They were the two words that came to signify much of the decade—and the debate about the decade—that followed.

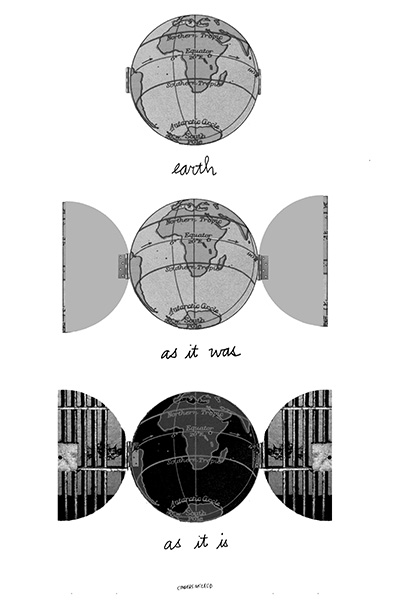

The “dark side” was where former U.S. vice-president Dick Cheney famously described we were headed after the September 11, 2001, attacks jolted the world. “We also have to work, though, sort of the dark side, if you will,” Cheney mused to host Tim Russert on NBC’s Meet the Press. “We’ve got to spend time in the shadows in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies, if we’re going to be successful. That’s the world these folks operate in, and so it’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective.”

The interview came five days after the attacks, as the gruesome wreckage of New York’s World Trade Center smouldered and Pentagon officials mapped out the military plan for Afghanistan while still mourning their colleagues.

Terrorism by definition is a tactic to instil fear in order to bring about political change. As a journalist who covered 9/11 from New York, I do remember that fear. It was in the faces of the relatives, the politicians, the rescue workers and the Pakistani waiter I interviewed in a midtown Afghan kebab house a couple of days after the attacks. He had lost friends in the World Trade Center too, but he knew he was not seen as a victim. He knew he was part of the “other” and he braced for the fallout.

John Fraser

Those who called for restraint in the ways we hit back at al Qaeda both domestically and internationally were branded traitors. Colour-coded warnings told us to be in a hyper-state of alert if we were not already and then came the anthrax scare and we were afraid to breathe or open the mail.

In the United States, the Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act, more commonly known as the Patriot Act, passed with little debate—its name alone a warning to those who dared oppose its new measures.

As Cheney forecast, new counterterrorism policies developed quietly at first, in the shadows, without much discussion. Enhanced interrogation techniques, Guantanamo, warrantless wiretaps, CIA so-called black sites, renditions: it is now a well-known laundry list of tactics and security measures that, once revealed and now with the value of hindsight, continue to be hotly debated.

For those who supported the security-at-all-costs approach, these were vital counterterrorism tools required to combat an enemy like al Qaeda that did not play by any rules. For those who condemn Cheney’s “dark side,” it was a slippery slope that, rather than combating an enemy, offered a recruiting boon for terrorism’s next generation.

But were these measures legal? From where did these policies stem? And have they worked? Ten years on and these questions are still being asked and will continue to be debated for a long time to come.

Into this morass wades University of Toronto law professor Kent Roach with his recent book, The 9/11 Effect: Comparative Counter-Terrorism. “The United States … famously explored the ‘dark side’ of secret executive counter-terrorism measures in the immediate aftermath of 9/11,” he writes. “Unlike in other democracies, many of these American responses were not initially authorized in legislation and they were mainly directed to external threats.”

This is a brave subject to tackle given the fact that it has been such well-covered terrain over the past decade. Luckily Roach’s approach and insight break new ground. Attempting to write what David Garland dubbed the “history of the present,” Roach takes his lawyer’s scalpel to carve away at the U.S. law. He is succinct in his condemnation of what he calls “aggressive assertion of executive power” and “dubious claims of legality” to justify these actions (think waterboarding), but he notes, as few others have, that the U.S. legislative response was in fact “mild compared to the responses of other democracies.”

And this is where Roach’s research sheds new light and corrects commonly held misconceptions. The Patriot Act, while expanding surveillance powers, does not go as far as laws enacted in Australia or Canada, which called for such measures as investigative hearings and preventive arrests. Roach supports this finding with comparative research that goes beyond the “9/11 effect” on U.S. lawmakers, examining how the United Nations, the United Kingdom, Australia and Canada responded as well. He also conducts smaller studies of Egypt, Singapore, Indonesia, Syria and Israel, in part, he writes, to examine how the law changed in established democracies, countries that have dealt with terrorism and those with questionable human rights records.

In general, his findings are disturbing: “The degree of convergence in counter-terrorism law and policy is striking,” he writes, while noting that there have been divergences. Canada and the U.S., for example, have resisted a trend pushed by Britain and the United Nations toward new laws punishing speech that might be associated with terrorism. But on the whole, Roach observes convergence among the countries studied, “often by strengthening the powers of the executive and employing indeterminate administrative or military detention of suspected terrorists without the due process protections generally associated with criminal trials.”

The fear that gripped us after 9/11 should not have hypothetically affected lawmakers, since justice is intended to be blind. Roach shows that is not the case, as each country was influenced by its history, its politics and, in part, its relationship with the United States.

What also makes Roach’s book unique is his focus on the United Nations—which attempted just a few weeks after 9/11 with Resolution 1373 to enact global legislation to criminalize the financing of terrorism, even though, as Roach notes, those provisions already existed and had failed to stop the attack. His criticism is very strong against the UN, and he points out the Security Council’s disregard for human rights in the first three years after 9/11, its often futile emphasis on financing and the General Assembly’s failure to define terrorism. “In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the Security Council and many states prioritized security efforts to prevent terrorism over liberty and respect for human rights,” he writes.

In focusing on Ottawa, Roach writes that Canada was included in the list of countries that panicked after 9/11, but by putting the well-known cases such as Guantanamo detainee Omar Khadr or the so-called Toronto 18, who plotted to bomb downtown and military targets in 2006, in a larger context he concludes that the country had a mixed report card. What makes Canada a unique study is first and foremost its geography, as the real impetus behind Ottawa’s early post-9/11 policy making was concerns with keeping the border open and goods flowing and with quelling U.S. fears of a northern neighbour that was soft on terror. So much so that, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, “Canadian officials cooperated with American officials in secret and problematic ways,” writes Roach.

The most well-known example of this is the case of Maher Arar, who was rendered by the U.S. to Syria after the RCMP passed on erroneous information linking him to al Qaeda. The Ottawa engineer was eventually awarded a government payout of

$10.5 million to compensate for Canada’s role. Roach notes sardonically that “the Canadian government did not spend its limited capital on security issues with the United States by asking for Omar Khadr’s return to Canada.”

Roach’s analysis of Canada also uncovers how immigration laws were used (ineffectively as it turns out) as a counterterrorism tool in the immediate aftermath until authorities relied more on criminal law. Canada leaned on these immigration laws more than either the U.S. or Britain, with its Immigration and Refugee Protection Act allowing for “the removal of noncitizens on the basis of secret evidence not disclosed to the deportee.” And like other countries, Canada has failed to develop review bodies to keep pace with the expansion of the government’s investigative counterterrorism powers.

But it is the exceptionalism of the Americans that interests Roach the most, both for good and ill. He zeroes in on “extra-legalism [that] uses resources within the legal system … to shelter illegal practices from legal challenge. Large parts of American antiterrorism efforts, even under President Obama, fit into an executive- and war-based model, with targeted killings not being subject to judicial review” and simply rubber-stamped by Congress. On the other hand, the fact that we know about so many of Washington’s executive abuses of the last decade “is another sign of American exceptionalism, as manifested by the activity of a free press that is unrestrained by official secrets acts found in most other democracies.”

Neither Canada nor any of the western countries Roach surveys has paid much attention to community- or prison-based rehabilitation programs for those convicted of terrorism offences or seen to be at risk.

“Like other Western democracies, Canada seems at a loss of what to do to rehabilitate terrorists other than to impose long prison terms,” he writes. In this respect, perhaps surprisingly, Singapore stands out as a leader. Having inherited British colonial emergency powers, the country did not have to tweak its laws very much after 9/11 to deal with terrorist threats. But it has concentrated on rehabilitation through “interracial harmony circles,” which are controversial but which result in some engagement with “neighbor terrorists” while these people are still viewed in the western democracies as a “demonized outsider[s].” Roach quotes a recent RAND study that reports on a Singaporean program that has released 40 to 60 Jemaah Islamiya detainees, with only one subsequently rearrested. By contrast, the U.S. government estimated that out of 600 detainees released from Guantanamo with little rehabilitation effort, 25 percent are either known or suspected of being involved once again with terrorist activities.

What Roach does not do throughout the book is delve deeply into individual cases—which is both the book’s strength and weakness. This allows him to keep the focus on the legal analysis and put case law into the greater context of counterterrorism policies, rather than dwell on the personal stories of the suspects or their victims.

This lack of storytelling sometimes makes for tough reading, though, and the book cannot be compared to historical studies such as the surprisingly compelling The 9/11 Commission Report, which chronicled the findings of a bipartisan committee in a non-fiction narrative. Roach is a skilled, crisp writer who avoids legalese, but The 9/11 Effect is geared more toward the legal or academic community than the general public.

Which is a shame, as The 9/11 Effect is essential reading to understand the last ten years of law making and the politics of fear that affected its development.

Michelle Shephard is the national security correspondent for The Toronto Star and author of Decade of Fear: Reporting from Terrorism’s Grey Zone (Douglas and McIntyre, 2011) and Guantanamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr (Wiley, 2008).