Any attempt at a widescreen portrayal of Canadian history is a risky undertaking these days. Toppled statues, heartfelt apologies, angry assertions of neglect, outraged counterclaims: since the turn of the century, this country’s past has become a battleground as various groups struggle to make their version of it the dominant story.

University-based historians have frequently exacerbated the conflicts, both by abandoning narrative history in favour of a more analytic and micro-community approach and by treating their discipline as a site of intellectual warfare, where they can recklessly trash the work of their predecessors. As Margaret MacMillan has pointed out, “We can learn from history, but we also deceive ourselves when we selectively take evidence from the past to justify what we have already made up our minds to do.”

So the non-academics have been left with the challenge of writing for a general audience — and the task of achieving that elusive quality of “balance.” Today’s popular historians must include far more voices than were captured in such standard Eurocentric volumes as Arthur Lower’s Colony to Nation, from 1946, without ditching a factual framework. As these authors try to pin the richness and complexity of earlier times onto the page, they must also generate a momentum that will capture the reader. The goal is insight into how this country has evolved. But how can they avoid the dead weight of on‑the-one-hand, on-the-other-hand prose?

Stephen R. Bown outlines the problem of shaping a balanced narrative in the introduction to Dominion, his account of the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway — among the most exceptional megaprojects of all time. He dives straight into the trenches with his very first paragraph: “The CPR was a great triumph of imagination, vision, politics and engineering, as well as a horrible environmental and social tragedy.” While the railway allowed “titanic economic expansion,” it also enabled “repression of the land’s original inhabitants and the exploitation of thousands of labourers.” Bown pushes on. A reader who wants to understand the CPR “must keep that dichotomy in mind.”

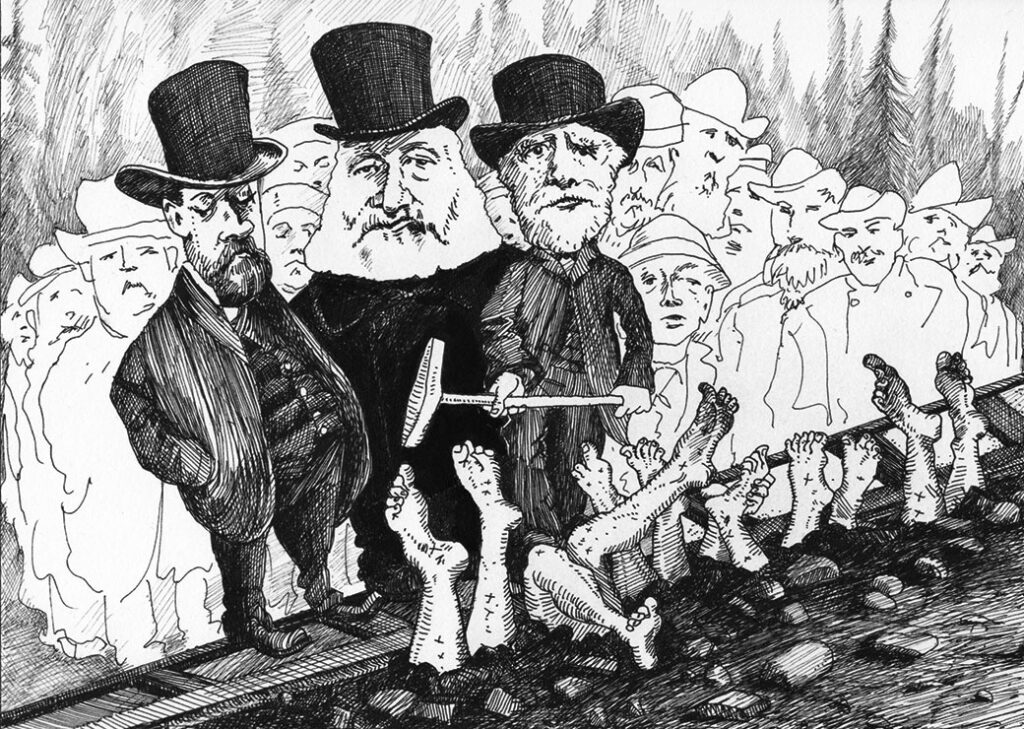

A crowning achievement for some was a living inferno for countless others.

Silas Kaufman (After Gustave Doré)

We are clearly not in Pierre Berton territory here: no more soaring triumphalism of sweaty men conquering muskeg and mountains. Rather, Bown interrupts descriptions of breathtaking exploits with sections on the misery caused by those steel tracks punching across the continent. “The CPR’s conceptualization and construction made possible a new country,” he declares, “but it came at a terrible price for some.”

Bown has written extensively on the history of exploration, science, and ideas. In 2020, he published The Company: The Rise and Fall of the Hudson’s Bay Empire, an excellent chronicle that showcased a thorough knowledge of pre-Confederation Canada. He begins this book in an unexpected location — Victoria in 1870 — and describes the precarious position of an isolated and indebted British colony that was being drawn inexorably into California’s economy. This frame of reference allows him to explore the geographic barriers to any east–west transportation links, as well as the vicious conflicts between Chilcotin warriors and land-hungry surveyors. John A. Macdonald, the most significant politician in any account of late nineteenth-century Canada, appears only after the author has given us a panoramic view of the Province of Canada (as Quebec and Ontario were known in the 1850s and early 1860s). This was a place with “no cultural cohesion, shared history, naturally linked economic interests or mutual future dreams.” Its slide into an American embrace seemed, like Victoria’s, inevitable. “Nearly all the political actions that drove Macdonald’s career,” Bown argues, “can be seen as passionate opposition to American expansion.”

Bown sketches Macdonald’s character and muses, “Given all his foibles, it makes one wonder whether he and others like him were the great people history paints them as or whether Macdonald was just one of yesterday’s mediocrities bloated by a century and a half of unearned credit to suit a popular narrative of nation making.” But Bown does not leave us hanging. “If you consider the creation of Canada to have any merit,” he argues, “then he was undoubtedly the right person at the right time.” Macdonald established Confederation, negotiated the transfer of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s territory to the new dominion, and began to dream of a transcontinental railway to coerce British Columbia to join with Canada.

The preliminary steps to getting that railway built are outlined clearly: Louis Riel’s doomed leadership of the Métis resistance to the arrival of surveyors; Sandford Fleming and George Grant’s 1872 expedition to map out a route; Macdonald’s machinations to finance his dream. There is an interesting chapter on the importance of Alfred Nobel’s invention of dynamite, “a catalyst for the grandiose dreams” of modern infrastructure throughout the British Empire.

The second part of Dominion does not steam straight into the monumental task of laying thousands of kilometres of rail across bogs, rivers, and mountains. Instead, Bown gives more thorough attention than previous popular historians to the Indigenous people across whose lands the trains would travel. During the fur trade era, bands had dominated the landscape; by the 1860s, the prairies were characterized by disease, rapid change, and economic disruption. Once-proud nations were disintegrating. While Washington pursued a murderous policy of extermination, Ottawa muddled along with a combination of paternalism (imposed through the numbered treaties) and indifference to appalling hardships. Again, Bown does not rush to judgment: “The question of whether the treaties were good or not has no answer.” Nobody could foresee the future, he points out, and at the time there appeared to be no alternative. “To not sign would have soon meant starvation and continuous warfare.” But as the Indigenous population shrank due to starvation, disease, and death, Ottawa’s failure to respond with any hint of humanity “was odious.”

Two-thirds of the way through Dominion, the author finally embarks on the massive business of actually constructing the railroad: the hideous task of identifying a feasible route, the endless bribery and mendacity involved in financing it, the frenzy to build as fast as possible, regardless of how many workers were injured or killed. In doing so, Bown never lets the reader lose sight of, for example, the Shuswap-Secwépemc guides who enabled Major Albert Bowman Rogers to find the pass through the Rockies that would bear his name. And Bown devotes several pages to Dukesang Wong, one of the thousands of Chinese workers who crossed the Pacific in search of opportunity — and one of the few who left accounts of their misery. “My soul cries out,” begins one of Wong’s poignant passages.

Bown’s story is only partly about the CPR; as his subtitle makes plain, it is also about the rise of Canada. Toward the end, he abandons his detachment to clarify his abhorrence of how Indigenous people were regarded once the treaties were signed. “There is no way to describe what happened other than as a betrayal — a legal betrayal, a moral betrayal and a technical betrayal that was and remains a stain upon the nation’s honour,” he writes. “The litany of downright disgusting conduct, including the sexual exploitation of women and girls by immoral, abusive and sadistic politically appointed agents, suggests a staggering level of incompetence or a nearly psychopathic lack of empathy.”

Of course, the railway got built: the last spike was hammered in November 1885, allowing Canada to develop a national economy. Bown retreats to lofty observations as he draws his book to a close. “It’s up to us to do what we want with knowledge of past events,” he argues. “History isn’t about good or bad but about what happened and, just as importantly, how and why.” Macdonald’s overriding ambition to establish a new political dominion separate from the United States blinded him to the unintended but cruel consequences of achieving it.

Previous accounts of Macdonald’s dream to tie the country together with a steel spine have relied on machismo and high drama to build momentum. Bown has written a more sober and inclusive analysis of the mammoth effort required to realize the CPR. Dominion is enlivened by vivid portraits of characters like Judge Matthew Baillie Begbie, Jerry Potts, Crowfoot, and Sir William Van Horne, and it raises the kind of questions that we should all be asking today. At a time when too many writers and readers are turning away from historical non-fiction, Dominion reminds us that Canadian history is nothing to be afraid of. Bown gives us a clear picture of the winners and losers in one particularly consequential episode.

Charlotte Gray is the author of numerous books, including Flint & Feather: The Life and Times of E. Pauline Johnson, Tekahionwake.