When Mario Dumont surprised Quebec by leading the Action démocratique du Québec to forty-one seats and forming the official opposition in Quebec’s Assemblée nationale in March 2007, he already had an impressive track record. During the Charlottetown referendum of 1992, for example, he had challenged Robert Bourassa’s constitutional position, prompting the premier to expel him from the Quebec Liberal Party. Dumont and a breakaway group of young Liberals went on to found the new party in 1994. The following year, he stood with the Parti Québécois premier Jacques Parizeau and the Bloc Québécois leader Lucien Bouchard in the 1995 sovereignty referendum, becoming a dynamic force in Quebec politics.

Éric Montigny, one of the co-authors of À la conquête du pouvoir (In pursuit of power), was an adviser to Dumont and present for many of the discussions and decisions at the heart of the ADQ. His co-author, Pascal Mailhot, worked for Lucien Bouchard; for his successor as premier, Bernard Landry; and eventually for François Legault. They offer readers some tasty insider morsels, including about the shock caused by Parizeau’s bitter words on the night of the second referendum, blaming the defeat on money and the ethnic vote. Bouchard, making his way slowly to his suite (“I am not an Olympic sprinter,” he told Mailhot, referring to continued pain from an amputated leg), missed the speech and was greeted by his chief of staff, who said, “Mr. Bouchard, we have just watched a political suicide, live on television.” Even decades later, the damage resonated: following the Scottish referendum in 2014, a Yes campaign official said, “Contrary to the Quebec independence project, the Scottish project is not ethnic. It is open and inclusive.”

It was clear that the ADQ had momentum while the PQ was fading. When David Levine, a former adviser to Landry and hospital CEO who had been named to the PQ cabinet, ran in a by-election in 2002, it was evident on the ground that his candidacy was doomed and that Marie Grégoire, a key figure in the new party, would win.

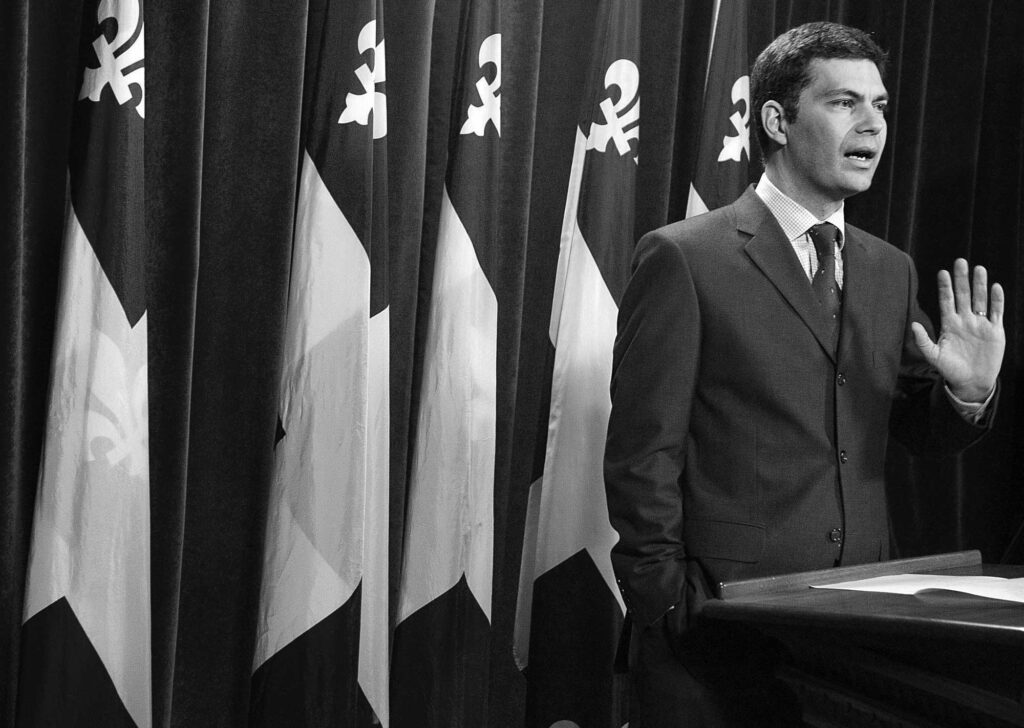

Mario Dumont reacts to the announcement of Jean Charest’s cabinet in April 2007.

Francis Vachon; Alamy

Then came the 2007 election. Jean Charest, in power since 2003, called a winter vote. In the previous months, a controversy had been growing in Quebec over what constituted reasonable accommodation of minorities. First there was reaction to a Supreme Court of Canada decision permitting a twelve-year-old Sikh student to carry a kirpan, a ceremonial dagger, in the classroom. Then a group of Orthodox Jews in Montreal asked a YMCA to frost its windows so that women exercising would not be visible from the street. Dumont seized on this discord, aided by sensational headlines in the Journal de Montréal.

In the campaign, Dumont thrived; the new PQ leader, André Boisclair, sank; and Charest managed to survive. The Liberals were reduced to a minority with forty-eight seats; the ADQ was just seven seats behind, and the PQ had thirty-six seats. This result was traumatic for PQ supporters who, since the 1995 referendum, had consoled themselves with the idea that they were only 50,000 votes away from the promised land — that the No voters were elderly people who would die, making independence inevitable. Instead, brutally, they learned that the flight to a new country was cancelled. The realization led to a collective turning inward by Quebec nationalists.

But, rather than providing a springboard to eventual power, the 2007 election turned out to be the peak for the young conservative nationalist party. While Mailhot and Montigny mention some of the early mistakes, they minimize the naïveté of the band of newcomers elected to the legislature, as well as their leader’s. I remember interviewing Dumont shortly after the election and asking him how he was going to decide where to cut government expenditures in order to achieve the 25 percent savings he had promised if he were elected premier. The new opposition leader said that if the funding for government departments were simply reduced by 25 percent, the rest would happen automatically.

The disappointment that followed, when Charest won a majority in the 2008 election and the ADQ was reduced to seven members, led Dumont to announce his resignation. Since then, he has been a columnist and commentator, adding a note of nationalist fiscal conservatism to the public debate. The party he had founded sank into turmoil with his departure.

In 2009, François Legault resigned his seat in the Assemblée nationale, saying that Quebec was suffering from a “quiet decline”— a play on the phrase “Quiet Revolution” of almost a half-century earlier. But while Legault left the legislature and the PQ, he did not stop thinking about politics, meeting with a wide variety of personalities. At a lunch with Bouchard, he revealed an idea that he had been pondering. Mailhot and Montigny describe the scene this way:

No longer believing in sovereignty in the foreseeable future, the former minister of education declares, a sparkle of determination in his eyes: “Why not create a new party?” A project has been germinating little by little in his mind, he explains: to launch a veritable political start‑up. A party which would attack the problems in education, health, the economy and culture, putting forward the principles of efficiency in the management of the state.

In February 2011, Legault launched the Coalition Avenir Québec alongside Charles Sirois, vowing to root out corruption, reduce government expenditures, abolish school boards, and eliminate unnecessary positions in the public service. Vincent Marissal, then a columnist and now a Québec solidaire member of the legislature, tagged their new political party as indescribable: “Neither on the left or the right, no longer really sovereignists but not exactly federalists.” Or, as someone wrote online, “Like Quebecers! That’s what will make for its success, if you ask me.”

The early going was rocky, though. When Gérard Deltell, who had been demoted as house leader, stepped down to run for Stephen Harper’s Conservatives in 2015, the CAQ lost his seat. Mailhot and Montigny suggest it was reasonable at that point to wonder if the CAQ was about to join the graveyard of ill-fated Quebec political parties, alongside the Action libérale nationale (absorbed by the Union Nationale in the 1930s), the Bloc populaire (which died in the 1940s), the Ralliement créditiste (which expired in the 1970s), the Equality Party (which ceased to exist in 2012), and the Option nationale (which disappeared in 2018). After much discussion and internal debate, Legault adopted a clearly nationalist stance, though with a twist: “A new and modern version of Quebec nationalism within Canada,” as he put it. As the party explained in article 1 of its program, “The Coalition Avenir Québec is a modern nationalist party whose first objective is to ensure the development and the prosperity of the Quebec nation within Canada, while defending with pride its autonomy, its language, its values and its culture.”

The election of 2018 was a triumph for Legault, as he defeated Philippe Couillard’s Liberals and the Parti Québécois, then led by Jean-François Lisée. À la conquête du pouvoir ends shortly after that, with a brief reference to the two most controversial laws introduced by Legault’s government: the laicity legislation and the new version of the Charter of the French Language. The authors describe these as having “great symbolic force, which will mark the accession to power of the third way by touching the very heart of identity.”

Of the first, which bans the wearing of religious symbols by state employees in positions of authority — including police, judges, and educators in the public system — Mailhot and Montigny argue that despite the criticisms of the opposition, the denunciations of some columnists, and the recriminations heard in the rest of Canada, the Quebec population was generally supportive. “Nevertheless, the legislation was the object of court challenges, notably from the National Council of Canadian Muslims and the English Montreal School Board,” they write, snidely echoing what Parizeau called money and the ethnic vote. “But, in the meantime, it is being applied and contributes to defining le vivre-ensemble [how we live together].”

Regarding the language legislation, Mailhot and Montigny offer a brief summary and describe the key role played by Benoît Pelletier, the late Quebec Liberal cabinet minister and constitutional law professor, who endorsed the idea of unilaterally enshrining the status of Quebec and the French language in the Canadian constitution. “If Benoît Pelletier gives his approval, then go!” said Legault. And they did.

À la conquête du pouvoir has the strengths and weaknesses of an insiders’ account. On the one hand, the book includes illuminating details from observers who were on the scene; on the other, its descriptions of the lead actors and their policies are at times uncritical. It gives little hint of Mario Dumont’s amateurism or of François Legault’s ethnocentric nasty streak — and some of the more embarrassing incidents are only briefly referenced. There is also no allusion to or explanation of the fact that Quebec’s current government has only two seats on the island of Montreal — fewer than Maurice Duplessis’s Union Nationale.

Yet testimony from insiders can be just as revealing for what is left out as for what is included. There will come a time for a fuller evaluation of the Coalition Avenir Québec in power.

Graham Fraser is the author of Sorry, I Don’t Speak French and other books.