R. Murray Schafer is many things to many people. To some, he is an educator. To others, he is an environmentalist, sociologist or perhaps even a cultural theorist. Still to others (myself included) he is primarily a composer of music. He could also be called a professor, a poet, a visual artist, an eccentric, an iconoclast and a back-to-the-land hippie.

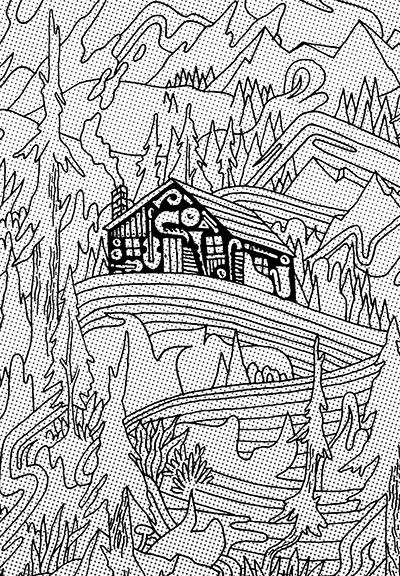

Schafer evidently heeded Benvenuto Cellini’s advice that no one should attempt an autobiography before the age of 40. In fact, the polymath of Indian River, Ontario, doubled down on this proposition, waiting until his 80th year to publish My Life on Earth and Elsewhere. The book has the glow of sincere conviction about it that adumbrates just about everything Schafer says and does. It is a well-written account of a remarkable life remarkably lived. (It is also well illustrated, with photographs and Schafer’s own drawings.)

Beginning with his earliest memories of childhood in Toronto in the 1930s, Schafer recounts an artistic development that might have been conventional, but certainly was not. He was not born to unconventionality, and he did not have it thrust upon him, either. Rather, he achieved it—by getting himself thrown out of the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Music and travelling to Europe to become a wandering scholar. Writing music, at this time of his life, seems to have been almost a byproduct of his quest for humanistic knowledge of all kinds: he visited the theatres of ancient Greece, read Dante in Italian and hobnobbed with Ezra Pound.

Soon, however, music and sound emerged as dominant forces in his self-invented life. With the national broadcast of his bilingual opera Loving (Toi) in 1966 (on both English and French CBC television), he became a prominent figure in contemporary classical music. At about the same time, he took a teaching job at newly established Simon Fraser University, near Vancouver, and began his groundbreaking work in music education and also his research into “soundscape” ecology.

Jake Pauls

In true Schaferian form, he resigned from SFU several years later, when the institution grew too conventional for his taste. It was then that he created the life that he has lived for most of the last four decades: as a dweller in the hinterland, where rural Ontario meets the Great Northern Forest. When he was not tending to his vegetable garden, he was composing or writing books. And when he was not doing any of those things, he was travelling around the world to conferences, to guest-teaching gigs—and to occasional productions of his elaborate “Patria” music-theatre cycle. To this day, this is pretty much how he lives.

Who will read this book? Because of Schafer’s wide-ranging activities, his fan base is diffuse yet devoted—and an international network of “Schafer groupies,” as they might be called, has developed over the years. These people will love My Life on Earth and Elsewhere, for in it they will find a treasure-trove of critical observations, barbed comments and other Schaferisms: “As more and more people crowd into the cities, we are losing contact with the earth, with birds and animals, with sunsets and starry skies.” Or “perhaps, one day, North America will rediscover that music can be made with the simplest materials and a little imagination.” And “Canada may be one of the most desired destinations in the world, but who are we and why are we together? It is an embarrassing question.”

What emerges from the narrative is a rebellious artist who is both conjoined to and at odds with the infrastructures of Canadian art. With obvious pride, he recounts an act of subversion, in the 1970s, when he received a commission for a new orchestral work from the Toronto Symphony Orchestra—on condition that the piece should be no more than ten minutes long. Schafer made this restriction the work’s title—“No Longer Than Ten (10) Minutes”—and he naughtily instructed the orchestra to repeat the final passage whenever the audience (believing the piece to be over) began to applaud. Thus, the short piece could theoretically continue indefinitely. At the premiere, confusion and pandemonium reigned in the hall.

As well, a vein of strident Canadian nationalism (of a sort that has grown rather quaint these days) runs through the book, with Schafer denouncing foreign domination of Canadian culture—especially foreign-born orchestral conductors. In the 1990s, he briefly boycotted the TSO, refusing to allow it to perform his Flute Concerto because the orchestra’s Finnish conductor did not program enough Canadian music.

What else do we learn about Schafer? He plays up his libertarian streak. When he received a copy of the long-form census questionnaire, which asked him such questions as “how much do you spend on electricity?” and “how old is your furnace?,” he refused to complete it. Instead he wrote to Statistics Canada, protesting the “decimalization of humanity.” And he does not shy away from his relationships with women—portraying himself as a man with a healthy appetite but also a sincere heart.

Finally, a sense of bitterness darkens some pages. Schafer is not coy about his desire for recognition—he is more honest than some composers who outwardly disdain fame while inwardly lusting after it—and he makes it clear that he has not really found what he is looking for. However, his quest for fame has played out in strange and ironic ways.

He is one of only a few Canadian composers of classical music whose reputation has spread beyond the borders of Canada. His music is performed in Europe, and he is widely known in Latin America for his educational work. But in Canada, his compositions are infrequently performed—especially the “Patria” cycle. As many of these pieces must be performed outdoors, in remote site-specific locations, few people have actually seen them. As a result, they are both his best-known and his least-known works.

This point leads nicely back to the rhetorical question posed earlier: who will read this book? It would be a fine thing if it found a readership beyond those who already know and admire Schafer’s oeuvre. If this is Schafer’s wish—and it probably is—then it is probably helpful that this life-and-works autobiography is more life than works. (Those looking for an in-depth discussion of his music will find his 2002 book, Patria: The Complete Cycle, helpful. And those interested in his educational theories should look to his The Thinking Ear and A Sound Education.) Nobody needs a PhD in musicology, pedagogy or anything else to read My Life on Earth and Elsewhere.

If Schafer makes no effort to disguise his personal disappointments or his dissatisfaction with Canadian culture, neither does he hide his farmer’s optimism for better years to come. “Beneath it all,” he writes, referring to his motivation for creating deliberately difficult-to-stage pieces, “is a secret feeling that what has been accomplished in works like The Enchanted Forest and The Spirit Garden will one day be reevaluated and pronounced good while the rest of what presently attracts public attention will slip into oblivion.”

If this book helps Schafer to find the broader recognition he deserves, then it will be a very useful book, indeed.

Colin Eatock is a Toronto-based writer, critic and composer. Last year his book Remembering Glenn Gould was published by Penumbra Press, and his compact disc Colin Eatock: Chamber Music was released on the Centrediscs label.