It is an unfortunate fashion among book editors these days to encourage their non-fiction authors to showcase the most dramatic material first. The intent is to hook the reader into reading more, as if having paid for the book weren’t incentive enough. But the result is more like throwing us into the deep end to flap around in ignorance and irritation about what the hell is going on. Who are these people, how did they get here, what’s their significance? By the time we reach the answers in chronological order, we must go back to reread the opening to make sense of it.

Thus, Where to from Here begins at the end. The scene: Ottawa, August 17, 2020. The actors: Bill Morneau, Canada’s minister of finance, and Justin Trudeau, the prime minister, alone at last, mano-a-mano. The plot: Morneau has come to tender his resignation. And we, the readers, are invited to be in the room where it happened. Except nothing happens. Or, rather, what happens is so underwhelming, so coded, so repressed that neither Morneau nor Trudeau seems to have any better understanding than we do about what the hell is going on.

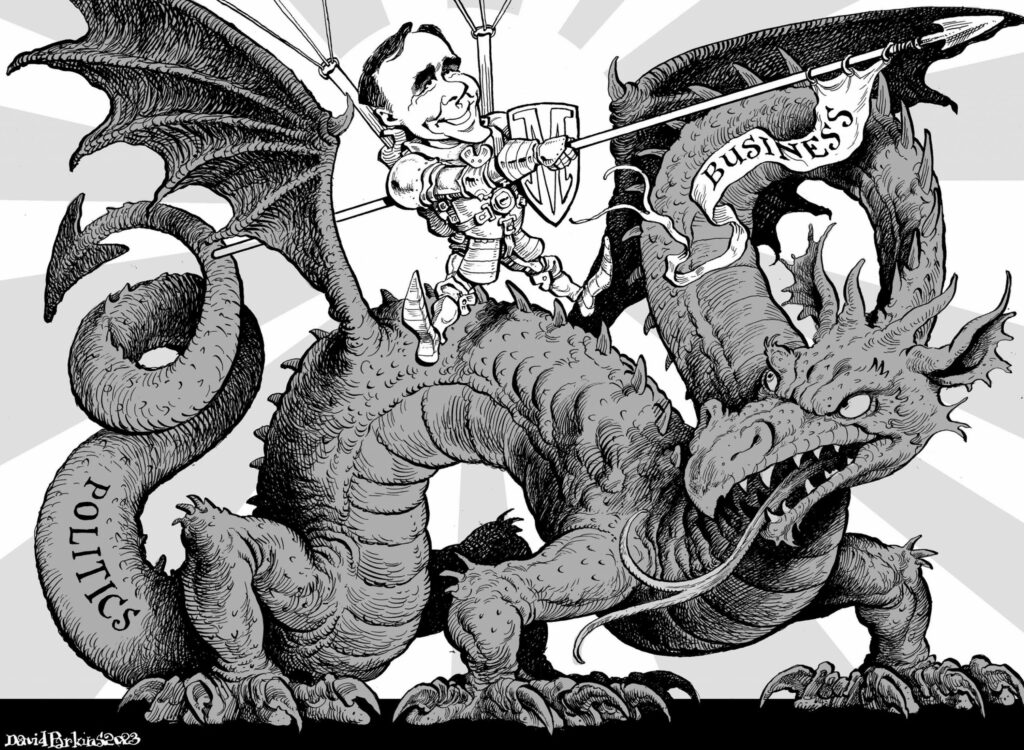

The Bay Street executive dared to parachute into the dragon’s den that is Ottawa.

David Parkins

What brought these two intelligent, reasonable, accomplished adults to this climactic meeting? A clash of principles? A conflict over policies? A scandal? A burnout? A putsch?

Morneau complains about some malicious leaks in the press.

Trudeau says that he’s not aware of them.

Morneau thinks he’s either willfully ignorant or deliberately lying.

Trudeau accepts his resignation.

Morneau asks for help getting a job in Paris.

Trudeau agrees.

The two men shake hands.

Curtain.

So off we go — a tad worried that this anti-climax doesn’t bode well for Morneau’s ability as a storyteller — to learn more. After all, only a few wealthy businessmen from Toronto have dared to enter the dragon’s den of federal politics and fewer have emerged unmauled.

Morneau insists — too much — that he wasn’t naive. Perhaps, but he does seem to have been seriously deluded. He assumed, by his own telling, that he could transfer his success as the CEO of a family enterprise into the governing of Canada without a day’s experience as a backbencher or cabinet minister.

Morneau approves of star candidates such as himself —“individuals who demonstrate the required talent and dedication in specific areas of responsibility”— being parachuted into ridings by the Liberal hierarchy, sort of like first-class passengers being ushered into the Maple Leaf Lounge. He seems to take it as his due when Gerry Butts, Trudeau’s closest adviser, invites him to run for Parliament in a safe Liberal seat in 2015. “I wanted, and indeed expected, the Party leader’s expressing of support for my nomination victory,” he foreshadows, “but it never arrived.”

Nor does Morneau seem surprised to become the first rookie MP in Canadian history to be appointed finance minister, as though anything less would have been an insult. He brought in his own furniture and artwork to spruce up the government-issue space he was assigned, unsuitable apparently to his rank and taste, and then settled with remarkable ease into his first year — a tribute to both his smarts and the universal language of numbers.

Morneau sounds happiest sitting in his office with his capable, hard-working staff poring over the ledgers, weighing the inputs and outputs. The PM and the PMO, too busy learning their own ropes, left him “unimpeded and largely free of second-guessing.” They overrode his preferred chief of staff in favour of their own guy, it’s true, but their guy turned out to be a very good choice. Morneau raised the Working Income Tax Benefit level without prior approval, but that’s what was required to get a deal done, and, besides, he had the trust of the prime minister. “This permitted me to apply my judgment in the best interests of the country, and he agreed with the decision I made after the fact.”

Morneau’s confidence, his conceit, isn’t necessarily a character flaw. No one is well served by an insecure, mousy leader, and he comes across as an affable, industrious patrician with liberal values and a sincere desire to do good. The problem comes when success, particularly financial success, makes a drug of power, and you become addicted to getting your own way. You need power. You’re entitled to power. And you become irritated, even angry, whenever your power is trumped by someone else’s.

Once sworn in, Morneau did something that Trudeau and his political team seldom did: he sought advice from a few old pros, including Jean Chrétien, Paul Martin, and Michael Wilson, about how best to do his new job and what pitfalls to avoid. Their advice boiled down to a simple warning: The relationship between a prime minister and a finance minister comes with built-in tensions. The jobs are different, so the goals may conflict. “The more independent you are, the more effective you will be,” Chrétien told him, “but the more independent you are, the more you will be at risk.”

Morneau listened, but he didn’t want to hear about tensions and conflicts. Instead, he remembered what he learned at his father’s knee: “Never underestimate the value of strong relationships in your business and personal lives.”

Hadn’t that lesson enabled Bill to take his inheritance and grow it into an international pension and benefits company? Hadn’t it served him well as the chair of St. Michael’s Hospital, Covenant House, and the C. D. Howe Institute? So why wouldn’t it work just as well in politics and government? But it takes two to tango, and Justin Trudeau proved surprisingly unwilling to dance. The smiling extrovert who can charm a crowd and work a room better than almost every other retail politician in the Western world turned out to be a complicated introvert who shies away from personal interactions with all but a trusted few, especially if there’s the slightest chance of a direct confrontation — a contradiction that gives wings to the widespread public impression that he’s a phony.

Morneau never became one of the trusted few. No ski holidays together in British Columbia; no family barbecues at Harrington Lake; no fireside chats late into the night grappling with the intricacies of pension reform; no war room where he and the PM huddled over the charts — maybe with one or two key advisers, like in business, but better alone — to hammer out a path to economic growth. “The final decision rests with the prime minister, as it must,” Morneau begrudges. “But it’s easy to see that the only way to encourage the necessary give-and-take and accept the practical solution is via a close relationship between the two individuals occupying these positions, and this simply did not exist between Prime Minister Trudeau and me.”

Morneau takes pride in his ability to build close relationships. His was old-style elite accommodation in an age of anti-elitism. His staff at Finance, certain members of the opposition, many of his counterparts at the G20 and in the provinces, Saudi Arabia’s finance minister (before that journalist was chopped to pieces, the author footnotes), a key economic adviser to Xi Jinping (before the seizure of the two Michaels, that is) — Morneau got buddy-buddy with them all. He even established a quick rapport with Steven Mnuchin, Donald Trump’s treasury secretary, “built on shared respect and our business backgrounds,” and was given a choice seat at Mnuchin’s wedding feast with Ivanka Trump, Jared Kushner, and Michael Milken, schmoozing for the sake of saving NAFTA. So he was genuinely perplexed, galled, even hurt, when he couldn’t get close to the only guy who mattered.

Governing Canada, it seems, was all about himself and the prime minister. He was offended when Trudeau declared that all ministries are equal, he says, because it led to bad management practices (though one intuits that he was miffed because the statement didn’t recognize his specialness). He resisted being ordered to team up with another minister on the Canada Child Benefit, expecting “a laborious process with no real advantage to be gained by including my colleague,” though Jean-Yves Duclos turned out to be an effective player. François-Philippe Champagne, Jane Philpott, and Catherine McKenna get passing marks, though usually in the context of contributing to the success of Bill Morneau. Nothing about what Navdeep Bains was achieving over at Industry or Scott Brison at Treasury Board or Jim Carr at Natural Resources. Chrystia Freeland gets a tip of the hat for leading the NAFTA renegotiations, but Morneau devotes more space to criticizing a speech she gave in Washington that pissed off his pal Mnuchin.

For the most part, Morneau portrays his cabinet colleagues as faceless ministers —“chosen not necessarily for what they brought to the business of governing but to the needs of promotion”— who constantly demanded money for their pet programs. He almost never grants that they might have been trying to get the funds necessary to do a good job, just as he would do, or that their programs might not have been designed solely for political expediency. And by defining the most qualified minister as the most experienced manager, he could only hope that the others were running their departments as well as he was running his.

But his true ire is directed at the Prime Minister’s Office. In his judgment, the talented team that won the 2015 election didn’t have the talent to manage the government, which meant, among the regular screw-ups, a focus on image and communications over policy and ideas, a failure to execute long-term goals, and the lack of a “healthy tension between policies that focused on growth versus policies that focused on fairer distribution of wealth.”

Justin Trudeau didn’t just tolerate those flaws, he personified them. “Unfortunately,” Morneau writes, “during the first year or so after securing his majority he apparently failed to ask himself if the team that had contributed to his success was also the best to help govern the country.”

It comes as a surprise to the reader, therefore, when Morneau admits to shifting about 80 percent of his time to activities “with no direct linkage to the task of discussing, formulating and executing policies that dealt with serious national concerns,” though his efforts yielded little improvement to his own image and communications. When he went after the loopholes used by personal corporations to enable high-earning owners to lower their tax bills, with the prime minister’s personal backing, he felt thrown to the wolves by the PMO. “I was not only assigned to shape and direct the program, but to lead the communications effort and deal with challenges to our plan. I was on my own.” Funny, that’s where we thought he wanted to be.

Power fucks with your head. It makes you demand the best table in every restaurant and an escort to the front of every queue. It insulates you from ordinary people and their needs. You can’t resist feeling better than those you consider beneath you, which typically means those with less money, or just about everyone.

Which goes a long way, I believe, to explaining why CEOs and billionaires don’t just dislike politicians and bureaucrats, they despise them. Trump and the plutocrats who enabled him always sounded angrier than the displaced workers they conned into voting for him. As a banker said to my wife, at a dinner party during the 2018 Ontario election, “Kathleen Wynne is a piece of shit.”

Governments possess the only power greater than that of corporations, so corporations have spent decades figuring out ways to cap, harness, reduce, and eradicate that power. They invest heavily in the careers of politicians, lawyers, academics, and journalists who would go into battle against the nanny state, its size, its regulations, its spending, its taxes. They mobilize free trade, computer technologies, and offshore accounts to escape the grip of national jurisdictions. When that gets them only so far, corporations use the threat of relocating their jobs, their capital, and their genius to some other jurisdiction to extort the deregulation, tax cuts, and boondoggles that go straight to their bottom lines.

One of the rare times the word “regret” appears in Morneau’s book pertains to his support for the Liberals’ increase in taxes on the upper 1 percent of income earners. In hindsight, he writes, it frustrated the business community, reduced business confidence in the government, and “made it difficult to have a constructive dialogue with the people prepared to invest in research and development to benefit the country.” Worst of all, it brought in less money than he expected. And why was that? Because, as his own department warned, “when you tell people you are going to raise their taxes, they react in a way that reduces their exposure to your new measure.” Welcome, sir, to Panama.

Canada has been spared the worst of the wrath, at least in public. Our culture is imbued with civility and deference. Our history has necessitated a mixed economy. Our constitution has split sovereignty between the central and provincial governments. Our laws have put obstacles in the way of buying politicians and elections. Our regulations have tolerated, even encouraged quasi-monopolies of banks, telecoms, and family-owned empires. Our tax rates and investment incentives need to be competitive with those of the United States. Yet the anger has seeped in, not only through the right-wing populism of the American media but through the neo-liberal hegemony of post-industrial capitalism. And not only into the encampments of the Freedom Convoy but into the boardrooms of Bay Street, from where Bill Morneau rode out on his high horse to teach Ottawa how to get things done.

Bill Morneau seldom sounds angry, just disappointed and frustrated. Nor does he sound like an ideologue. On the contrary, he worships at the altar of pragmatism. A long-time Liberal, he opposed Stephen Harper’s draconian austerity and understands that government is “the ultimate instrument to address major social challenges.” He supports a carbon tax, an infrastructure bank, defence procurement, affordable housing, some version of pharmacare, and the expenditure of tens of millions of dollars to renovate 24 Sussex into a residence worthy of the leader of a G7 nation. Former Ontario premier Kathleen Wynne is even “something of a hero” to him.

But try as he did to fit the square peg of business into the round hole of government, Morneau kept encountering fundamental differences. He would have spared himself a lot of grief if he had picked up a copy of Systems of Survival, Jane Jacobs’s insightful meditation on the two distinct moral syndromes that characterize commerce and politics, each necessary and obvious in its own domain. Commerce is basically about profit, efficiency, invention, thrift, and the creation of wealth. Politics is basically about votes, accountability, stability, largesse, and the redistribution of wealth. And trouble always arises, Jacobs warns, when they collide.

Louis St-Laurent presided as chairman of the board over one of the best-managed governments in Canadian history, and he was turfed out of office by a populist clown. Pierre Trudeau was too obsessed with preserving the federation and entrenching a charter of rights to concern himself with 18 percent interest rates, and he won four elections. If Bill Morneau wanted an education in true disappointment and frustration, he should have sat for five years on an opposition bench.

Even in business terms, Morneau fails to realize that government isn’t all about management, as important as management is. He makes a clear distinction, for example, between his father as an entrepreneur and himself as a manager — without seeing that a cabinet minister is more like an owner than like an operator. Elected by the people, politicians set the goals, the strategies, and the policies, then leave the implementation to their civil servants under the leadership of the Clerk of the Privy Council. The ministers remain ultimately responsible, of course, but the skills they need are not managerial skills, per se, any more than a bureaucrat needs to have the skills of a politician.

From Morneau’s description, the basic trouble with Trudeau’s PMO wasn’t really its incompetence in managing the operations of government but its incompetence in managing the politics of government — two quite separate problems. Staffers kept shooting themselves in the foot with avoidable public relations disasters, stomping unnecessarily into ministerial territory, rushing through unrefined legislation and ill-considered appointments, and not paying adequate attention to the massaging of egos such as Bill Morneau’s.

Indeed, Ottawa remains full of disgruntled ministers and Liberal MPs complaining about their lack of direct access to the prime minister, the interference of the PMO, and the disregard with which they’re treated. A lot of that bitching is as old as the hills: a prime minister’s time is the rarest commodity in Ottawa. It’s safer to go after the king’s advisers than after the king, and ministers have to work to maintain a sense of humility when everybody around them is begging, bowing, and beseeching. Their discontent is compounded by the PM’s own special sense of entitlement. Trudeau the Younger inherited a misapprehension from his father: that because he snatched his party from the jaws of defeat, the ministers and MPs owe their jobs to him, whereas, in theory and practice, because enough of them went out and got themselves elected, he owes his job to them.

Staff incompetence led to a lot of dumb behaviour with dysfunctional consequences, but it was hardly at the root of Morneau’s issues; if it were, everything could have been solved by replacing the PMO with a team of McKinsey consultants. Not only does government have a system of survival, it also has significant handicaps that Morneau fails to address sufficiently: The need to face a daily barrage of criticism in public from the opposition and the media. The need for slow, meticulous analysis over hasty, instinctual action. The need to respond to a myriad of competing interests, players, and goals. The need to account for every dollar spent. The need to assume expenditures that no private enterprise could ever justify.

Take, for example, Morneau’s opposition to the Liberal promise not to raise the eligibility age for retirement benefits from sixty-five to sixty-seven — a promise made to garner votes in a tight election, Morneau concedes, but expensive and “economically illiterate.” But he slides too easily past the original sin: “Globalization saw some firms move their operations offshore. In many cases, companies severely reduced or ceased operations in response to technological advances, straining their ability to fund their defined benefit pensions. Increasingly, the pace of change convinced many employers that the long-term financial commitment demanded by a defined benefit pension plan no longer made business sense.” In short, they shifted the responsibility first to their employees and then to the state.

Although Morneau is generous in his praise of Canada’s civil service, it deserves even more praise for coming through four decades of abuse, decimation, cutbacks, and polarization with any management skills left at all. One of the first things he did to kick-start his productivity agenda was to look elsewhere and establish the Advisory Council on Economic Growth, consisting of fourteen Canadian and international business and academic leaders under the chairmanship of Dominic Barton, then McKinsey’s CEO. It was a unique approach, Morneau writes, “in that we had the outside experts work closely with our team at finance in developing new policy objectives.”

The council’s three primary recommendations — strategic investment in infrastructure, more foreign investment, exceptional talent through immigration — were, of course, harder to execute than to articulate, but Morneau offers no evidence that they met with strong opposition in the cabinet and the PMO, which subsequently faced a storm of controversy about government by McKinsey. And though he rarely got any private meetings with Justin Trudeau, Morneau always had Gerry Butts at the other end of the line, ready to receive the benefits of his wisdom.

In fact, for all Morneau’s lamentations about mismanagement, he boasts that the Liberals were able to fulfill “at least 90 percent” of their 353 election promises in their first term. They introduced the Canada Child Benefit, cut taxes for the middle class, revamped the Canada Pension Plan, legalized marijuana, rejigged NAFTA and secured two other major trade deals, doubled immigration, bought a pipeline, achieved gender parity in the cabinet, and began the long-overdue reconciliation process with Indigenous peoples, with a national daycare program and a health care deal with the provinces soon to follow — all in a world of Trump, Brexit, China, and Russia. Good stuff, according to Morneau, just not what he would have prioritized.

Justin Trudeau’s second election as leader was held on October 21, 2019, and he returned to power with a minority government — a more damning critique of the wizards in the PMO than any revelation in Morneau’s book. I mean, if they wanted to keep messing around with the ministers in the name of electability, they sure as hell should have delivered. (They were to do even worse in 2021, when they foisted an unwanted, unneeded election on the Canadian people, having convinced themselves but few others that it would result in a majority.)

After an unconscionable silence, Morneau was invited to carry on as finance minister, and work on legislation new and old resumed when the Forty-Third Parliament opened in the first week of December. Rumours soon began to circulate about a deadly virus in China. Cases started showing up in North America in January. The following month, hospital admissions and death tolls climbed dramatically around the world. Canadians were urged to isolate at home in March, when schools and businesses were closed, the border with the United States was shut, and workers became unemployed. Millions of people needed immediate cash for food and rent, and the only viable source of relief was the federal government.

There wasn’t the time or the staff for fine-tuning and guardrails. It was an unexpected foreign invasion, albeit by a virus rather than an army, and hundreds of thousands of lives were at risk. Unprecedented amounts of money flew out from the national coffers, the federal debt and deficit soared, and only Bill Morneau (we read) played the good boy trying to hold back the flood by poking his little finger into the large hole in the dike.

Yes, some people kept a few thousand dollars more than they deserved on the basis of their measly earnings. Yes, some large corporations diverted millions into feathering their own nests or profiteering from the pandemic. But by nearly all statistical assessments, the Canadian government did better than most. Even Morneau, looking back, expresses pleasant surprise at how many positive steps were taken, especially when the decisions had to be made on the fly.

That was the beginning of more than a year of exhausting, heroic sixteen-hour days requiring the invention of policies and programs with monikers like CERB, CEBA, CEWS, and CSSG on a scale that no peacetime government anywhere had ever imagined. It was also the beginning of the end of Bill Morneau. His authority got swept up in the maelstrom. Numbers that he had approved got bigger when announced, climbing upward without his say-so. Grants that he had ruled ineffective were distributed anyway. Half-baked schemes cooked up in a backroom were launched, he says, for the sake of sound bites, political points, and populist wedges, including the luxury tax on yachts and private aircraft.

One can sympathize with how disheartened and infuriated a proud, prudent guy like Morneau must have felt. But that’s not how it went, we discover, when he and the prime minister cooked up their own half-baked scheme to put $900 million into the hands of a small charitable organization to invent youth projects for which it had no track record or expertise. The difference? Well, you see, Morneau and Trudeau had a relationship with the two brothers at WE — great guys — and the fallout was all about politics.

In happier days, Morneau could have phoned Gerry Butts over in the PMO to sort it all out. But Butts was no longer over in the PMO, having resigned in February 2019 in the wake of the SNC-Lavalin scandal, in which he and the prime minister were accused of pressuring the minister of justice into interfering with a court case involving the Montreal-based engineering company. It blew into a nasty, he-said-she-said battle when Jody Wilson-Raybould and Jane Philpott resigned from the cabinet as a matter of principle.

This episode might appear to fit perfectly into Morneau’s narrative — isolated PM and intrusive PMO fail to build personal relationship with senior minister — but here he pulls his punches. First, because he happened to agree with Trudeau and Butts on the substance of the issue. Second, because Wilson-Raybould’s “fierce independence” meant that “Jody’s views were often not aligned with those of the broader team.”

“Having kept her in that job as long as he did, despite many signs of problems in their relationship,” Morneau writes, “the PM was left in an impossible position. If he kept her on, he accepted that a key portfolio was being managed in a way that was inconsistent with his direction. But any attempt to move her from that role would invariably be seen as a demotion (at least by her) that she would not tolerate.”

Wise words, but who else arrived in the cabinet as a star candidate with a powerful constituency but with no roots in the party, a fierce independence, and views that often didn’t align with those of the broader team? Morneau never looks in the mirror, except to admire himself. In August 2020, he let his emotions override his generally placid nature and demanded to meet with the prime minister, alone, at last.

Back we go to chapter 1. It makes sense now, sort of. As forewarned, he was caught in the age-old tension between Finance and the other ministries over who gets to spend what and how much. Worse, he felt relegated to a secondary status. “My job of providing counsel and direction where fiscal matters were concerned had deteriorated into serving as something between a figurehead and a rubber stamp,” he laments. “That’s not why I wanted the position of finance minister.”

What’s still missing, despite the long list of betrayals, humiliations, and grievances, is how things reached this pass. Morneau could have fought back to regain control, like Chrétien in 1978 and Wilson in 1985, and stayed. He could have kept going and dared the prime minister to fire him, like Martin in 2002. He never tells of insisting on a confrontation with Trudeau, or thumping a table at the PMO with threats to go public, or building alliances in the cabinet and caucus, or defusing those insidious leaks with leaks of his own. Clearly passive-aggressive, he admits to lacking “the hard edge necessary to fight,” and it seems to have been beneath his dignity to wrestle for a power to which he — chair of Morneau Shepell, London School of Economics (MSc), INSEAD (MBA), multimillionaire, philanthropist — was entitled. So, like Turner in 1975, he quit.

Fair enough. But why not go out with his guns blazing? Why not give vent at last to what he believed was seriously wrong with Trudeau’s leadership and what Canada must do to grow its economy? No, Morneau was too — what’s the right word? respectful, civil, nice, weak, timid, cowardly? — to speak truth to power. And, oh yeah, there’s that job in Paris. So their tête-à-tête all came down to some damn leaks.

True to form, Trudeau didn’t try to probe into Morneau’s psyche, or see what could be done to staunch his wounds, or butter him up with a few bromantic words, or talk him into changing his mind. The prince of empathy showed no empathy. The master of apology offered no apology. Even a boxer’s punch in the nose would have been a personal interaction. No coffee was served. The whole thing was over in half an hour.

Bill Morneau returned to Toronto, relieved and relaxed, with a Rolodex stuffed with new relationships and his privacy restored. No more total strangers interrupting his dinner with suggestions for the next budget. No more atonement for the villa in France. No more aspersions on his good name and unquestionable honesty. Let Chrystia Freeland worry about the deficit — he was dropping the mic.

But first this book, less a farewell letter to his party and prime minister than a backward kick in the groin to those who chose to remain behind to fight the good fight for the future of Canada. Morneau turns out to be no stronger than Jody Wilson-Raybould when it comes to team loyalty and no tougher than Prince Harry when it comes to thin skin. And though we well understand why trashing Justin Trudeau would help promote a book subtitled A Path to Canadian Prosperity, it’s not so clear how it would help set the country on that path.

An investment dealer, more libertarian than neo-con, once asked me, “Why do we need any government?”

“Well,” I said, “let’s start with traffic lights.”

Bill Morneau isn’t one of those run-of-the-mill executives who believe that the best thing that government can do for business is to get out of the way. He appreciates the countless reasons that government is needed to grow the economy, especially in Canada, even while fulfilling its obligation to redistribute the nation’s wealth. And that works best, he knows, when the public sector works in partnership — sorry, has a relationship — with the private sector for their mutual benefit, which is why he’s so proud of establishing the Canada Infrastructure Bank.

Liberals understand that. Conservatives understand that. Even most New Democrats, particularly in office, understand that. The people who generally don’t get it are Morneau’s business friends. They sit in their clubs, sipping their own bathwater from crystal goblets, railing against the taxes, the regulations, the waste, the scandals, the idiocy, as though CEOs aren’t just another vested interest group and as if they never make stupid investments, flawed predictions, or short-sighted decisions based on quarterly results and bonus packages.

All provinces, cities, and towns have their business elites, of course, but Morneau’s story is primarily about Toronto, with its concentration of banks, head offices, and wealth. Nowhere is the systemic disconnect between commerce and politics more apparent than in the contrast between Toronto and Ottawa: they’re not just different cities, they’re different cultures. Most of the CEOs in the big city have a more sophisticated knowledge of French wines than of Canadian government, and if Justin Trudeau ever came within ten paces of them, he’d be shot by the media for corruption.

So Bay Street is constantly looking for a champion in Ottawa and is constantly foiled. Robert Winters lost to Pierre Trudeau. John Turner resigned as finance minister. Donald Macdonald lacked the royal jelly. Michael Wilson was kneecapped by Brian Mulroney. John Turner was propped up and sent back into battle, only to oppose free trade and stagger back to his corner table at the York Club. Paul Martin, fired by Jean Chrétien, proved a dud as prime minister. Mark Carney went to London and came home brainwashed by the greens.

Bill Morneau doesn’t deliver on the promise he makes at the start of his book to explain why so many things don’t work on Parliament Hill. Instead, he prefers to report home with news from the front that’s even worse than his friends suspect: Trudeau is just a performer, the PMO is brain-dead, the ministers are spendthrifts, Ottawa doesn’t give a damn about growing the economic pie, yada, yada, yada. Which is more shameful than an inadequate explanation. It’s a lost opportunity.

Morneau devotes the last four chapters of his book to the importance of everyone pulling together — the federal and provincial governments, the public and private sectors, all parties, all interest groups — to put Canada on the path to prosperity. We must set aside our “trivial concerns and turf wars in times of major threats.” We must not insult the Americans. We must keep talking to the Chinese. In particular, government will need business, and business will need government, to meet the challenges of infrastructure, energy transition, research and technology, health care, immigration, and productivity.

What he neglects to explain is how these relationships will be advanced by walking away from an important seat of power, shitting in public on the colleagues you’ve left behind to do the heavy lifting, and reducing the complexities of managing government to a matter of personalities. For those who take from Bill Morneau’s book the belief that getting rid of Justin Trudeau will cure the nation’s ills — well, good luck with Prime Minister Pierre Poilievre.

Ron Graham is an award-winning journalist and the author of The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight, and the Fight for Canada.

Related Letters and Responses

Joel Henderson Gatineau, Quebec

Walter Ross Toronto

@JohnDelacourt via Twitter

Joe Martin Toronto

@Thomas_Chanzy via Twitter