Recently, Paul Krugman, the Nobel laureate and New York Times opinion writer, took a break from questions of global trade and inflation and devoted one of his columns to Denis Villeneuve’s film Dune. It was not just that he loved the movie; he identified with its project. “Good science fiction involves building imaginary worlds that are different from the world we know,” he wrote, “but in interesting ways that relate to the attempt to understand why society is the way it is.” In numerous other columns, Krugman has shown how economists and social scientists do the same thing.

Of course, historians can be world builders too, as they recreate and interpret past societies in interesting ways. Based at McGill University, the Cundill History Prize has been given annually since 2008 to honour the ones who do that type of work best — with big, serious histories written in English. Out of some 300 titles, the international jury for this year’s prize narrowed the list to three finalists, who, each in her own way, invite readers to visit worlds different than the ones they already know.

Hear the phrase “Mongol horde” and you may conjure up a scene from Conan the Barbarian, with skulls being stacked up in a looted city as the weeping women and children are hauled away. But Marie Favereau, who teaches at Paris Nanterre University, explains that the word for “horde” in nearly every European language is based on the Mongolian word orda, which denotes a type of government: a flexible regime rather than a rampaging mob.

Favereau sets out to convince us that the Mongols who ruled the vast Eurasian steppes from China to the Adriatic were masters of governance, tolerant of their diverse subjects’ customs, and inclined to compromise and diplomacy. Even at the height of their power, they remained nomadic, and it is Favereau’s second goal to convince readers that such empires are as real as sedentary ones defined by agriculture and walled cities. Her overarching goal, though, is to show how “the Horde changed the world.”

The Horde begins with Chinggis Khan (commonly spelled Genghis). Across the Eurasian steppes, there were many nomadic groups, generically called the Felt‑Walled Tents, before Chinggis. His distinction, beginning about 1206, was to unify nearly all of them under his leadership. This accomplishment did involve some skull stacking, but it testified even more to an ability to make subjected peoples full members of a rapidly expanding state. By Chinggis’s death in 1227, his authority extended from China to the Tigris-Euphrates basin, the Volga River watershed, and Ukraine. His family line, the “golden lineage,” would long remain the one legitimate source of leadership within the Mongol Empire.

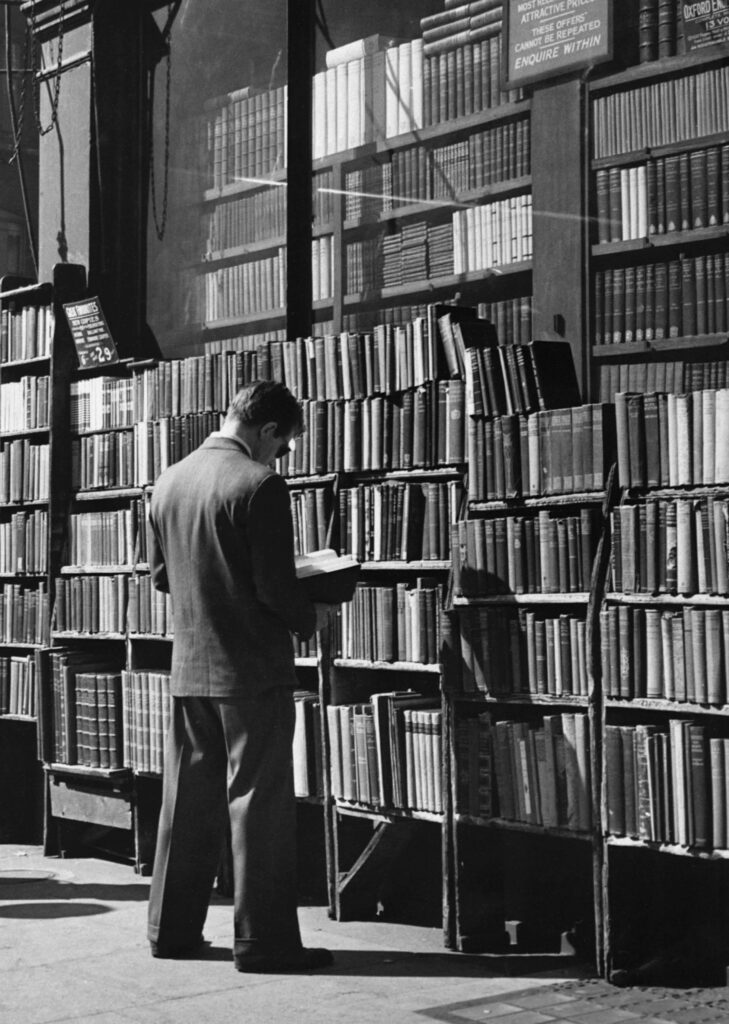

They came from some 300 titles.

Hulton Deutsch, 1951; Corbis Historical

In the vastness of Eurasia, rivalries within the golden lineage were dealt with mostly by separation. When Chinggis’s son Jochi grew restive, for instance, he established his own autonomous orda in the west, while continuing to acknowledge Chinggis’s chosen heir in the central empire. Meanwhile, Chinggis’s grandson Qubilai, the Kublai Khan of Xanadu, made himself emperor of China (though Favereau seems to find him too urban and sedentary to be a true Mongol). Jochi, like his father, died in 1227, but his orda — covering the steppes and reaching far into Europe, Central Asia, and Russia — endured for nearly three hundred years.

Even at its height, the Jochid regime — the Horde of the book’s title — was constantly on the move, shifting its herds endlessly from one grazing ground to another. Favereau vividly describes how an elaborately laid‑out tent city, sometimes housing tens of thousands, could be formed almost instantly — and as quickly dismantled. Although it had no permanent settlements and farmlands, the Horde was an advanced civilization as well as a formidable military power. Its leaders, all literate, ran a well-organized communications network that kept its far-flung population in constant touch. They maintained embassies among their neighbours. Their census and tax registers were as sophisticated as any in the world. Within the limits of what they could carry with them, they lived richly and well. “Mongols themselves,” Favereau writes, “considered sedentary residences less comfortable than their tents, which were warmer, soft, and more intimate.”

Precisely because they were highly mobile, the Mongols had little wish to displace or assimilate those they brought under their rule. Qubilai became a Buddhist, Jochi’s son Berke a Muslim; the ordas tolerated animists, Nestorians, and Orthodox Christians. They encouraged subjects who farmed, harvested furs, produced goods, paid taxes, and engaged in trade. Indeed, it was trade that was the Mongols’ prevailing interest. The Silk Road, which carried much more than silk, ran almost entirely through their territories. Their domination, in fact, provided a rare opportunity for travellers like Marco Polo, from Italy, and Ibn Battuta, from Morocco, who could dare to travel to China and get safely back.

Favereau argues the Mongol Empire, despite its world-building successes, remains underappreciated because settled civilizations have been unable or unwilling to acknowledge that nomadic ones are as real and historical as their own. While the struggle against “the Tatar yoke” is one of the foundational myths of the Russian people, for example, Favereau describes how Muscovite society largely evolved under centuries of Jochid rule and tutelage. (It’s also worth noting that Xi Jinping’s China furiously denies that Chinggis deserves any scholarly attention, as Favereau recently discussed in the Globe and Mail.)

Unity within and among the various Mongol regimes began to unravel in the fifteenth century, as loyalty to Chinggis’s far-stretched lineage eroded. As khans began to kill all their relatives who might become rivals, and as assassination became the favoured route to power, a governing structure dependent on compromise and consensus eroded. The steppe nomads lived on, but Mongol rule gave way to new empires and economies.

Reading The Horde is like immersing oneself in a sprawling epic, as the Jochids, the Ilkhanids, the Khwarezmian Empire, and the Qipchaq Khanate — names long peripheral to Western histories — struggle for control of immense territories. By comparison, Blood on the River, Marjoleine Kars’s account of the Berbice Revolt of 1763–64, is more like a report of war from a forgotten outpost at the far end of the universe.

Berbice (pronounced Ber-BEESE, more or less) certainly feels as if it’s on another planet. Named after a river in what is now Guyana, it was a Dutch colony, where 350 Europeans held 5,000 enslaved Africans on small, undercapitalized, and not very profitable plantations. One Sunday in February 1763, a handful of them rose up, killing or driving out the heeren, or masters, without much difficulty. After several skirmishes, the surviving Europeans fled downriver, and in a few days the rebels, under a leader named Coffij, had taken almost all of Berbice. Situated so far from anywhere that no one came to confront them for many months, the rebels largely controlled the entire colony, with its 135 estates along 240 kilometres of river frontage, for much of 1763, before their freedom ended badly and bloodily, as did almost every slave revolt in the Americas.

Kars, who teaches at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, has the reports from the Dutch governor who held out near the coast, and she is the first person in 250 years to read the nine hundred transcripts of the interrogations that preceded the beheadings, tortures, and hangings carried out during the military reoccupation of Berbice. From the official reports, she follows the progress of the rebellion and its suppression. From the interrogations, she seeks to tease out the hopes and motivations of the slaves who revolted and those who tried to remain uninvolved.

The records do not reveal the spark for the rebellion, except to show it erupted simultaneously on several plantations, just as the dry season made it easier to move through the forests. Nor do they explicitly say why many labourers refused to join the uprising, even after the masters fled, despite brutal retribution and coercion from the armed rebels. Even the aspirations and basic biographies of the leaders remain elusive. “We do not know, for instance, how old he was or whether he was a husband or a father,” Kars says of Coffij. The rebels did write to the Dutch that they had not received justice, that they deserved better food, and that abusive masters were at fault. But they did not speak of “freedom.”

At the height of his power, Coffij offered the governor a deal. The Dutch could have half the colony, he said, and the rebels would hold no grievance. The Africans would keep the other half, and all would go back to the sugar trade. Kars suspects Coffij was acculturated enough to accept the mercantile logic of the slave trade, though the African states from which the slaves had been brought were all ranked societies where forced labour was hardly unknown. Soon after he made his offer, Coffij was overthrown by his fellow rebels, who went on to fight viciously with one another. Finally, a regiment arrived from Europe, and, with Indigenous forces pinning the rebels to the plantations, it crushed the rebellion and restored a grim status quo ante.

The planters’ court that tried the surviving slaves took no interest in questions of motive or belief; it sought only to identify who should die quickly or slowly and who could be returned to bondage. And Kars, for her part, depends too much on her primary sources, leaving her unable to really push questions of motive. Instead, she is forced to speculate, drawing often on comparisons with the Thirteen Colonies, though rebel-controlled Berbice was a satellite of Africa, not of the nascent United States. More attention to transatlantic contexts might have been enlightening. But Blood on the River does bring one very significant and largely unstudied site of the endless war of slavers and enslaved into the light.

Rebecca Clifford, a Queen’s graduate who teaches at Durham University, in England, is the lone Canadian among this year’s Cundill finalists, and her book Survivors is insistently contemporary. Clifford focuses on Jewish children, born between 1935 and 1945, who survived the Holocaust and have lived with it ever since. The result is at once an oral history based on extensive interviews and a consideration of how postwar efforts to treat “displaced persons” or “war orphans” (they only became “survivors” later) transformed child psychiatry and the understanding of memory itself.

Clifford carefully listens to and contextualizes the statements of many child survivors. (What would be oral history for others, she notes, is “testimony” or “witness” for them, as if in a judicial process.) Almost everywhere, she finds that past attempts to help them, no matter how well intentioned, often caused new suffering. Those who feared children had been irreparably damaged did not necessarily recognize the skill and persistence with which they asserted their own agency. Those most successful in helping survivors adapt sometimes denied their right to mourn. Those who sought to reconnect hidden children with family sometimes had to tear them from the only homes they had known. Those who counselled children that it was best to forget took away the only past they had. And adoptive parents who thought it best to give young survivors new names and memories left them with only nightmares of the previous ones.

Investigators documenting the Holocaust sought factual information that brought home to child survivors how little they actually knew of themselves. Sympathetic counsellors, in trying to reinforce fragmentary images the children retained, occasionally demanded invented memories. Children who had been separated from parents and hidden with strangers for years even heard — from those who lived through the camps — that they were not survivors at all, just the “lucky” ones.

Clifford leads readers through this history of pain and incomprehension with the utmost sensitivity, never making a generalization without qualifying it. She writes that into the 1970s, the Holocaust remained under-examined or avoided, while quickly noting all the exceptions to that rule. She then notes that Holocaust literature is now so vast that no scholar can keep up with it, while demonstrating how much can still be learned.

One of Clifford’s subjects is memory itself and the way it is socially constructed. As young people begin to develop memories, trusted adults and companions give them clues to what is memorable and how to “compose” accounts of the past. Torn from the normal conditions in which memories take root, child survivors of the Holocaust were left without their own histories as they strove to construct a livable present.

Rebecca Clifford writes that hers “is a book about the history of living after, and living with, a childhood marked by chaos.” And while the Holocaust is an unparalleled event, its aftermath has lessons for historians of other eras.

Marie Favereau mentions in passing how one orda, seeking an alliance, brought its neighbours gifts: “horses and camels, buffaloes and girls.” Marjoleine Kars cites a young woman, Simba, telling her interrogators of the baby son killed in her arms by the rebel leaders; she also relates the experience of Georgina George, who saw the head of her father, a planter, go up on a spike and then was, in Kars’s too prim phrase, “wed” to the rebel chief Coffij. Clifford’s work reminds us to consider what memories, what history, a multitude of young survivors — whether Mongol, African, or Dutch — would have lived with or constructed.

The finalists for the 2021 Cundill History Prize are so different in subject, in style, in method, even in quality, that I wondered if they were evidence of disagreement and compromise among the jurors. In any case, on December 2, 2021, the jury chair, Michael Ignatieff, declared that “we disagreed very little” in coming to a unanimous verdict. He presented the prize to Marjoleine Kars, for Blood on the River.

Christopher Moore is a historian in Toronto.