It is 1882, and Egerton Ryerson, who shaped Ontario’s system of public education as no other individual before or since, speaks to a patriotic gathering at the Bay of Quinte. They have assembled to commemorate the centennial of the arrival of exiled United Empire Loyalists there. His lengthy address winds its way to the subject of 1812; that was when “the true spirit of the Loyalists of America was never exhibited with greater force and brilliancy.” At that time, “the Spartan bands of Canadian Loyalist volunteers, aided by a few hundred English soldiers and civilized Indians, repelled the Persian thousands of democratic American invaders.” Ryerson draws a line stretching from ancient Greece to 1812, both points on that line glowing with underdog victory and the preservation of superior cultural values, Ours versus Theirs.

That myth of 1812 as a vindication of Canada’s ways, however diluted and remixed for present-day consumers, speaks to us still. It includes a set of qualities that we enjoy possessing, or aspiring to possess: multicultural inclusivity (the battlefield presence of First Nations), militancy in the face of external threat (standing on guard for Thee, We, Me), and the forceful and enduring establishment of national boundaries.

In contrast to earlier commemorations of 1812 and all that, this current bicentennial extravaganza has been on a grand scale, presenting a hodgepodge of re-enactments, children’s opera, ethnic commemoration, fireworks displays and self-hugging speeches ((See Daniel Schwartz’s “War of 1812 Reinterpreted over the Centuries,” CBC News, June 18, 2012, www.cbc.ca/news/politics/story/2012/06/15/f-war-1812-commemorate.html.)). How do we respond to all that, for surely so profuse an outpouring of nostalgia and national pride demands something beyond objective acknowledgement.

We could start by noting a few of the uninvited guests. Like wicked stepmothers, they wait to pounce on the gleeful celebrants. Begin with the First Nations allies, the tribes whom Brock and the British so cleverly used to terrify and overawe the invading Americans. They lost everything: territory, cohesion, recognition. Sacrificed at the peace table like sullen pawns, they found themselves shunted aside at war’s end, devolving from betrayed ally to collateral damage. The newly Canadianized victors that the white settlers began transforming themselves into lost as well. They lost the vision of a democratic social order, with its economic and social dynamism. Upper Canada’s elitist social and governing structure prevailed.

Dmitry Bondarenko

Any attempt to loosen that iron corset around Upper Canada’s spirit became “American,” a mark of sedition and rebellion, a mask for reversing 1812’s affirmation of the God-given soundness of the habits of colonial rule. Methodism, for example, whose populist rituals and message threatened an Anglican establishment, was reviled by such ecclesiastical princelings as John Strachan on the grounds of its American and levelling propensities. Fear and defensiveness, and a social and political order justified on these grounds, marked our social psyche.

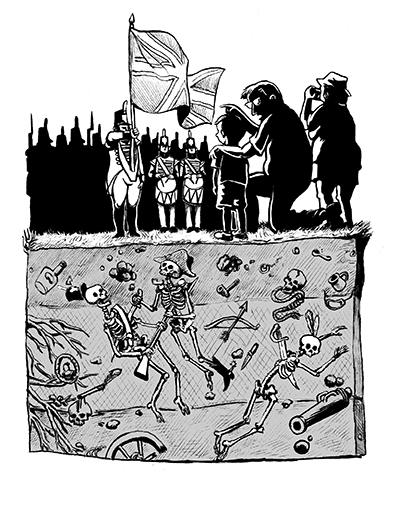

Reading our past through an 1812 lens lumbers Canadians with what the U.S. scholar Franny Nudelman calls a “battlefield nationalism,” a nativity narrative attributing national identity to the atavist rituals of blood sacrifice. Battlefield nationalism keeps adding to its narrative, as when Mackenzie King termed Vimy Ridge (and our imposing monument there) an altar of national sacrifice. Our current rhetorical inflation of our war dead into “the Fallen” represents another addition to the cult. Battlefield nationalism veers off finally into a death cult, a conviction that without the shedding of blood there is no nation building.

We can easily understand why a government intent upon enhancing the image of our armed forces and of the role of force in international affairs just might find commemorating 1812 a safe bet. It is also why a pushback materialized from the descendants of pacifist religious traditions, such as the Mennonites and Quakers who were present around Stouffville at the time of the war ((See Carys Mills’s “Bicentennial Events Decried as ‘Affront’ to Pacifist Roots,” Globe and Mail, May 5, 2012.)). You cannot make that public-memory omelette without breaking a few factual eggs. How else could you highlight the contrast between Good and Evil, Them and Us, that public myth making entails?

When you open your invitation to a party, it helps to know just what it is you are being asked to celebrate. The historians, cultural and political, can help with this search. Some titles produced for this occasion, and even before, demonstrate that professional historians find the significance of events at times cloudy, a bit less definite than the re-enactments, memorials and press releases might opine. Any war ends up having more than one side, more than one outcome, more than one narrative and meaning for those surviving it. What do you do when the very world that you thought that you were fighting to defend has, in fact, vanished? What if history now appears like an abandoned stage set, a cluster of ruins?

For many, 1812 was that kind of fight. A rarefied perspective shows one newly autonomous imperial fragment (the United States) trying to snatch the territory of a colonial dependency of that selfsame empire that it had sundered itself from. Within that 1812 settler set-to, another war took place that shattered any hope of an aboriginal society ever posing a credible threat to settler expansion. To name names: the United States failed to annex the settler societies of the provinces of Upper and Lower Canada that it had invaded, and those societies found a new anti-identity: whatever they were or would become, they would not be American.

James Laxer’s Tecumseh and Brock: The War of 1812 presents a comprehensive account (he includes Andrew Jackson’s war against the Creek tribes of the American South that 1812 gave the U.S. a pretext for waging) of this mixed-up, mixed-result war. Clearly written and presented, Laxer’s account could serve as a definitive, one-volume account of the war for the general reader. D. Peter MacLeod’s (and others’) Four Wars of 1812, the companion volume to a Canadian War Museum exhibit, gives us a similar message through its compact survey of various images and objects from the war accompanied by a brief and cogent commentary. The reader can juxtapose the 2002 special issue U.S. silver dollar profile of Tecumseh (for whom we lack an authoritative image) with the 1814 British Alliance medal bearing an image of King George. The two medallions show so clearly who counted at the time, and how earnest and incomplete any current attempt at rehabilitation seems. Both of these volumes follow in the wake of Alan Taylor’s 2010 instant classic, The Civil War of 1812. Limited in scope to the border conflicts—Detroit, Niagara, southern Quebec—Taylor’s history lives up to what its title promises. There you will find British regulars born in Ireland deserting to the American side and settling there after the war, Upper Canadians and Americans in split families fighting against each other, and settlers beset by warring predators frantically switching sides.

From the point of view of the Reverend John Strachan and the very narrow Upper Canadian elite he taught, networked and spoke for, the war emphasized clear-cut divisions. On the one hand, there were the Loyalist settlers arriving as defeated refugees from the American Revolution; on the other, the “Late Loyalists,” the name given those post-Revolutionary Americans who took up Governor John Graves Simcoe on his calculatedly risky offer of free land in Upper Canada in exchange for an oath of allegiance. One group (you can guess which) unfailingly supported the defence of Upper Canada, the other traitorously welcomed the invaders. Yet, as Taylor and others make clear, “loyalists” and “traitors” came from no single group. As in any invasion of settler territory, the side you supported depended on just who was standing near your barn with a torch in his hand.

When that ruling colonial elite staged a mass hanging atop Burlington Heights in 1814, they drew a line in what they hoped was a rock. The eight selected from among the numerous disaffected—ranging from armed combatants to hopeless men drifting into the roving bands of aggressive neighbours—served as testamentary corpses to the elite’s assumption that treason could be simply and legally defined, and that their institutions had survived the conflict intact and triumphant. You could build a Tory utopia, it seemed, on dead men’s bones. As Dennis Lee put it a while ago: “The dream of Tory origins/Is full of lies and blanks.”

The generalization about 1812 that can stand is that both sides got themselves into a very nasty border war, with the Niagara and Detroit regions invaded and reinvaded by armies and criminal bands looting and burning whatever they took a mind to. The Yanks torched York, and the Brits Washington, everybody torched Niagara, and so it went.

Take one young man’s war experience as it ranged from the ludicrous to the atrocious. John Richardson, who later became Canada’s first-born novelist and then finally died of malnutrition in the New York that he thought would support his work, was doing very mundane work in 1813. He was trying to cut himself out of the tight American boots that he had bought off a looter. He had just found out that those boots once belonged to a Kentucky soldier who had become a martyr in the minds of Richardson’s present captors. Previously, Richardson had seen American scalps dangling from bushes in the camp of his side’s Indian allies. Tight boots and war crimes: the usual soldier’s menu.

So what do we do with our sense of complexity, with the other half of Dennis Lee’s quatrain that I just quoted: “Though what remains when it [the dream of Tory origins] is gone/To prove that we’re not Yanks?” Do we deliver the cynical shrug that Douglas Coupland’s 2008 memorial to 1812 enacts: one life-size toy soldier standing in triumph over another, both in the same frozen pose, both conveying no meaning beyond the ironic. What room is there for personal storytelling amid all those master narratives?

The good news is that Thom Sokoloski and Jenny-Anne McCowan (commissioned by Toronto’s Luminato festival) found that room for trying to understand individuals rather than collectives. In fact, they created 200 such rooms. “The Encampment,” a large-scale installation during the month of June on the grounds of Fort York, consisted of 200 A-frame canvas tents, each containing an artist’s interpretation of “the story of an individual living in the Canadas during the War of 1812.” If grand master-narratives no longer suit our way of thinking, then the fragments of individual history seem to. Rightly or wrongly, we trust that those stories of individuals (“people like us,” we misleadingly tell ourselves) convey some sense of actuality, or as much actuality as we choose to handle.

The bad news is inextricable from the good. Unless we know a very great deal about the war and its sites, most of those names on this installation’s guide will appear unrecognizable to us. (Could you wander through a Venetian museum fruitfully if you lacked all knowledge of who St. Mark was and the role he played in Venice’s sense of self?) If an artist presents you with a symbolic, conceptual assemblage about a figure such as Matthew Elliott, wouldn’t you need to know that he worked for Britain’s Indian department? And wouldn’t you need to know that the Indian department dealt more in scalps than in souvenir t-shirts?

Where we do recognize a name, the artist’s interpretation—a few symbolic objects strung together in a small tent—may strike us as obscure, arbitrary and/or downright silly. Certainly the tent devoted to the soldier/novelist John Richardson had all three strikes against it. (But then my “Yer Out!” was the reaction of a professional who has written about Richardson.) That doesn’t mean that he somehow belongs to me. The installation forced me into realizing that public memory—insofar as it exists—is a compilation of random facts and associations that need not follow a paradigm of my own making.

“The Encampment” necessarily throws the viewer into that quarrel with oneself that Yeats said makes for poetry. The fact is, you cannot help relying on a greater narrative to place an unknown figure. Even if you carry a smartphone with you (as some spectators did) and look up the figure whose tent you are looking at, the information you get there will only make sense as part of some larger story. You will want to go back to those written accounts that I mentioned above—Laxer’s, MacLeod’s or Taylor’s—because they tell it in the linear fashion that will give you the necessary purchase over the conceptual realizations. Even if all you know is some propagandized master-narrative whose origins and aims you distrust and despise, you will inevitably make use of it.

At the same time that you are seeking out a sense of the nature and deeds of an individual swept up in a tsunami of disruption, you are also trying to chart the path of that giant wave. Your response has to navigate the tension between individual and tribal behaviour, between the public and the private. If all you know of William Dummer Powell is what the installation shows you (a bucket of blood), then you need to find out that he did not work in an actual abattoir, but was a prominent figure in the public execution that I mentioned above. And if you already know that, then shouldn’t you also find out something about the reasons for the executions, the ruling elite’s panic that lay behind the so-called “Bloody Assizes”? And then wouldn’t you want to know about the role played by the American looting and burning of York in 1813 that helped bring about that grande peur? And where do you finally stop? Well, of course, you cannot; following that endless spiral of comprehension and puzzlement is called learning history, and it is never easy or complete.

Public memory resembles an archeological site as it actually exists in the muddle that is fact rather than in clarity of theory, where all those disparate layers you look at are neatly discrete. A couple of summers ago, I found myself fulfilling a boyhood dream: I stood at a place that archeologists consider to be the ruins of Troy. There lay a tangled mass of stones and earth whose only meaning for me lay in my own experience of a poem I cannot even read in the language it appeared in so long ago. All the time, I kept glancing at a postcard that I had bought at a shop near the big wooden horse (!) at the entrance. The “artist’s conception” of the site in its heyday owed more to a movie set than to these diggings I beheld. Surely some revelation lay at hand! But then it was time to get back on the bus and visit Gallipoli. What else could I do?

Thus, for me all the energy and dollars poured into the 1812 Bicentennial tell me less about history than about my own mental making of a version of it. Facing up to my own inadequacies, biases and gaps works better for my understanding than flags waving and bands playing. But I want them both, the quiet contemplation and the ruffles and flourishes. Because however inadequate, they are all devices by which we attempt to get some sort of purchase on a past too remote to recall but too important to disregard.

Dennis Duffy has been reviewing books in various Toronto media outlets for more than fifty years. He also delivers occasional art talks at the Toronto Public Library.