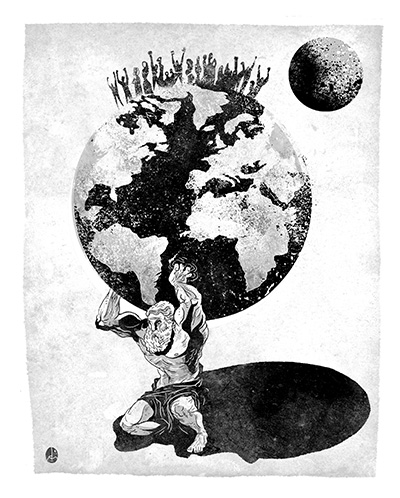

Capitalism, not communism, has delivered Karl Marx’s predicted world revolution. No other system generates such enormous material progress through such enormous upheaval. The same forces that produce ever-increasing productivity and wealth—innovation, competition, the destruction of the old to make way for the new—necessarily also produce incessant change, perpetual turmoil, the permanent disruption of economic and social life. Joseph Schumpeter called it creative destruction. With the collapse of communism and state planning late last century, capitalism entered a new and more radical phase. Today’s turbulent world economy—with its spectacular growth, massive dislocations and seismic power shifts—is the result of creative destruction on a global scale.

As with most historical turning points, this change has taken place first and foremost in the realm of ideas. The same free market policies that produced the “Great Transformation” in 19th-century Europe and America have now been adopted throughout the world. China’s conversion to Deng Xiaoping’s “open door” policy in 1978, the Soviet Union’s abandonment of state planning for perestroika after 1986, India’s switch from inward-looking economic nationalism to outward-looking liberalization in 1991, Brazil’s implementation of the Real Plan and other pro-market reforms after 1994—these economic events, little noted at the time, now look more historically significant than the fall of the Berlin Wall. With the industrialized West’s more modest privatization and deregulation revolution under Thatcher and Reagan in the 1980s, the ideological shift was complete. There are still isolated pockets of state socialism and economic nationalism: North Korea and Cuba are holding out; Iran and Venezuela remain agnostic. But for the first time in history, the free market system is truly global.

Capitalism on steroids

One result is the mass industrialization of the developing world—two and a half centuries after the industrial revolution first swept through England—but at a speed and on a scale that easily dwarf the earlier transformation of Europe and North America. Throughout the 19th century and most of the 20th, the West raced ahead of the impoverished rest—a process historian Kenneth Pomeranz has labelled the “great divergence.” Now we are experiencing a “great convergence,” as the four fifths of world that lives in developing economies rapidly “catch up.” China, with its 1.3 billion people, has grown at around 10 percent a year for three decades—without interruption—passing Japan as the world’s second biggest economy last year and poised to overtake the United States sometime in the next decade. This alone represents the most significant economic miracle in history. The vast Indian subcontinent is travelling the same path, projected to grow at more than 9 percent annually for the next ten years. And Asia’s “growth miracle” is being copied throughout much of South America and Africa. What keeps policy makers in Beijing, New Delhi or Brasilia awake at night is not growing too slowly, but growing too quickly.

This convergence is not new. The United States and Germany caught up to—then passed—Britain over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Japan—followed by Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore and other East Asian “tigers”—blazed a trail for developing countries in the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s. What is unprecedented is the scale and speed of the current transformation. The incorporation of China and India alone into the global economy has quadrupled world productive capacity within a generation—from roughly 800 million workers to over three billion. Since 1980, China’s per capita income has grown an astonishing twelvefold, and India’s has more than tripled. But China’s levels are still only a tenth of U.S. levels (roughly where America was at the end of the 19th century)—and India’s are just one quarter of China’s—illustrating the enormous potential for further catch-up. The developing world’s mass migration from the countryside to the cities is a big part of the story, both reflecting and driving (through economies of scale) further industrialization. In 1950, just 16 percent of Asians lived in cities; today 42 percent do, and this share is projected to reach 54 percent by 2030—a huge increase, but still short of the 80 percent urbanization in the West. Demographics also explain the catch-up story. India’s median age is a youthful 25 and the Philippines’ an even younger 22, compared to 37 in the United States and 44 in Germany. Meanwhile, 98 percent of global population growth—from seven billion now to an estimated 8.3 billion in 2030—will come from emerging economies, further fuelling their industrial expansion. The developing world’s great leap forward is just beginning.

Another result of the capitalist revolution is the rise of a global single market—creating vastly more scope for gains from specialization and economies of scale. The world economy is more open than ever before, partly because of liberalization, but mainly because of new transport and communications technologies. It now costs less to move a container from London to Shanghai—halfway around the world—than from London to Birmingham—just 160 kilometres down the road. The cost of overseas telecommunications is approaching zero, fuelling an explosion of services trade—call centres, computer programming, medical diagnostics. China could not have become the new “workshop of the world” without the trans-Pacific “conveyer belt” provided by advances in containerization. India could not aspire to be the world’s services centre without the hundreds of thousands of kilometres of fibre optic cable laid during the dot-com boom. No sector has been transformed more dramatically than finance. Thanks to modern telecommunications—and a wave of deregulation in the 1990s—the biggest banks now operate globally, as do hedge funds and private equity funds, trading billions of dollars seamlessly among London, New York, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

John Fraser

It now costs less to move a container from London to Shanghai—halfway around the world—than from London to Birmingham—just 160 kilometres down the road.

The trade landscape is being overturned in the process. Expanding trade has been a powerful driver of global growth—providing developing countries with vast markets for their exports, and almost unlimited access to the world’s natural and financial resources—which in turn is driving more trade growth. Britain was the world’s leading exporter in the 19th century; the United States in the 20th; but now China is on top, and is set to remain there for the foreseeable future. The transatlantic trade corridor is being rivalled and surpassed by new trade corridors that link Asia to Europe, Asia to North America, Europe to Latin America, or Africa to Asia. Rotterdam, for decades the world’s busiest port, has been pushed into third place by Shanghai and Singapore since 2004—and Tianjin is catching up fast.

It is not just trade patterns that are changing, but trade’s composition as well. Global production now takes place along complex supply chains—effectively world factories—that locate various stages of the manufacturing process in the most cost-efficient locations around the world. It is not competition between China and the United States that is relevant today, but the competition between Apple’s and Samsung’s value chains. The label on the back of an iPhone—produced by 30 different companies operating across three continents—should read “Made in the World” not “Made in China.” When more than half of trade now takes place within globe-spanning multinational corporations, economic nationalism starts looking at best passé and at worst self-destructive. Despite much hand-wringing lately over the threat of protectionism, the pace of global integration is increasing, not decreasing. World trade was over 50 percent higher in 2010 than in 2000—despite the Great Recession—and 183 percent higher than in 1990.

A third effect—and cause—of global capitalism is the advance and unprecedented diffusion of technology, building on a trend that began with the industrial revolution. The invention of the steam engine, gas lighting and textile machinery at the end of the 18th century triggered a period of extraordinary progress, first in Britain and then across continental Europe. Between 1820 and 1870, average global growth doubled to 1.7 percent from less than 1 percent over the previous 500 years. From 1870 until the outbreak of the First World War, world growth accelerated again to 2.7 percent as technological progress intensified—steamships, railways, the telegraph—and helped open up the Americas. The period after 1945 witnessed another burst of accelerating global growth to more than 3.5 percent, spurred by even newer technologies—cars, jet planes, plastics and telecommunications—that quickly spread to—and linked up—Japan and other fast-industrializing Asian economies.

The global diffusion of new technologies—through the internet, education or multinationals—is driving up the pace of growth again. The World Wide Web did not exist two decades ago; now 2.3 billion people—a third of humanity—use the internet every day. There are 3.5 million students studying abroad (440,000 from China alone)—double the number in 2000—absorbing the latest innovations from Caltech, Stanford, MIT and Cambridge. Of the 8,000 science PhDs who graduated from U.S. universities last year, two thirds were not Americans. No conduit for technology transfer is more important than footloose multinationals. The main goal of China’s open-door policy was not to generate jobs and exports, so much as to use its vast market and low-cost labour to attract the advanced world’s leading multinationals—IBM, Boeing, Siemens, Toyota—and their valuable technologies. That China is now a major producer not just of toys and textiles, but of electronics and computers is a testament to the policy’s extraordinary success.

Just as advances in—and the mass adoption of—technology are driving up the pace of economic integration and growth, so too are integration and growth-generating resources for more research and development and more investment in the communications infrastructure that “hardwires” globalization. Most leading-edge technology is still generated by the already-advanced West. The United States, Germany, Britain and Canada enjoy a huge lead in high-value added exports—such as financial services, capital goods, pharmaceuticals, software, film and television—mainly because knowledge-intensive industries benefit less from low-cost labour and economies of scale. But as emerging economies become more educated and connected, they are becoming innovators and technology leaders too—adding to the positive feedback loop that is driving world progress. Last year, China and India graduated half a million engineers, computer scientists and information technologists each populating the likes of Lenovo, Huawei Technologies, BYD and Infosys.

The result: a world economy that is transforming, realigning and expanding on an unprecedented scale. In 2000 global output amounted to $32 trillion. Even after the financial crisis and global recession, it is now double that size (a fact usually overlooked in decline-obsessed America and Europe). And over the next two decades it is projected to expand tenfold, reaching a staggering $308 trillion. Most of the growth will come from developing countries. But just as America’s industrialization triggered a global economic boom in the second half of the 19th century, and Japan’s rise helped drive even greater growth after 1945, the rapid industrialization of three billion–plus people in the East and South will inevitably benefit the West. The Chinese industrial machine’s voracious appetite for coal, iron, nickel and other raw materials has already driven world commodity prices sky high, fuelling Canadian exports. German advanced machinery exports have also soared, as have Swedish exports of telecommunications infrastructure, Swiss exports of financial services and French exports of branded luxury goods. India’s information-technology giants Infosys and Wipro are increasingly “in-sourcing” advanced services from America, Europe and Asia, not just providing a magnet for “out-sourcing.” Then there is the benefit to western consumers from inexpensive imports—fashion, furniture, flat-screen TVs—and even less expensive capital. The biggest gains, contrary to popular opinion, come from sharing our technology. Knowledge is increased—not lost—when it flows to emerging economies, expanding the global pool of scientists, engineers and innovators who will drive future advances. The media presents economic and technological progress as a race between East and West, a zero-sum game where one side’s gain is the other’s loss, but it is just the opposite. As emerging economies grow in size, technological sophistication and wealth, advanced economies can only grow wealthier, too.

Seeds of Destruction?

But with these immense new productive forces necessarily come equally immense shocks to the existing social and political order, even bigger cycles of creation and destruction, boom and bust.

The disruption is being felt most directly at the level of workers and industries—as changes in the “means of production” have an impact on the “relations of production.” That open trade, innovation and the rise of emerging economies have made the world better off as a whole does not mean that they have made every country—or every group within countries—better off. Capitalism necessarily creates winners and losers, but now on a global scale. The rapid entry of highly competitive, export-oriented giants into the global economy—fuelled by huge investment inflows, new productivity-enhancing technologies and the wholesale transfer of manufacturing capacity—has created a massive global supply shock analogous to the land supply shock that accompanied the New World’s entry into the global economy in the late 1800s. The impact has been a dramatic shift in income from labour to capital across the globe—as the millions of low-skilled workers entering the world’s factories and industries drive down the price of labour-intensive products (such as textiles and toys) and drive up the price of scarce capital-intensive products, both human and physical (such as precision machinery and financial services).

Even as inequality among countries is shrinking, inequality within countries is growing. Hardest hit are other developing countries—Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brazil—exporting the same commoditized manufactures to saturated markets. Even China is feeling the supply squeeze. Its “success” in flooding the world with low-cost manufactures has driven down its own terms of trade by more than a quarter since 1980. The global supply shock is straining advanced economies too, as low-skilled workers increasingly “lose” from globalization even as high-skilled workers (and investors) increasingly “win.” Corporate executives, earning whatever the market will bear, are “rewarded” with vast multiples of their employees’ wages. Financial speculators amass fortunes, not over a lifetime, but in a single year. Consumer borrowing, debt-fuelled rises in home values and growing trade deficits helped America mask this widening wealth gap for decades. But the housing bubble collapse has ended the mirage. Now rising unemployment and falling low-skilled wages are straining America’s social and political fabric. Recent protests have fixated on the extreme wealth of the “1 percent” accumulated at the expense of the “99 percent.” But while bank bailouts and bonuses, tax loopholes and collusive governments are partly to blame, so too are the deeper economic and technological forces that are increasingly dividing societies along class lines—leaving us conflicted about the problem. We vilify the millionaire bankers even as we idolize billionaire Steve Jobs.

One answer is to redesign domestic policies for a globalizing economy: by investing in a skills- and ideas-rich workforce, by helping industries transition to the high-value production that world markets demand and by better sharing the benefits, not just the costs, of globalization. The sterile debate about whether job losses are the result of trade or technology misses the point that society needs creative help in adjusting to a changing world—regardless of the cause. This approach is working elsewhere in the industrialized world. While U.S. multinationals are downsizing or outsourcing, European giants such as Siemens are ramping up their domestic workforce because the skills pool is richer at home: Austrian unemployment is just 4.3 percent, Dutch 4.2 percent, Swiss 2.9 percent. As the architects of America’s New Deal, Britain’s welfare state or Europe’s social democracy understood—but our generation of politicians risk forgetting—people will support economic change only if they can benefit from it.

The disruption is also being felt at the global level. The huge shift in productive power to the emerging world has inevitably set shock waves through the global economy—increasing competitive pressures on advanced economies, destabilizing capital markets and redrawing the map of economic power. One symptom is growing global imbalances, as the export-driven East accumulates ever bigger surpluses and the import-dependent West ever bigger deficits—aided and abetted by integrated capital markets that recycle emerging economies’ savings to advanced-country consumers. China’s policy of systematically undervaluing its currency—to promote exports and keep a vast workforce employed—only exacerbates the problem.

The fundamental weakness today is political. Global capitalism is overturning the existing political order—but we have yet to find a replacement.

To understand how destabilizing and divisive imbalances can be, look no further than the European Union’s protracted battle to reconcile the conflicting interests of its debtor and creditor members. Although global imbalances are the major source of uncertainty and fragility in the financial system today, coordinated efforts to correct them—by increasing Asian imports and shrinking U.S. imports—have scarcely begun. Instead, the U.S. Senate has just passed legislation that would allow America to slap punitive tariffs on China for “unfairly” manipulating its currency. Meanwhile, the United States is effectively devaluing the dollar and flooding the world with liquidity, through quantitative easing (aka printing money). In response to these global shock waves, other countries, such as Japan and Switzerland, are aggressively intervening in money markets to drive down the value of their currencies, while still others, such as Brazil, are threatening unilateral tariff hikes. With good reason, Brazil’s finance minister has warned of looming “currency wars”—a dark echo of the 1930s.

Power is also realigning. Or as Martin Wolf of the Financial Times has put it, the periphery is becoming the core and the core is becoming the periphery. Some now speculate that economic turmoil in the United States and Europe—together with signs that America is prepared to inflate its way to fiscal solvency and competitiveness—will lead to China’s renminbi replacing the dollar as the world’s primary reserve currency in a decade or so. Even without these economic vulnerabilities, the West’s influence is inexorably waning. North America, Europe and Japan constituted almost three quarters of the global economy in 2000 (with just 15 percent of the world’s population), but this share is forecast to shrink to under a third by 2030—a complete reversal of their importance relative to the emerging world. The United States is no longer the global hegemon—a role it has played, at least in the economic sphere, since 1945. Fast-rising powers such as China, India and Brazil are already flexing their muscles to an extent that was unimaginable 20 years ago. This new multipolar world is more “democratic” than the old superpower or hyper-power order. But democracy can also be messy. The old powers are reluctant to share centre stage—obsessed as they are with decline—while the new powers are reluctant to take responsibility for a system in which they now have a major stake. Even within the developing-country camp, old rivalries and new competitive pressures make the so-called BRICS bloc of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa uneasy and restless allies. What can replace Pax Americana?

The danger is that global capitalism is outstripping—even undermining—the international system needed to sustain it. Free markets ultimately rest on political foundations (rules, institutions, social stability), argued Karl Polanyi mid last century; but, paradoxically, left unconstrained free markets can undermine these foundations. The 19th century’s version of globalization catastrophically collapsed in 1914, he suggested, because there was no effective political response to profound economic and technological change. Then, as now, emerging economies threatened incomes and industries in older economies—flooding Europe with cheap agricultural products—while rapid industrialization and technological change divided societies along class lines. Then, as now, the rise of new economic giants, especially Germany, shifted the balance of power and made the old giants uneasy—prompting defensive alliances, an arms race and a scramble for spheres of influence. Nationalism rose; ethnic conflict grew; domestic pressures mounted to block immigration, abandon free trade and turn inward. Many sparks lit the First World War—as any school book can tell us—but the one unifying cause was the disintegration of international trust and cooperation.

In the same way, the fundamental weakness today is political. Global capitalism is overturning the existing political order—but we have yet to find a replacement. Our institutions, systems and mindsets have not caught up with the turbo-charged global economy we have unleashed. Open trade has made us more economically integrated but, in some ways, more politically disintegrated, by exposing differences in regulatory regimes, industrial strategies and political cultures. We have succeeded in creating a global financial system where $3.7 trillion (one twentieth of the value of the entire world economy) criss-crosses the planet every day, but we have largely failed to create the global regulations and policies needed to manage that system—witness countries’ inability to agree on bank capital requirements in the Basel III negotiations, their endless dithering over a eurozone rescue plan or their scramble to impose beggar-my-neighbour devaluations. This is not to mention all the other policy coordination challenges—from taxation, migration, pandemics, the environment—that flow from the rise of a global free market.

Creating the G20 was a step forward—an acknowledgement of today’s multipolar world and a tangible sign that the international system can adapt. But it is not enough. In the same way that the growing reach of markets and technology underlined the logic of new nation-states in the 19th century, and giant regional groupings in the 20th century, today’s global free market demands a level of global rule-making, political coordination and democratic accountability that have yet to be imagined, let alone acted upon. Politicians talk loosely about “global governance”—as if fuzzy words will soften the tough choices—but the real challenge is global government.

Globalization “Is” Us

Will globalized capitalism continue to race ahead? Or will it prove unsustainable, as many have argued since the 2008 financial crash? Marx, the great 19th-century prophet of capitalism’s demise and communism’s triumph, is enjoying a comeback. He was the first to grasp capitalism’s radical instability and inherent contradiction. “Capitalism has created more massive and more colossal productive forces than have all proceeding generations together,” he wrote in 1848, but with it comes the “uninterrupted disturbance of all economic and social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation.” He believed that capitalism was driven to produce ever greater competition, ever smaller profits and ever lower wages, dooming it to self-destruction. In his pessimism about capitalism’s future, Marx was joined by other classical economists—Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo—who could not imagine a world in which economic growth and technological progress continued indefinitely. All were convinced that growth would sooner or later level off, that diminishing returns would set in and that humankind would have to learn to share a static pie. Many of today’s gloom-and-doom prognosticators would agree.

But while Marx was right about capitalism’s inherent tensions, he was fundamentally wrong about one thing: what drives capitalism forward is a race to the top, not a race to the bottom. New products and industries destroy old ones because they offer lower prices, better performance, improved features or eye-catching design—whatever the market demands. New technologies drive out existing ones because they offer better, faster or cheaper ways of producing things—and the resources saved are then put to more productive use elsewhere. In 1900, more than 40 percent of Americans worked in farming; today just 2 percent do—and, thanks to advances in agricultural productivity, we have more food and more choice. Only five of America’s top 100 companies were around a century ago; the list is instead dominated by arrivistes like Google, which is barely 15 years old. This incessant cycle of creation and destruction does not result in our growing immiseration, but in our growing prosperity—Marx’s downtrodden proletariat has become our home-owning, car-driving, cell phone–addicted middle class.

Today’s global free market is producing even faster and more massive cycles of economic death and rebirth—new products, new industries, even whole new economies that only drive progress by destroying the old order of things. And, hard as it is to believe, the world is better off as a result. Never before have so many people—or so large a portion of the world’s population—enjoyed such massive increases in their living standards. Protestors in New York, Tokyo or Sydney want to blame powerful corporations and greedy bankers for masterminding this revolution. But it is mainly us, you and me, millions of consumers—and our insatiable appetite for new gadgets, nicer homes, higher education, healthier lives, more and better “things”—driving the juggernaut perpetually forward. We are the revolution’s foot soldiers. Global capitalism is not something that has been imposed on us—robbing us of our freedom—but a system we willingly choose in the ordinary economic decisions we make every day. Now we need to take political decisions about how to harness and make fairer the colossal economic forces we have unleashed—if capitalism is to be saved from itself.

John Hancock works at the World Trade Organization, where he has served as policy advisor to the director general, head of investment issues and representative to the International Monetary Fund and World Bank. The opinions expressed are his own, not those of the WTO or its members.