Note: Due to an imposition mistake on press, page 14 of this review was incorrectly printed in the January/February issue. (The online and tablet versions were unaffected.) The magazine regrets the error and will include a reprinted version of the review with physical copies of the March 2024 issue.

There is no court of appeal for book prizes. A jury’s decision is final — and not just about who wins. With new members every year, and not much in the way of binding precedent to guide them, juries have a lot of latitude as to what kinds of books their prizes will honour. The Pulitzer Prizes have separate honours for history and biography and non-fiction, and from the lists of finalists it’s not always easy to tell how the juries match the books to the categories. In Canada, jurors for awards like the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing and the Donner Prize, for best public policy book, have sometimes stretched the boundaries to recognize deserving titles. Or so it appears from the outside.

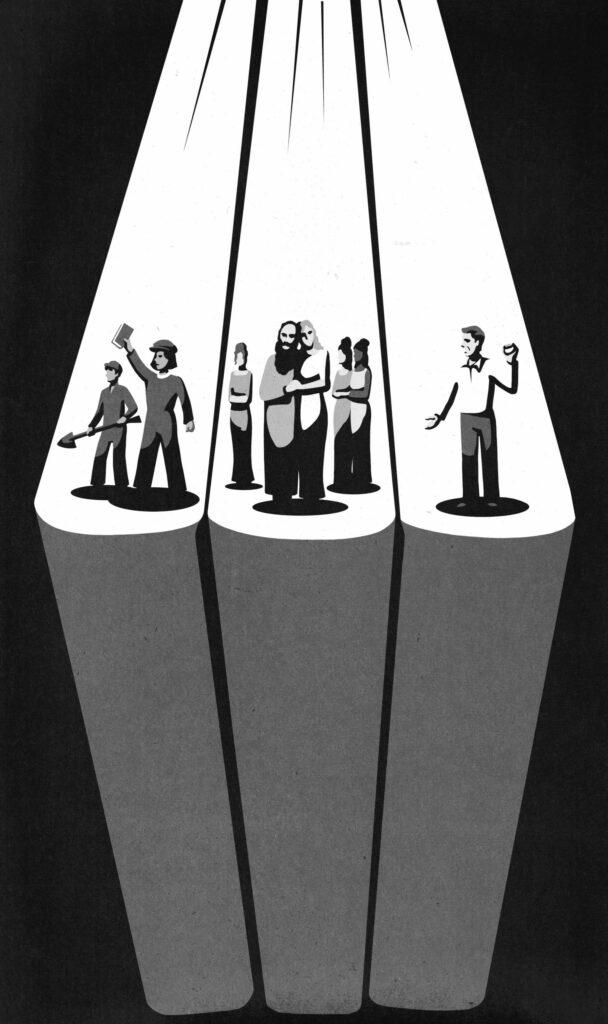

For the Cundill History Prize, one pattern has long seemed predictable: a predilection for big books. They were not always thousand-pagers, but a year’s short list usually filled a significant chunk of shelf space. For 2023, however, even the longest books have barely 300 pages. They almost resemble short story collections more than world-building historical epics. And they spark reflections on what constitutes a candidate for the year’s best history book in English.

Tania Branigan’s Red Memory, which was announced in Montreal on November 8, 2023, as the latest winner to take the $75,000 (U.S.) Cundill purse, considers China’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution less through its actual events than through profiles of aging and traumatized survivors. Branigan found her inspiration in a Beijing exhibition, not completely banned but not exactly authorized, called Chinese Historical Figures: 1966–76. It included a series of close‑up portraits of individuals, famous and unknown, who “had played a part in this madness, as victim or perpetrator; often both.” The artist, Xu Weixin, was eight when he joined the Cultural Revolution by denouncing his teacher, Miss Liu, as a “class enemy.” Her life was destroyed, and Xu went on to explore his role in that throughout his artistic career.

Branigan, raised in London by a British father and a Thai Chinese mother, was the Guardian’s correspondent in China from 2008 to 2015. “I began to sense the Cultural Revolution in almost every subject I covered,” she writes in her prologue. “It was a silence, a space, that made sense of everything existing above or around it.” She decided to seek out Xu’s subjects and others like them.

Among the best history books in English?

M.G.C.

In effect, everyone Branigan met and talked with was another Xu Weixin — another aging participant struggling to cope with an overwhelming experience no one in China is supposed to discuss. Wang Jingyao, a historian, showed Branigan a secret shrine, filled with mementoes of his wife, known as Teacher Bian, who was battered to death by her own students. Later, some of those former students talked to Branigan in passive evasions, at once confession and exculpation, about “the 5 August incident” and how difficult its complexities were for them.

In Shantou, in Guangdong province, Branigan visited a small museum and memorial park for victims of the Cultural Revolution. There, Peng Qi’an, a civic official who narrowly escaped execution, had preserved the names of his unlucky comrades on a hillside where their bodies were dumped. But when Branigan attempted to enter the museum, a sign was quickly hung on the door to explain it was closed —“for safety maintenance.” Undercover cops photographed her as she walked away.

At the Beijing Central Conservatory of Music, the composer Wang Xilin told Branigan how he discovered his interest in Western classical music and studied under Lu Hongen, who conducted the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra before being executed. Wang saved himself, in part, by composing “model operas” in the Communist Party’s approved style. Eventually he was able to return to his own musical preferences, only to offend officials in 1999: his honesty —“a compulsion, not a decision”— led him to comment publicly that Communism had been “abandoned.”

Above all, most of Branigan’s subjects spoke of the horrors of being caught “on the wrong side of history.” For them, the Cultural Revolution often meant participating in the murder of loved ones, destroying careers, shattering cherished institutions, and then being “struggled against” themselves — humiliated, beaten, tortured, and frequently sent into years of exile, poverty, and hard labour in rural China.

Zhou Jiayu, however, defended the dream of a permanent levelling of rich and poor, weak and powerful, even while he acknowledged that the Cultural Revolution wrecked his life and many others. In retirement, Zhou remained poor, radical, and contemptuous of the “leadership of capitalist running dogs.” He argued endlessly with his old Red Guard companion Zheng Zhisheng. Once dubbed the “Corpse Master,” responsible for hauling away the bodies of Red Guards’ victims, Zheng later ran a chemicals business. He conformed and did well, even as he grudgingly admired Zhou’s continued idealism.

Branigan let her interviewees bring out the pain, anger, regret, and confusion with which the Cultural Revolution had burdened them. The trauma and dislocation the movement helped embed in Chinese life seems to interest her more than its causes or its chronology. “Maoism,” she writes, “had destroyed the moral architecture that existed, however flawed, and attempted to replace it with hastily erected constructions . . . which were then razed too.” Everyone was a victim.

Mao Zedong remained above criticism during the Cultural Revolution, but few others did. Party members accused of sliding into bureaucratic complacency were a frequent target: the most loyal followers could become the most hated. The mob violence of young Red Guards lasted only a couple of years before they themselves were subdued by the People’s Liberation Army. Millions continued to be condemned to internal exile, starvation, and brutality. The father of Xi Jinping, the current president of China, was among the purged party officials.

It is impossible to understand China today without understanding the Cultural Revolution, Branigan writes. But no one understands the Cultural Revolution. The Chinese with whom she spent time lived with trauma, not just from the events themselves but also from the impossibility of coping with the memories, in a country where past crises are both omnipresent and never to be spoken of. Observing a conference of psychotherapists, Branigan found their field was booming, even as many of the practitioners suffered the same nightmares as those they treated.

In a country where official dogma frequently reverses itself but never admits to error, few are permitted to speak freely about history or its meanings. Having asked people about the Cultural Revolution, Branigan portrays China as an amnesiac nation, plagued by traumatic memories that can be neither admitted nor denied, able to speak out only in platitudes that the latest leadership doctrines will tolerate. In one chapter, she profiles impersonators who performed as Chairman Mao, Zhou Enlai, and even Lin Biao, the arch-villain of the Cultural Revolution, to entertain crowds at nightclubs and business openings. In China, she suggests, historical awareness is rarely permitted to go much further.

Red Memory is a haunting, troubling book. But is it history? A British reporter, Branigan was on assignment in China. She gathered the material for this book entirely by journalistic practices and perspectives. She interviewed and transcribed and observed. As journalism, this is heroic work, given the mass surveillance and deep hostility to both reporters and foreigners that typifies China, particularly during Xi’s regime. If Red Memory were nominated for a journalism or other non-fiction prize, my admiration would be unbounded.

It remains journalism, however, built from the best practices of that field, rather than history. Focusing on survivors’ memories, Branigan barely attempts a timeline of the Cultural Revolution, and she draws on no archival collections beyond the personal materials of her interviewees. In the face of the repression, censorship, and happy-talk propaganda that pervade society under Xi, a journalist gathering personal testimony makes a vital contribution to the understanding of China. Yet as Ian Buruma recently wrote in The New Yorker, Cultural Revolution history is a thriving topic among sinologists, both outside China and among “underground historians” working around the fringes of Xi’s official version. Might future Cundill jurors consider some of them?

Trained at Harvard and Princeton and now a professor at the University of London, Kate Cooper is most certainly a historian. And her research subjects sound “historical” beyond question: the Roman Empire of the fourth and fifth centuries, late Roman and early Christian ideas on marriage and gender relations, and the theologian and philosopher known to us as Saint Augustine.

Cooper’s Cundill finalist, Queens of a Fallen World, is a deeply imaginative and unconventional work. Cooper comes to Augustine’s life and thought indirectly, through an attempt to reimagine the lives and hopes of four women, two of whom have no recorded names and are known only from a line or two each in Augustine’s autobiographical Confessions. With so little information, Cooper dubs one of the anonymous women Tacita, Latin for “the silent one.” She calls the other Una, simply meaning “someone.”

Cooper focuses on the period leading up to and following Augustine’s thirtieth birthday. His mother, Monnica, has found him a fiancée in Tacita. This plan threatens disaster for Una, probably a family slave, who has been his concubine for a decade. (The fourth woman, more remote from the story, is Justina, the wife of the embattled emperor Valentinian.)

The popular image of Saint Augustine’s ideas on marriage, to the extent there is one, is based on his alleged quip, “Lord, make me chaste. But not yet.” The line typecasts him as a familiar Christian character: a louche young man until a miracle brings God into his heart, after which he adopts views on marriage and monogamy we might now associate with a modern Southern Baptist.

Cooper engages Una and Tacita to demolish this image of Augustine. In the aftermath of Emperor Constantine’s decision to make Christianity the imperial religion, even Christians of the empire still mostly stuck to traditional Roman ideas of marriage and sexual relations. For them, marriage almost exclusively concerned household alliances and security of property. Around 380, Roman citizens, including Christians like Augustine’s family, were married not for love but for status and property. Before and during marriage, men found it normal to keep concubines and to have unrestrained sexual access to servants and slaves like Una. The law’s main support of the marriage bond was to make it almost impossible to legitimize children born to concubines.

In accepted Roman fashion, young Augustine kept a mistress and fathered a son with her. At the same time, he was striving to make his way in official Roman circles. When he had risen enough to make a prestigious alliance feasible, Monnica arranged his engagement to Tacita, a well-born girl of just ten years old.

At this point, Augustine broke with convention. He dismissed Una and never saw her again. But he also called off his engagement to Tacita. He abandoned his bright future in officialdom and politics to join a Christian community in North Africa, where he committed himself to celibacy and philosophy for the remainder of his life.

Cooper’s argument — after a long contemplation of Augustine’s interactions with his mother, his lover, and his fiancée — is that Augustine was not following the now familiar Christian path of conversion. He did not simply put aside sex and the material world in favour of chastity and prayer. Rather, he invented a new theology of marriage. As Cooper puts it, Augustine’s sin “was not sleeping with his concubine. It was casting her away.”

Teasing out meaning from brief asides in Confessions and longer arguments in Augustine’s philosophical works, Cooper proposes that Augustine had come to believe that his real marriage — his only marriage, though legally not a marriage at all — was with Una, with whom he had shared a companionable, even tender relationship for years. To enter into a legal marriage with someone else would be equivalent to adultery. By rejecting the Roman view of matrimony, Augustine laid the groundwork for a different conception of wedlock, defined by affection, companionship, and sexual fidelity. His personal experience would influence the course of Christian theology and Western thought for more than a millennium.

Queens of a Fallen World offers a significant interpretation of Saint Augustine and the cultural transformation of the late classical world, based on a wide reading of Roman sources. It does not need to defend or justify its status as “history.” But what brought the book to the attention of the Cundill jurors may have been how Cooper presents her story.

Again, the big historical argument of Queens of a Fallen World concerns the birth of the Augustinian understanding of marriage. A more conventional approach might have made this case from Augustine’s own writings without much attention to the two anonymous women. Instead, Cooper builds her story around them, letting the biographical details of their relationships lead her to new insights about the intimate sources of Augustine’s theological revolution.

The Cundill jury, in choosing this book along with Branigan’s Red Memory, seems to have acknowledged a great wave of writing grounded in personal engagement that has been sweeping through all forms of twenty-first-century non-fiction, not just memoir. Like Branigan, Cooper says little about herself directly. But her devotion to these barely documented women and her fury at misogyny — which, in her portrait of Ambrose, a power-hungry bishop and mentor to Augustine, she presents as an ahistoric and eternal trait — testify to her willingness to engage personally with her subjects in a way that would have been rare in historical scholarship until recently.

James Morton Turner’s Charged lacks the vivid close‑ups of traumatized old revolutionaries or maltreated women of antiquity found in the other two Cundill finalists. Instead, this is a history of batteries — the type of book a quirky uncle might give his nerdy nephew for Christmas, to go with the science kit from last year. Still, it’s a careful and scrupulously referenced historical account of an important object: where it came from, its evolving influences on society, and where it might be taking us.

Turner opens a few chapters with his personal encounters with battery power, but Charged makes few concessions to current fashions in structure or narrative. Indeed, readers will encounter long paragraphs that start with sentences like “Here are the basic steps in manufacturing a lead-acid battery.” One suspects the Cundill jurors were seduced by how Turner, an environmental historian at Wellesley College, in Massachusetts, was nonetheless able to make his subject come alive. He never lets us forget that, in a world where “technological optimism is ascendant,” weaning the world off fossil fuels “is going to require thinking about a clean energy future from the ground up.” Since electricity is always ephemeral, batteries, including how we design and use them, will determine whether our societies can make that transition successfully.

Early on, Turner introduces readers to the idea of energy quality. We prefer our energy sources to provide “density, storability, portability, and relatively low cost,” he tells us. Throughout the twentieth century, fossil fuels won on nearly every metric of energy quality and fulfilled most of our energy requirements. The lead-acid battery played a supporting role — though a critical one.

Powering ignition systems in millions of cars, trucks, and motorboats, bulky lead-acid batteries helped early gasoline automobiles (with their big fuel tanks) kill off limited-range electric vehicles by about 1920. They provided essential backup for electrical transmission systems as well as power for telegraphs, telephones, and radios. Of course, lead mining and manufacturing can have lethal consequences, especially in the mostly low-income and racially segregated neighbourhoods where battery plants have been concentrated. As regulations mitigated some health concerns, at least in North America, lead-acid batteries became “the most efficiently and highly recycled product in the world.”

Next Turner takes up AA and other dry-cell batteries. Horribly inefficient, they have long appealed to our throwaway culture and mobile lifestyle, powering our flashlights, our portable radios, and many of our toys. A typical single-use battery requires “160 times more energy to manufacture” than it will return during use, Turner tells us. “That makes the carbon footprint of the average single-use battery more than forty times greater than an equivalent amount of electricity generated by a coal-fired power plant.” And though modern AA batteries are not very toxic — especially since the elimination of mercury from their ingredients in the 1980s and early 1990s — billions of them lie in our landfills.

We are now living in the era of the lithium-ion battery, which has made possible the wireless revolution: iPhones, laptops, even hearing aids. It is also giving solar and wind a competitive edge in the twenty-first-century energy-quality sweepstakes. As they increasingly power our cars, trucks, trains, and aircraft — as well as our homes and factories — lithium-ion batteries and their successors could quite possibly make the clean energy transition possible.

As he describes the origins and evolutions of these three battery types, Turner catalogues the enormous challenges and complications inherent in the various technologies. Making the energy transition, he points out, will require a vast amount of new consumption: all those electric vehicles, all those replacement systems for heating and lighting. Making a transition that’s socially just will be doubly difficult, as demonstrated by Turner’s many examples of environmental and health inequities in the evolution of batteries, particularly among poor and marginalized people.

In his conclusion, Turner explores two sides of environmental consciousness that may define the future. Anti-modernism, on one hand, is the conviction that our survival depends on protecting wilderness, limiting population growth, reducing consumption, and generally living simply and with less. Material environmentalism, on the other, accepts that humanity will never give up its stuff but trusts in a carefully planned transition to save the planet without inflicting new forms of poverty or colonial exploitation. Turner sets out the follies of blithe technological utopianism in chilling detail. Even so, he argues that a green transition might just keep the lights on without burning down the planet.

It’s a powerful ending to a sometimes difficult book — and it probably helped convince the Cundill jury that Charged deserved to be among their finalists. No one who thinks seriously about our energy future should neglect either Turner’s warnings or his hopes.

Christopher Moore is a historian in Toronto.