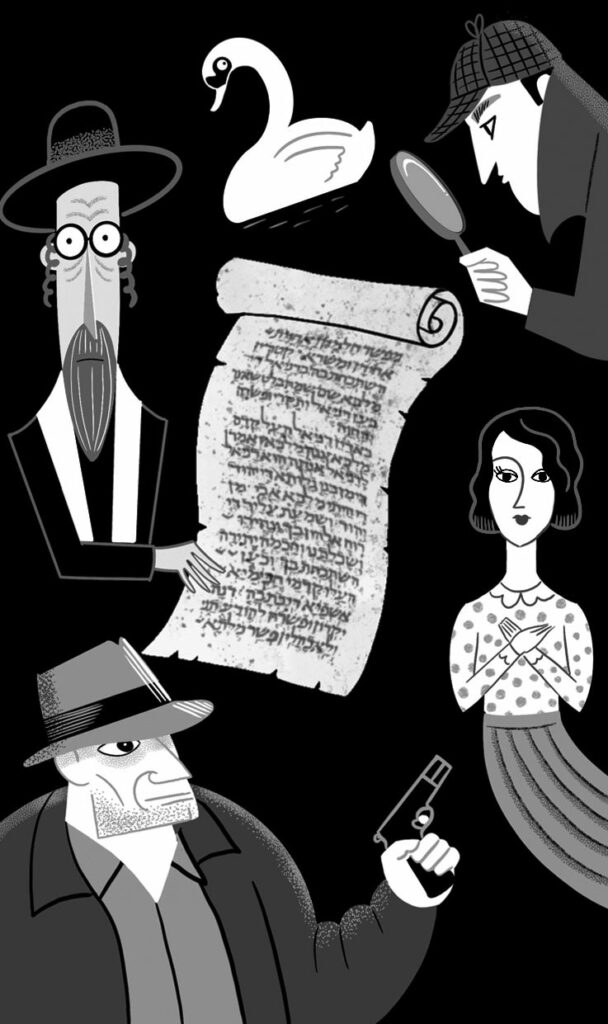

Sherlock, meet Indiana. Indiana, meet Sherlock. In his third novel, Pilgrims of the Upper World, Jamieson Findlay combines Arthur Conan Doyle’s style of zigzagging detective fiction with a fast-paced quest narrative that recalls Raiders of the Lost Ark. Findlay — who lives in Chelsea, Quebec, and won the $10,000 (U.S.) University of New Orleans Lab Prize with this manuscript — offers readers a well-written and surprisingly poignant page-turner.

Set in present-day Geneva, the story follows the middle-aged bookseller Tavish McCaskill. As he lives his quiet life, McCaskill grapples with lingering feelings for his ex-wife, Julie: “Often, when couples split, they become strangers to one another. Not us. So I liked to think.” He can’t stand her arrogant new husband, a neurologist who’s “brusque and unfinished as a new mountain, craggy and sharp-jawed, fault lines everywhere.” And he’s been dealing with recurring nightmares since his teenage daughter died in a car crash twelve years ago. “Saoirse, my sweet girl, my sunrise,” he laments. “Was it going to be like this for the rest of my life?”

McCaskill’s predictable routine changes when Rabbi Zarandok bursts into his shop. McCaskill doesn’t know the old man, who’s “spare as a cornstalk in winter, with the narrow face of an elf and teeth done in shades of ash.” But the old man knows him; in fact, he’s researched McCaskill extensively. Why? The answer lies in a manuscript fragment, some 600 years old. Covered in roughly scrawled Aramaic (“the language Jesus spoke”), it apparently belongs to a long-lost text penned by the kabbalists, an obscure group of medieval Jewish mystics with only one surviving work, the Zohar. Zarandok wants McCaskill, who wrote his master’s thesis on the kabbalists and can read the ancient language, to verify the page’s authenticity.

McCaskill is skeptical but looks it over. At first, it resembles the Zohar: a dialogue between a master and a student about God, the Torah, and the afterlife. However, the presence of a modern mathematical formula — the Schrödinger wave equation — leads the bookseller to conclude it’s a forgery: “Somebody has faked you. It may be Aramaic but it can’t be very old.” Undeterred, Zarandok insists that McCaskill further examine the manuscript overnight and promises to return the next day. He also warns McCaskill to keep the visit a secret: “Do not tell anyone. No wife and no man. Do not show the page.”

A caper filled with colourful characters.

Jamie Bennett

Reluctantly, McCaskill complies. He’s driven as much by a desire to upend his melancholy day-to-day as by his long-standing affinity for the kabbalists, those “wild-brained mystics” who “embodied the unfeigned self, the raw soul.” After several hours translating and retranslating the page, he makes a startling discovery. Ezra Ben‑Emeth, also known as the Rabbi of the Twelve Winds, a sixteenth-century kabbalist who purportedly spoke with the prophets Elijah and Gabriel, may have actually written it. That would make the document priceless, but it still wouldn’t explain the equation. And, anyway, what were the chances that Zarandok had stumbled across such a rare and valuable artifact? “About as good as the chances of me getting my face on the next Swiss stamp.”

The following day, McCaskill eagerly awaits Zarandok, who never shows up. Perturbed, McCaskill searches out the old man’s apartment and finds it deserted. He asks around town; no one knows anything. As the shopkeeper turns detective, he feels invigorated: “No waking up feeling like dead matter, like the long-cold remnants of an exploded star.” After several days, he’s uncovered a tangled network of acquaintances and relics, but he’s no closer to finding the rabbi himself. Matters become further complicated when he runs into a woman curiously resembling his late daughter: “She reminded me so much of Saoirse. It was uncanny. Older than Saoirse had been, but still, that’s what Saoirse would have looked like if . . .”

But she’s not Saoirse. She’s Jaëlle Kodaly, the descendant of a famous mathematician, János Kodaly, from whose archives she claims Zarandok stole an entire manuscript. The twenty-six-year-old consultant, whose eyes resemble “the moist plumes of ink made by a calligrapher’s brush” and who stands “a touch gawky, nerdy-magisterial, like a flamingo,” convinces McCaskill to join forces with her in searching for the alleged thief. Their “wild goose chase” has hardly begun when a mysterious group called the Friends of the Shared Path kidnaps Jaëlle, mails her cut‑off braid to McCaskill, and, convinced the bookseller knows Zarandok’s whereabouts, proposes a trade: the young woman for the rabbi. McCaskill must find Zarandok with the shadowy group watching his every move and Jaëlle’s life hanging in the balance.

After much sleuthing, McCaskill learns that Zarandok has followed the Way of St. James, a pilgrimage route from Geneva to Lake Constance, and he sets off at once. Along the way, he encounters colourful characters. There’s Aaron Franks, for example, a clergyman with a wheelchair and “wayward red hair, ear stud, and massive chest.” There’s Detective Dassvanger, a brash investigator whose “features were coarse and graphite-dark, as if roughed out by a carpenter’s pencil.” In these chapters, Findlay takes readers on a descriptive tour of Switzerland’s scenic locales. Lausanne: “The tilted city.” Schwarzenburg: “A friendly, handsome, old-world village.” Lucerne: “An airbrushed dream of a city, flower-suffused.” Zurich: “Big and boutiquey, metropolis of swans and stained glass, home to the world’s largest this and most silvery that.”

The novel becomes an all-out thriller once McCaskill finds Zarandok, and the unlikely duo team up to confront the Friends of the Shared Path, rescue Jaëlle, and discover the truth of the manuscript’s origin. But the shift is jarring and not entirely satisfying; the gripping mystery gives way to shootouts and dialogue reminiscent of an ’80s Schwarzenegger flick. It’s a timid turn, as though Findlay didn’t trust himself to maintain the reader’s attention with his more deliberate pacing and tone. What’s more, the ending is vague and almost nonsensical: it’s left unclear whether McCaskill is still on earth or if he has ascended to the supernatural “upper world” implied by the title.

Still, the novel succeeds on the strength of its compelling characters and largely thoughtful prose. And the ending does one thing right: it hints at a sequel. If Pilgrims of the Upper World 2 deals with the unanswered questions left by its predecessor, it will be a journey worth taking.

Alexander Sallas can now collect his frequent flyer miles as Dr. Sallas.