There is no accurate figure for the number of books published about the American Civil War, but one estimate puts it at about 57,000, just short of one for each day since the guns were stilled at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, in April 1865. (I read five myself in the first six months of this year, even with no special effort to do so.) As the November election approaches and as the shrill voices south of the border get ever more angry and agitated, we can add a swelling multitude of contemporary books predicting a new civil war in the United States to the mountain of volumes already in print about the nineteenth-century conflict. Certainly the field of civil war studies, whether rendered in uppercase or lowercase letters, is a growth industry.

Even so, the latest work from the University of Virginia historian Alan Taylor — who with two Pulitzer Prizes is a member of an exclusive group that comprises such scholarly giants as Bernard Bailyn, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Richard Hofstadter, Allan Nevins, and Samuel Eliot Morison — stands virtually alone. The qualifier “virtually” is required here because buried in that pile of Civil War books might be a handful of other forgotten volumes, published somewhere by someone, that treat the conflict as a truly continent-wide phenomenon. At any rate, it is unlikely that any of them frame the period as a trio of parallel — at some points, even converging — national struggles with the mastery and sweep that distinguish American Civil Wars. Julian Sher’s The North Star: Canada and the Civil War Plots against Lincoln, which I reviewed in these pages in the January/February issue, dealt with only two-thirds of the giant North American countries, omitting Mexico. Taylor, though, brings the Mexican angle to light with great detail and verve.

But our concern in this magazine is Canada, and in Taylor’s effort “to see our history as continental rather than simply the isolated story of one nation,” the country gets considerable and admirable attention in a volume that usefully reminds readers north of Brownsville, Texas, and south of Houlton, Maine, that the continent of North America is made up of more than the United States. That is not to say that John A. Macdonald figures as prominently as Ulysses S. Grant or Robert E. Lee in Taylor’s book, but he’s in these pages. So too are, among many others, the Toronto Globe founder and political figure George Brown, the abolitionist Alexander Milton Ross, the journalist and politician William McDougall, and the merchant trader Edward Ellice. On a visit to the United States in 1861, Ellice made this astute observation about the citizens of the Union, who were, after all, the good guys: “What a strange race of madmen — only fit for a lunatic asylum — our old, calm, calculating, and sagacious friends in the North . . . have become!” A Canadian visitor might make the same assessment today.

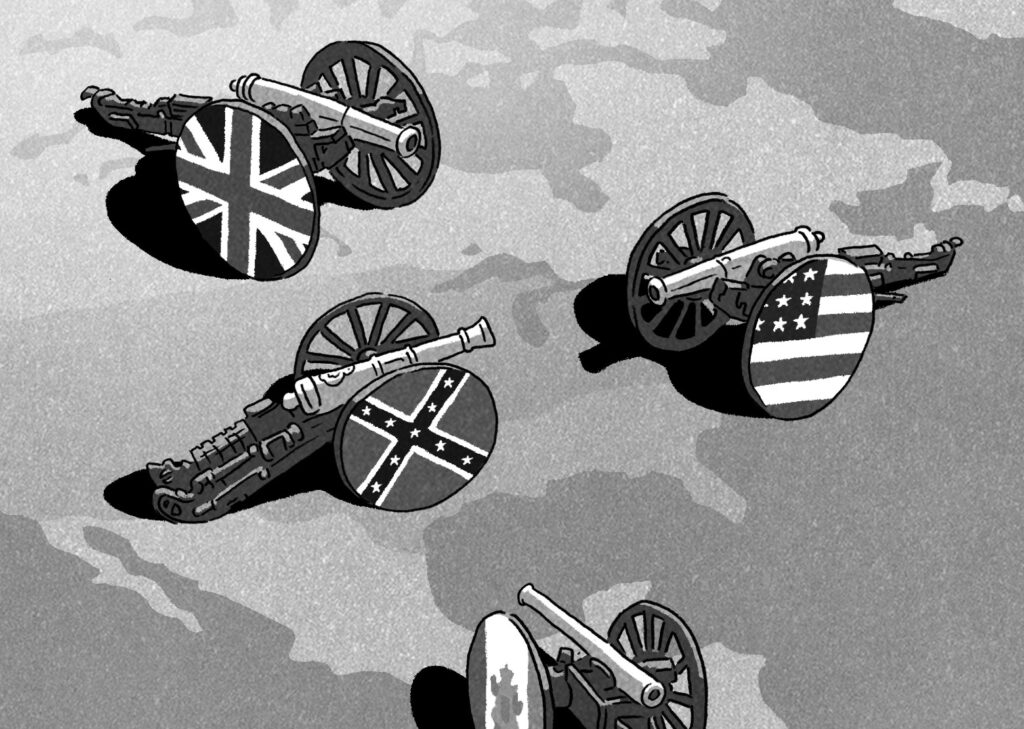

Going beyond the Union and the Confederacy in a sweeping Civil War history.

Tim Bouckley

The differences between Canada and the United States, often unappreciated below the border, were far starker at a time when Toronto and Montreal looked south and saw two countries, not simply one, standing between them and Mexico. But their contrasting characteristics were the least of it. In the period leading up to the Civil War (roughly 1850 to 1861) and while the Confederate States of America and the rump United States were in fratricidal conflict with each other (1861 to 1865), Canada still had real and justifiable worries about being annexed. It was far smaller — in its size, its vision, and, notably, in its internal contradictions and conflicts — than the powers next door.

Back then, Canada was ruled by a monarchy; the two warring countries to the south were governed as republics. Canada’s population was 3.2 million. The Union’s was 19.2 million and the Confederacy’s was 8.7 million, with roughly 4 million of them enslaved. (The Border States of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri, and West Virginia were home to another 3.5 million, roughly 500,000 of whom were not yet emancipated.) The biggest city in Canada was Montreal, with a population of about 40,000, similar to the population of Richmond, Virginia. The biggest city in the Confederacy was New Orleans, more than four times the size of Montreal, and the largest city in the Union was New York, at 813,669 people. But the biggest differences were these: The Canadian swath of the continent no longer tolerated slavery. And for all its diversity in religion and language — and acknowledging that a majority in Canada West was in a consequential power imbalance with a prideful minority in Canada East — Canada was not torn by violent insurrection. “We have our N[orth] American Provinces now united & loyal, and dissatisfied with the United States,” wrote the British home secretary, Lord Palmerston, in 1854. That’s another sound bite for our times.

The absence of slavery from what is now Canada is fairly easily explained. One reason was Britain’s intolerance of the practice, codified in the Slavery Abolition Act, which Parliament passed in 1833 — more than a quarter century before the American Civil War began with the shelling of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. (The U.S. didn’t get around to outlawing slavery until the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution was ratified in 1865, when the seceded states were not yet reconstructed and returned to the Union.) Another reason was modern slavery’s geographical and meteorological incompatibility with Canada, due to its climate and lack of a cotton trade; in the South (in the minds of plantation owners but few others), forced servitude was a necessity. That is why Harriet Tubman and her fellow engineers on the Underground Railroad found Canada a congenial destination for those fleeing slavery. Taylor observes that in 1860, “the monetary value of enslaved people exceeded that of all the nation’s banks, factories, and railroads combined.”

The straw that stirs this bracing drink is, of course, the war that remains the deadliest conflict in U.S. history, and most of the book consists of an account of the causes and progression of the fighting. But in providing readers with an unusual view of the war, Taylor also illuminates seven subthemes in the American story that normally get insufficient attention in conventional narrative renderings of the period.

First, Taylor reminds us that the Wilmot Proviso of 1846, far from being a moral cudgel to keep slavery out of unsettled lands, was largely an implement of white supremacy, designed to keep the territories free of Blacks, widely regarded at the time as a lower strain of human existence. Second, he tells us that a factor in the opposition to slavery in California was to keep Southerners, who possessed the extra labour provided by their human chattel, from monopolizing the search for gold. Third, he illuminates the logical inconsistency between Southern reverence for states’ rights and the region’s dependence on the federal Fugitive Slave Law to ensure that enslaved people who made it to freedom in the North would be returned to their owners. Fourth, he explains that worries about American efforts to annex Canada were especially acute among formerly enslaved people, who had found safety at the border. Fifth, he points to Mexico as another destination for fleeing Blacks. Sixth, he argues that the French emperor Napoleon III, whose invasion of Mexico made him a factor in continental politics, was tempted to enter into an alliance with the Confederacy. And, seventh, he writes that the antebellum United States toyed with annexing Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), a project that was revived during Reconstruction and ultimately rejected by white politicians because of race.

The Canadian angle in this book is especially intriguing, focusing as it does — and here is part of the justification of the broader continental panorama — on a time when both the United States and Canada were facing internal challenges. Led by John A. Macdonald and Abraham Lincoln — both lawyers who were generally self-educated, skeptical of conventional religion, shaped more by ambitious mothers than by feckless fathers, and accomplished in the oratory of the time — the two countries experienced serious strains. In Canada, there was an analogue to American disunion, though far less violent and far less disruptive: the threat propelled by Reform Party efforts to secure increased political representation at the expense of francophone Canada. Macdonald needed francophone support for his governing coalition, but the Reformer McDougall worried that anglophones would “look to Washington” and perhaps facilitate annexation. “Canadian leaders,” Taylor writes, “had to save their own faltering union.”

Across five Aprils, Canada watched the American Civil War with wary eyes. “By building a confederation,” Taylor writes, “Canadian leaders sought to keep the whole bloody mess south of their border with the United States. Farther south, the French imposed a foreign monarch on Mexico. In that foreign interference, Unionists saw their future if they failed to destroy the Confederacy.”

Another striking parallel between then and now is found in the debates over Canadian military spending. Great Britain wanted Canada to pay for its own defence. (A similar impulse at Westminster had been one of the triggers for the American Revolution about a century earlier.) “Despite their British patriotism, most Canadians balked at the high cost of defending themselves against the mighty Americans,” Taylor writes. “Britons should protect them, Canadians reasoned, because the imperial tie alone made them a target for invasion when Anglo-American relations soured.” Eventually, Macdonald countenanced a minute increase in spending — much the way Justin Trudeau has promised to do after repeated complaints from NATO allies and American presidents that Ottawa has failed to uphold its own commitments.

The conclusion of the Civil War brought worries north of the border. The British North America Act of 1867 created the Dominion of Canada, but concerns of invasion persisted, even though, as Taylor argues, “Americans were too busy reconstructing the South to interfere with Canadian confederation.”

In going their separate ways, Canada and the United States had work to do. The United States had a difficult assignment, which Lincoln summarized at the end of his Second Inaugural Address, in March 1865, perhaps the greatest speech in the country’s history. “With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in,” the sixteenth president said, “to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan — to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” Canada, too, had a difficult task ahead: to show charity for minority language groups, to reckon with First Nations, to balance its desire for British ties with its destiny of increased independence, and to find its own way in the world.

“During the late 1860s and early 1870s, Canada, Mexico, and the United States had transformations that strengthened their federal governments,” Taylor writes. “All three national transformations nearly failed.” The Union prevailed only because of late military victories. The Mexican Republic’s survival was ensured in large part by the collapse of the Southern Confederacy, which led to the withdrawal of Napoleon’s brigades. In a memorable turn of phrase, Taylor argues that Canadian Confederation “was a Humpty Dumpty that kept falling — but had to be put back together again because the Union triumph made it impossible for small and separate British colonies to survive in North America.”

It turns out that the American Civil War was a foundation stone of an entire continent. That was not anyone’s war aim, nor anyone’s expectation. But it cannot be denied today. As Taylor makes clear, Canada, Mexico, and the United States are discrete, relatively stable countries in some measure because of nineteenth-century disunion in all three of them.

David Marks Shribman teaches in the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University. He won a Pulitzer Prize for beat reporting in 1995.