For six or seven unprecedented decades, Canada and its allies shared three powerful assumptions: that democracies would multiply, trade would grow, and borders would stay open. NAFTA and an enlarging European Union were poster children for these megatrends. Sadly, in the age of Trump, Brexit, and COVID‑19, all three comforting nostrums — signs of history’s seeming drift toward better times — have hit the buffers. According to Freedom House, an independent watchdog based in Washington, the world has seen fourteen consecutive years of democratic decline since 2006. The Brookings Institution reports that exports as a share of global GDP peaked in 2010. And since 2015, a global migration crisis, a series of travel bans, a smaller EU, and now a pandemic have brought hard borders back with a vengeance, overshadowing the scores of fences, barriers, and walls erected in the decades since 1989.

The many clues point to Canada.

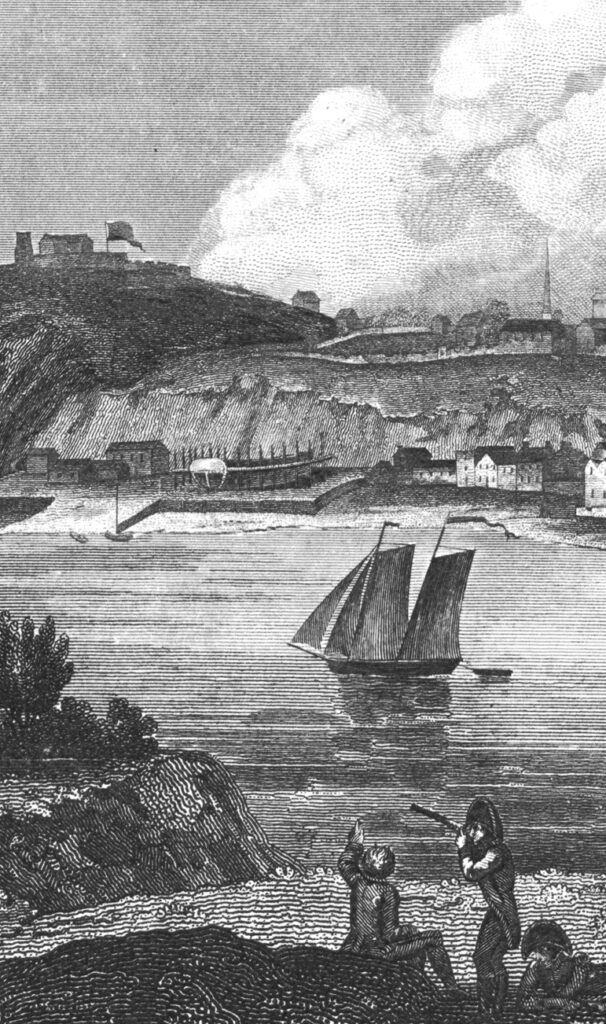

W. M. Craig, View of Quebec, The capital of British America; Library of Congress

With many land crossings closed and democracies tottering, now is the right time to look back on the origins of Canada’s own border with the world’s first full democracy and top trading partner. Well before 1776, democracy, entrepreneurship, and openness were formidable forces in America. Faster than the United Kingdom itself, the thirteen colonies fulfilled Adam Smith’s prophecy about the end of mercantilism. After independence, even as the United States remained blighted by slavery, segregation, and racism, it became a pole of attraction for tens of millions of immigrants — first European, later Asian and Latino — who powered waves of innovation and transformation. Since the Civil War ended in 1865, America has been the engine of globalization, defined by the Peterson Institute as “the growing interdependence of the world’s economies, cultures, and populations, brought about by cross-border trade in goods and services, technology, and flows of investment, people, and information.”

But the U.S. has sometimes taken its foot off the gas and stepped away from global leadership. The first instance was a decade of instability and depression between the two world wars, when Washington was mostly in an isolationist and protectionist mode. The second began with the 2008 global financial crisis, itself triggered by American excess; it tipped our neighbours into disengagement, indebtedness, polarization, and renewed protectionism. This cycle, made more toxic by disinformation and inequality, has engulfed many countries, turning them inward as well. The costs are still being counted.

Once the dust settles from the November presidential election, will the United States reclaim its leadership role for a new era of global problem solving? Although I am among the hopeful, it’s of course too soon to say. But perhaps we can look back to see a little more clearly what lies ahead.

The three-time Pulitzer Prize winner Rick Atkinson knows hard times: as a historian and journalist, he has written about Vietnam, Iraq, and improvised explosive devices. His Liberation Trilogy, about U.S. involvement in the Second World War, is a brilliant literary diorama of campaigns in North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe, as well as a chronicle of the victories that relaunched globalization in 1945. As America struggles to live up to its founding ideals today, Atkinson has returned home to recount its first fight as a country. The British Are Coming covers events from March 1775 to January 1777, two years that are equally crucial to Canada’s emergence as a modern nation.

Atkinson starts his prologue in Portsmouth, England, on June 22, 1773. Arriving from Kew in “a royal chaise pulled by four matched horses,” George III was met by his guard, the Twentieth Regiment (three years later, they would relieve the Citadel of Quebec before surrendering at Saratoga, New York). Rowed out to Spithead in a ten-oared barge, the king reviewed twenty ships of the line “moored in two facing ranks along five miles of roadstead.” These were gunboats of the world’s largest fleet. “Five hundred vessels large and small” bobbed around the monarch, who enjoyed a thirty-one-course banquet that afternoon on board the ninety-gun Barfleur. The naval review lasted four days.

Atkinson’s scenes are almost cinematic, as he unfurls the tapestry of what would prove a brutal war. The underlying message of his prologue is unambiguous: two years before the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the thirty-five-year-old George already feared that his only hope of pacifying mutinous New England — on edge since March 5, 1770, when soldiers of the Twenty-Ninth Regiment, colloquially known as the Vein Openers, fired on a Boston mob — lay in those “wooden walls” floating near Portsmouth. Without compulsion powerfully delivered, he suspected, disobedience would fester and grow. It was a disquieting thought for the peacemaker of 1763, who had at last put Britain in control of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes.

Duty weighed heavily on George. Conciliation had worked at Quebec, but clouds of discord were gathering further south. When Massachusetts, and then the First Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia, rebuffed even watered-down acts of Parliament, the king made his choice. “Blows must decide,” he wrote to Lord North on November 18, 1774.

The king was far from confident of success. On February 11, 1775, he famously joked, “I do not know whether our generals” — meaning Thomas Gage, who had arrived in Boston in May 1774; three major generals sent to stiffen his spine; and forty-five other senior officers — “will frighten the enemy, but I know that they frighten me.” As it was, in 1775, the decision to use force resulted in British defeats around Boston and in North Carolina and New Jersey, as well as victories in Canada, on Long Island, and in Westchester. (The stunning reversals of 1777 and Britain’s final defeat in 1781 will be central to the next two volumes of Atkinson’s trilogy.)

History’s verdict on this uxorious monarch has been damning. Despite a sixty-year reign that coincided with the Industrial Revolution, George III tends to be either lampooned by posterity or portrayed as an outright villain, the dim-witted author of a catastrophic cock‑up. Lin‑Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton presents both versions, with the pre-porphyria king’s tragicomic descant on sending “a fully armed battalion to remind you of my love.”

In this present political moment of eagerly questioned assumptions and rightly disputed narratives, we need to go beyond caricature. Was it inevitable that George III would be drawn into war? Atkinson, whose focus is on military operations from opening salvo to closing surrender, omits the backstory on which any full answer would hinge; his short prologue covers only twenty-two months leading up to Lexington and Concord. Nonetheless, the clues are many, and most of them point to Canada.

Americans generally welcomed Quebec into the fold in 1763, after France formally ceded it. But disenchantment quickly set in because of a perception of unequal treatment. As the historian Alan Taylor has put it, in describing General James Murray, Quebec’s first British governor, “rather than force French Canadians into a British mold, Murray favored adapting the empire to their culture.” Writing in 1766, Viscount Barrington, secretary at war, said “the two great points in respect to Canada” were to “make the Colony affectionate to us and to make the people happy.” The next military governor, Sir Guy Carleton, shared this conciliatory impulse, spending four years in London, from 1770 to 1774, to build support for a plan to institutionalize it. The resulting Quebec Act was redrafted four times in early 1774, just as Parliament was enacting the Boston Port Bill and other “intolerable acts” that so riled colonists to the south.

On June 3, 1774, Parliament heard from Michel Chartier de Lotbinière, a seigneur: though lukewarm toward the bill, he confirmed that restoring French civil law would be popular. Meanwhile, American petitions to Parliament had been refused. One potential bridge-builder, Benjamin Franklin, had been severely dressed down by the Privy Council on January 29; less than two months later, he was sailing home on a ship from Portsmouth.

The Quebec Act promised “the free Exercise of the Religion of the Church of Rome.” In giving royal assent on June 22, George III said “it was founded on the clearest principles of justice and humanity, and would, he doubted not, have the best effect, in quieting the minds and promoting the happiness of his Canadian subjects.” As news of this measure trickled into harbours up and down the Atlantic coast, groans of indignation hardened into pledges to resist. For many in Massachusetts and Connecticut, free institutions were under threat. In the eyes of almost everyone in the thirteen colonies, the king was siding with Catholics over Protestants. Amid the uproar, a committee of correspondence in Massachusetts declared itself a “Solemn League and Covenant”— a formula used by the parliamentary side in England’s first civil war. This drew a rebuke from Gage, which set the stage for military confrontation in April 1775.

The Quebec Act proved a principal factor that nudged Americans from disaffection into open rebellion. By rejoining lands north of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi to Quebec, London was seen to be reviving New France’s reach into the heart of the continent — and blocking westward expansion by English-speaking settlers. Even the Declaration of Independence, adopted one week after the Continental Army had left its last camp in Quebec, at Île aux Noix, included among its list of grievances the king’s “abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.”

Then as now, borders, land, and religion had popular resonance greater than that of taxes, juries, and even habeas corpus. Outrage against the measures to “placate” French Canadians was general: most of America’s founders, including Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, decried the bill. Samuel Langdon, the president of Harvard College, inveighed against “popish schemes of men who would gladly restore the Stuarts and inaugurate a new era of despotism.”

Atkinson’s first chapter opens on March 6, 1775, a moment of ferment, at the Old South Meeting House in Boston, where Joseph Warren delivered a sermon to mark the fifth anniversary of the Boston Massacre. A few months earlier, in September 1774, Warren had proposed the Suffolk Resolves, which denounced the Quebec Act as a threat to “the Protestant religion and to the civil rights and liberties of all America.” In endorsing them, the Continental Congress declared the resolves were intended to prevent Parliament from establishing “tyranny” in Canada, “to the great danger, from so total a dissimilarity of Religion, Law and government, of the neighbouring British colonies.”

In Robert McConnell Hatch’s words, “There was hardly an American colony that was not incensed by the Quebec Act.” Unsurprisingly, the first major military action authorized by the Second Continental Congress, in June 1775, after morale-boosting victories at Lexington and Concord, was the invasion of Canada, now defended by fewer than 700 regulars (since two regiments had been deployed to bolster the British force at Boston).

The American urge to attack Quebec tapped into folk memory. “For nearly a century,” Atkinson writes, “Americans had seen Canada as a blood enemy.” He rightly distinguishes between irrational fear and historical fact — a line the nineteenth-century American historian Francis Parkman did much to blur. In Atkinson’s assessment, the Quebec Act, which came into force on May 1, 1775, “infuriated the Americans and altered the political calculus.” It did so mostly by inflaming popular prejudice: “Catholic Quebec was seen as a citadel of popery and tyranny.” The northern colony was expected to be easy pickings: “Most Canadians were expected to welcome the incursion, a fantasy not unlike that harbored by Britain about the Americans.” As Atkinson adds archly, “This would be the first, but hardly the last, American invasion of another land under the pretext of bettering life for the invaded.”

Before the campaign was even approved, enterprising Americans had taken matters into their own hands. In May 1775, Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga, on the south end of Lake Champlain, with its “noble train of artillery.” They also raided Fort Saint‑Jean on the Richelieu River. Atkinson glides over these events swiftly, despite the forceful nudge they gave to congressional decision-making and the kinetic role the captured guns played in prompting the British to quit Boston.

Arnold’s bold actions had outsize consequences. Together with Allen, he was a chief advocate of the Canadian invasion. When others were captured (Allen), fell ill (Philip Schuyler), or were killed (Richard Montgomery), Arnold kept going, drawing on his merchant shipping experience to stymie Carleton’s advance down Lake Champlain. In 1777, Arnold was again central to British reversals, bluffing Barry St. Leger into retreat in August and fighting John Burgoyne to a standstill in October, all long before his defection in 1780. (A deep irony of the American Revolution — and a key to its complexities — is that Arnold settled in New Brunswick in 1785, and his family was later granted over 13,000 acres in Upper Canada.)

The first year of “the war for America” was actually dominated by a war for Canada, with the Quebec Act a principal casus belli for both. For nearly half of the twenty-three months covered in The British Are Coming, the Continental Army was in Quebec. Yet Atkinson devotes only three of twenty-two chapters to the invasion, leaving out the Battle of the Cedars, in May 1776, so critical to the liberation of Montreal. In the end, more American soldiers were captured at Quebec, the Cedars, and Trois-Rivières than at the Battle of Long Island.

Atkinson mentions the lexicographer Samuel Johnson, but not Sir William Johnson, the architect of British Indian policy, whose nephew Guy Johnson convened over 1,000 Haudenosaunee and other First Nations representatives at Oswego, New York, in July 1775. With Carleton also present, this council was a defining moment of the war: Britain’s Indigenous allies undertook to defend the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes, but not other colonies. To this day, the CanadaU.S. border runs along the St. Lawrence from Lake Ontario to Akwesasne — through Mohawk territory that straddles the international boundary. Even Sir John Johnson, Sir William’s heir, is absent from The British Are Coming, despite his showdown with Philip Schuyler at Johnstown in January 1776 and the precedent he set for other loyalists in May 1776, when he fled to Akwesasne with hundreds of armed supporters, mostly Catholic Highlanders. (For this broader story, Gavin Watt’s Poisoned by Lies and Hypocrisy: America’s First Attempt to Bring Liberty to Canada, 1775–1776, from 2014, is a good source.)

Atkinson is strong on the British withdrawal from Boston; the campaign to reoccupy Long Island, Manhattan, and Westchester; and the first battles in Virginia and North Carolina, including the decisive American win at Moore’s Creek. With his description of Franklin’s diplomacy at Paris, the playwright Pierre Beaumarchais’s covert gun-running, and George Washington’s close-run victories at Trenton and Princeton, the shape of eventual American victory is clear long before John “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne launched his ill-fated Saratoga campaign.

By 1774, America had made up its mind: 3,059 days of seesaw hostilities merely prolonged the agony. Yet the main protagonists, as is so often the case, were prisoners of their own limited perspectives to the bitter end. For the British, victories at Quebec on the last night of 1775 and at Fort Washington, New York, on November 16, 1776, created an illusion of success sufficient to renew the campaign. Gage, Burgoyne, William Howe, and Henry Clinton, the British generals calling most of the shots, left distinctive imprints. But their efforts were doomed. Only Carleton, the defender of Canada and protector of the Loyalists, achieved his main objectives.

Why did George III fail to put down a rebellion when his predecessors had succeeded in Scotland, Ireland, and Acadia? The short answer is because of ignorance, scale, and changing times. The king was a polymath, but what his ministry did not know about America would have filled his 65,000-volume library. The task was far too vast: Scotland’s Jacobite armies in 1715 and 1745–46 had fielded about 35,500 soldiers; in America, an estimated quarter of a million rebels took the field. Moreover, repression was falling out of fashion. As Enlightenment ideals and the romantic movement further entrenched the primacy of the individual, it became less acceptable to compel consent. In effect, Britain lost the information war — the battle for the affections of ordinary people — almost before it began.

A century of benign neglect had produced a muddle in colonial affairs, a habit of autonomous self-government (of which London was unaware) that shakily coexisted with a presumption of parliamentary supremacy (which colonists ignored). For many Americans, the Crown had become an unrepresentative burden. They pointed to the rapacious East India Company and the sugar barons of Jamaica and Barbados, who had more voices in Westminster than the thirteen colonies. If the king had decided against force in late 1774, he would have been hastening the inevitable. American autonomy was irreversible.

The war for America eventually came to comprise 1,300 battles or skirmishes on land and 241 naval engagements. It took 26,000 to 36,000 American lives — one-third each from battle, disease, and imprisonment. This was the largest proportion of the U.S. population to perish in any conflict outside the Civil War. Atkinson does not mention the British toll — over 40,000 dead, with a slightly smaller proportion killed in battle and more by disease. He also downplays another dramatic result of Britain’s defeat and America’s failed northern invasion: the migration of over 100,000 Loyalists to Nova Scotia, Quebec, and other parts of the empire.

In the end, Atkinson’s gifted storytelling is tarnished by millenarian language and incomplete analysis. For Loyalist refugees and their Indigenous allies, the emerging United States was anything but a “majestic construct” where “beyond the battlefield, then and forever, stood a shining city on a hill.” They had been persecuted and jailed. Their property had been confiscated. Exile beckoned. (Those seeking a broader perspective should read Taylor’s American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750–1804, Maya Jasanoff’s Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World, or Michael McDonnell’s Masters of Empire: Great Lakes Indians and the Making of America.)

Among those who experienced the “American War,” as many called it in Quebec, each individual story was different. The vicissitudes of a civil war fought in backcountry farmsteads and remote outposts, as much as on fields of battle, forced many people to be shape-shifters or turncoats. Allies became traitors; ambiguity and self-interest governed all. After Lotbinière’s appearance before the House of Commons in 1774, for example, which helped Carleton win votes for the Quebec Act, he lost his bid to recover two seigneuries on Lake Champlain. So he went on to Paris, where the French foreign minister, Comte de Vergennes, hired him as a confidential agent; by June 1776, he was introducing himself to John Hancock in Massachusetts, contrary to the count’s instructions. But the family’s flirtation with revolution was short-lived. Lotbinière’s son, a British officer captured by American forces in November 1775, went on to become Carleton’s confidential agent. Throughout the invasion, militia officers from seigneurial families played major roles in defending Canada — including François-Marie Picoté de Belestre, Joseph-Dominique-Emmanuel Le Moyne de Longueuil, and Charles de Saint-Ours at Saint‑Jean, as well as the de Lorimier brothers at the Cedars and Louis Liénard de Beaujeu de Villemonde at Quebec.

During the six-month siege of Quebec and its fortress, only seventy British regulars were present in the garrison. Locally recruited militia and Royal Highland Emigrants, veterans of the Quebec campaign who settled in Canada after 1763, played the more decisive role, alongside British sailors and marines. While some habitants rallied to American colours and the Continental Army received supplies from dozens of parishes around Quebec, much to Carleton’s chagrin, the indulgent policy he and Murray had adopted toward clergy, seigneurs, and notables ultimately won the day.

The role that seigneurial families played between 1774 and 1777 has not been fully told. But the picture is clearer thanks to La noblesse canadienne: Regards d’histoire sur deux continents, an excellent survey of the nobility of New France by Yves Drolet and Robert Larin. They examine a core of about two hundred families, with thousands of descendants living today, who were either nobles de fait (meaning they signed themselves as écuyer and were treated as nobility by their peers) or nobles de droit (descended from families whose nobility had been legally recognized by the state under lettres de noblesse or charges anoblissantes after the reforms of Louis XIV and Colbert in 1660).

Most had come to Canada as civil office holders, or as officers in the Régiment de Carignan-Salières or Troupes de la marine. Many had played key roles during the Seven Years War. Theirs was a hybrid social group, with internal cohesion founded on heredity and porous boundaries open to new entrants on the basis of ambition, merit, talent, or wealth. Drolet and Larin describe it as a closed legal order (un ordre légal fermé) alongside an open social group (un groupe social ouvert).

The snobbish Carleton had several nobles de droit on his staff; children of Luc de la Corne and others married senior British officers and officials. But postwar prominence went mainly to nobles de fait, particularly those related to Le Moyne de Longueuil, Picoté de Belestre, and Fleury Deschambault. After the Quebec Act and again following the 1783 peace, many members of this extended family, mostly the cousinage of the Baroness of Longueuil, were rewarded with places on the Council for the Affairs of the Province of Quebec, the upper house. Ironically, the invasion of 1775–76 had made the colony more Catholic, more francophone, more loyal.

Even for the defeated, the commercial cost of the war was short-lived: British exports to the United States, £4.4 million in 1773, rebounded to £3.7 million by 1784. Early globalization resumed, albeit with new obstacles in its path. Ancien régime France, shorn of Canada but proud of its role in splitting America from Britain, soon lurched into revolution and continental war, disrupting trade for a generation. When global exchange began to grow again in the 1820s, there were few comforting nostrums. But for Canada and many other countries, the economic tailwinds were strong. The U.S., even while achieving commercial pre-eminence, remained largely aloof from world affairs through Reconstruction and into the Gilded Age.

Since 1945, America’s role has been altogether different: the relentless impresario behind the Bretton Woods system, the UN, and NATO has led more often by cultural and economic example (Wall Street, Hollywood, Silicon Valley) than by strategy (Vietnam, Iraq, Syria). As at its founding, so at its moments of greatest global influence, the superpower of creativity and imagination has been subject to intense bouts of overreach, self-delusion, and popular prejudice.

America’s founding ideals, which square easily with its Cold War leadership, culminated in enlarged European institutions and dozens of new democracies in every part of the world. Did those same ideals drive corporate America’s love affair with China, consummated by Kissinger and sustained by the two Bushes, Clinton, and Obama, which allowed a one-party dictatorship — one that has refused democracy, freedom, and the rule of law — to become the nation’s principal economic partner?

In resisting British coercion, Americans had just cause. The larger arc of hostility to Quebec — that corrosive cocktail of jealousy, religious chauvinism, and self-interest that brought committees of correspondence to life in 1774 — is much harder to explain. Even now, a quarter of a millennium later, it remains astonishing and instructive that the rebellious colonists’ first military priority after Lexington and Concord was not the liberation of Boston but the attempted subjugation of Canada.

In the final analysis, both George III and the Continental Congress made the same mistake: they tried (and failed) to compel consent by force. The result was two new democracies launched on the North American continent at virtually the same time: one with the ratification of the U.S. Constitution in 1788 and the other with the Canada Act of 1791. It is indeed an old question that arises again today: Does the United States have the reserves of self-awareness necessary to see the bigger picture, to supply the hard explanations that the next phase of globalization will require, and to recover from its latest bouts of self-delusion, polarizing intolerance, and dictator-abetted isolationism? We’ll see.

Chris Alexander served as Canada’s ambassador to Afghanistan from 2003 to 2005.