twentieth-century British attorney general. The doctrine has several parts. The AG should take account of matters of public interest. Cabinet ministers can offer “advice” to the AG, but they are not to apply “pressure.” Decisions about how to proceed lie wholly within the AG’s prerogative. Justin Trudeau, his staff, and various senior officials insisted their arguments and remonstrances with Wilson-Raybould amounted to “advice”; she took them as “pressure.” She would not yield to what she considered law-breaking. She would tell “truth to power,” one of her favourite phrases of self-description in the book. She was principled; they were not.

After Wilson-Raybould was gone, SNC-Lavalin pleaded guilty to one count of fraud and paid a $280-million fine. Having been expelled from the party, Wilson-Raybould ran as an Independent in the 2019 election and retained her Vancouver Granville seat; her friend Jane Philpott also ran as an Independent, in Markham–Stouffville, but lost. Wilson-Raybould did not contest the 2021 election and instead set about writing this sulphureous memoir.

“I went to Ottawa hoping to be an Indigenous woman in the Cabinet and contribute teachings and learnings from the Indigenous experience in this country to making good decisions and setting better policy,” she writes. “I ended up being treated as the ‘Indian’ in the Cabinet.” By employing the word, with its increasingly pejorative sense, to describe herself, Wilson-Raybould implies that her colleagues looked down on her. Repeatedly, she describes her difficulties in Ottawa as flowing from “racism” and “misogyny.” Maybe that’s the case, although the evidence she adduces to support this claim is thin, especially in a cabinet with equal representation for women and men.

The government in which Wilson-Raybould served significantly boosted spending for Indigenous programs and treaty settlements. It allowed her to change litigation instructions to make contesting Indigenous positions less likely. It also created a commissioner of Indigenous languages and adopted into law — the only country to do so — the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Among other recent developments, there have also been the symbolic decisions, both during and after her time in cabinet: stripping names of Fathers of Confederation from buildings; creating a national holiday around truth and reconciliation; adopting the trope of systemic racism; flying the Canadian flag at half-mast for months, following the discovery of unmarked graves at the sites of former residential schools; and so on. Personalities aside, what shattered her relationship with the government more than anything else came over such matters. What the government believed to be earnest and sincere steps forward she considered depressingly inadequate.

Wilson-Raybould carried into federal politics not only a career in Indigenous politics in British Columbia — with dynamics quite different than what she found in Ottawa — but a background as the child of a distinguished family, even nobility (her Kwak’wala name, Puglaas, means “woman born to noble people”). Her grandmother, whom she adored, was named Pugladee, the highest-ranking name in their clan, from northern Vancouver Island. Her father, Bill, was its hereditary chief. (Her mother is of English and German descent.) Wilson-Raybould did not grow up on a reserve, although she owns a house on one, at Cape Mudge, and she attended the public school system in Comox. Her parents divorced soon after she was born, and though her father was seldom at home, he remained an important force in her life. “My identity and reality were, and are, as an Indigenous person,” she writes.

Before running for federal office, Wilson-Raybould had developed and articulated in writing and speeches a conception of how First Nations (she says nothing about Métis and Inuit communities in her book) must recapture full self-determination within Canada. Self-determination, if it is to mean anything, would involve self-government within a defined territory, with powers over education, health, policing, social services, economic development, and more — roughly akin to the powers of the provinces, with a large degree of own-source revenue raised by taxation, shares of royalties, fees, and so forth. The Indian Act would be scrapped. Confederation, she asserts, would be shaped as it ought to have been from the beginning, as a “nation-to-nation” relationship.

This aspiration, of course, crashes into demographic reality. Across Canada, there are 634 First Nations communities, fifty nations, and an equal number of language groups. According to Statistics Canada, more than 50 percent of First Nations have fewer than 1,000 people. Overall, 40 percent of those with Indian status live on reserves, while 45 percent live in urban areas. More than two-thirds of all reserves have fewer than 500 people. To further complicate matters, in Wilson-Raybould’s home province, where there are few original treaties, many communities make overlapping claims to territory. At no point does she acknowledge these facts on the ground, which would limit, at least to some extent, the capacities of any group — Indigenous or otherwise — to achieve full self-determination. But anything less than full support for her vision from her cabinet colleagues she imputed to insincerity, failure to understand, or a lack of interest.

A sad but telling example of the breakdown over policy was the deterioration of Wilson-Raybould’s relationship with Carolyn Bennett, the Crown-Indigenous affairs minister from 2015 to 2021. Initially, the two had an excellent rapport, but over time it deteriorated as Wilson-Raybould came to believe Bennett did not really accept a total reset of relations with First Nations. Mid-mandate, Wilson-Raybould writes, “Carolyn and I would find ourselves increasingly at an impasse and would even have a few blow‑ups about issues like this. I felt there was a paternalism emerging in the exchanges, and it made me push back even harder.” A bit of nastiness ensued when Wilson-Raybould, by this point an Independent MP, questioned the need for an election in 2021. “Pension?” Bennett wrote in a private message to her estranged ally, implying she wanted a later election to ensure she would have served long enough to secure a pension. Wilson-Raybould immediately made public the exchange, calling it “racist” and “misogynist.” Bennett then apologized. The point here is simple: if Wilson-Raybould couldn’t get along with a ministerial colleague with whom she had once been friends and who was overtly sympathetic to Indigenous causes, it’s little wonder her influence in cabinet withered and personal relationships were strained.

Of her other cabinet colleagues, except Jane Philpott, she says little or nothing. It’s almost as if they did not exist and Wilson-Raybould’s world consisted largely of herself, her staff, and the Prime Minister’s Office locked in testy combat from early in the mandate until the final break. And even after that, her vituperation continued. She offers sweeping denunciations of a “warped, dysfunctional political culture” to which cabinet colleagues acquiesced to keep their jobs and curry favour with the prime minister and his entourage. And at no point does she give any of them, except Philpott, any credit for having convictions other than to remain in office. Or at least she doesn’t mention, let alone laud, ministers who do not fit that description.

Wilson-Raybould spent much more time working in Indigenous institutions than in federal politics. In the former, she honed her skills as an advocate. “I do not want to romanticize Indigenous politics,” she writes, only to do just that, contrasting in a caricature what she describes as deliberative, consultative, respectful ways of doing things with parliamentary government, the “worst reality show,” where people “do and say whatever is necessary to hold onto power, with decisions being driven by political expediency and not an authentic confrontation with the challenges we face as a country, as a world, and as humans.” This sort of overweening moral superiority, reflected throughout the memoir, is a more important explanation of her Parliament Hill isolation than being an “Indian” in the cabinet.

Of course, Wilson-Raybould is hardly the first writer to bemoan the increasingly centralized control of the PMO. She, like others, is right to do so, and she offers telling evidence of that control. Complaints of this kind have been made at least since Pierre Trudeau was prime minister, but they have become louder and with reason. The growth in the size of government has heightened the need for coordination. Social media — churning out content twenty-four hours a day — has put officials on edge, since bad news and surprises can arrive from anywhere, at any time. Cabinets have fewer heavyweights in them since it is harder to attract people of superior intelligence and experience into public life, and those like Wilson-Raybould can easily become discouraged, although relatively few become as bitter.

Although Wilson-Raybould seemed surprised and let down by the exigencies of partisan politics and the many calculations that infuse themselves into policy, these manoeuvrings have always been part of what we call “democracy” (except perhaps during times of war). There is no democratic state where policy and politics do not intermingle. To suggest otherwise is to display a startling naïveté mixed with a powerful sense of personal virtue. The battle for power is, yes, about ego and ambition. But power — constrained by courts, conventions, elections, the media, and that beast called public opinion — is also there to be used by one group of women and men pursuing their ideas for the country, arguing with the opposition but also debating among themselves. And these debates almost always involve compromises to account for what the great liberal intellectual Isaiah Berlin, borrowing from Kant, called the “crooked timber of humanity.” Circles of the eternally virtuous, after all, are found only in heaven.

In early 2019, during the parliamentary hearings into the SNC-Lavalin affair, Wilson-Raybould released a verbatim account of a conversation she had had with Michael Wernick, the clerk of the Privy Council. In it, the country’s senior civil servant repeatedly informed the attorney general that the prime minister was unhappy with the position she had taken, which she construed as the kind of unacceptable, even illegal “pressure” that she should not endure. Wilson-Raybould had taped the conversation without Wernick’s knowledge, an act that flouted honour and defied the norms of ethical conduct. One can only imagine what would have happened if the roles had been reversed: a conversation of hers taped without her consent, then publicly released to embarrass her. But in her crusade against Trudeau, she was prepared to let honour and ethics be damned if it demonstrated how the government had tried dishonourably, as she saw matters, to pressure her in the SNC-Lavalin case.

Whatever Wernick thinks about the release of the taped conversation remains unsaid in his own slim book, Governing Canada: A Guide to the Tradecraft of Politics. Whereas Wilson-Raybould’s memoir is full of anecdotes, reminiscences of her life in and out of politics, broadsides against those who crossed her, accolades for those who assisted her, and recommendations for opening up the government, nary a live person appears in Wernick’s “guide,” except for references to how prime ministers he served throughout his career organized their cabinets, schedules, and priorities. He passes judgment on none, for his book is written in the form of advice to generic prime ministers, ministers, and deputy ministers about how Ottawa actually runs and the pressures that will play on those who occupy its highest positions.

Wernick knows something about these matters from the inside, having been a long-serving deputy minister, including a prolonged stint with Indian Affairs and Northern Development (as it was then called); deputy secretary to the cabinet; and then clerk of the Privy Council. By his reckoning, he was in the cabinet room for meetings about 250 times.

As a kind of primer, Governing Canada is not a Wilson-Raybould morality play, with heroes and villains, but an account of the real world of government. Wernick believes, insider par excellence that he was, that all governments blend policy and politics. Their leaders must be bifocal, or they will fail. He writes a sentence that might make Wilson-Raybould cringe: “Politics is always present in the deliberations of the elected, as it should be in a democracy.” This is a book that accepts the political dimensions of government as indispensable.

There be dragons, Wernick advises would‑be prime ministers: the media, usually of the gotcha type; the opposition parties, always sniffing for advantage; the provincial premiers who individually might be cooperative but collectively find it expedient to caterwaul about Ottawa; interest groups pressing their case. For navigating the inside of government, he offers a series of rules and suggestions, such as “You will not be successful if you hang on to the same closed circle of close advisors and confidants for your whole time in office” and “Use one-on-one meetings sparingly” (instead, require ministers to make their case in front of others). He also encourages the aspiring prime minister to judge ministers and advisers, in part, by how they “anticipate the politics of a situation” and by their skills in developing creative policy solutions.

As for the hypothetical cabinet member, he advises, “You will want to cultivate a reputation as someone who should be listened to because you know your stuff. That means not only showing a command of your portfolio’s subject matter but also having insight into the politics surrounding it and your part of Canada.” And remember, “you can count on the prime minister to defend you — until the prime minister doesn’t.” Wernick offers yet another truism relevant to Wilson-Raybould’s demise: “Never forget that the PMO is fiercely loyal to the current prime minister and that if the staff feel threatened, they will attempt to cut potential threats down to size.” Ministers should always “think of a solar system with the prime minister at the centre.”

Wernick is not judgmental but descriptive. He explains the world as it is, from his civil service perspective, not as it might be. His is a survival guide for a system of governing that, if the polls can be believed, is leaving Canadians ever more disillusioned and shut out. The exercise of power he describes increasingly feels to citizens — as it did to Wilson-Raybould when she was on the inside — as if the balance between policy and politics has tilted too much toward media manipulation, spin, photo ops, headline-grabbing announcements, evasions, and glib talk. For this, the shrunken national media is partly to blame, because it mistakes the urgent for the important and is itself preoccupied by spin over substance. And just try prying out of the government, even on background, solid information beyond what is in the public domain.

Wernick insists there has never been more publicly available information. That is perhaps how matters look to him, but from the outside, the government is like a sound machine on autopilot, spinning the same messages, phrases, and clichés. The Trudeau Liberals, in those pre-2015-election days, promised to do politics differently after the gloomy, tight-lipped Stephen Harper years. The past two minority governments suggest that the Liberals, for many reasons — and only a small one being Wilson-Raybould’s saga — have lost their lustre.

Jeffrey Simpson was the Globe and Mail’s national affairs columnist for thirty-two years.