So. It is 1868. In Russia Maxim Gorky is born, in Canada Thomas D’Arcy McGee gets assassinated, and in England astronomer Norman Lockyer discovers helium. In the Wyoming Territory of the United States, meanwhile, the Treaty of Fort Laramie is signed, setting aside for the sole use of the Lakota tribe forever the Black Hills mountain range and all of northeastern Wyoming.

Before you could say “Fort Laramie Treaty,” White miners swarmed into the Black Hills and began digging mines, sluicing rivers, blasting away the sides of mountains with hydraulic cannons, and clear-cutting the forests in the Hills for the timber. The army was supposed to keep the Whites out of the Hills. But they didn’t. A great many histories will tell you that the military was powerless to stop the flood of Whites who came to the Hills for the gold, but the truth of the matter is that the army didn’t really try.

Fortunately, we are not dealing with a great many histories here. In The Inconvenient Indian, blessed/burdened with the subtitle A Curious Account of Native People in North America, noted novelist and broadcaster Thomas King retells the history of this continent from a First Nations perspective, and like Coyote in his well-received novels, he is not going to stop until we well and truly get the point. Which in this case is that the influx of white settlers did not well please the Lakota, who appealed to Ulysses S. Grant to honour the treaty terms. President Grant responded instead with the offer of a $25,000 land grant and an all-expenses-paid trip to a new homeland in the Indian Territory. The Lakota refused then, refused again in 1980 when the U.S. government, following the Supreme Court ruling United States versus Sioux Nation of Indians, upped the offer to $106 million, and they are refusing still. Their point: this is stolen land to which its owners have never ceded rights—which is all very high-minded, except that the sanctity of the traditional Black Hills territory was irredeemably altered anyway back in the 1920s and ’30s when sculptor Gutzon Borglum dynamited the sacred Black Hills mountain, “Six Grandfathers,” to create Mount Rushmore.

As broken promises go, this one is striking—explosive, even—but of course it is not the only one King has at his disposal in this overview of Native/non-Native dealings. The Oka crisis of 1990 was a fight over the desecration of Indian burial land. The Hopi have battled mining companies for the sanctity of their traditional lands. A few kilometres from where I write, the Musqueam only just won the right to protect ancestral remains and a village midden from condo development.

Ethan Rilly

King’s book, which wanders freely and breezily through the 19th and 20th centuries, aims to document the full breadth of accommodation and disappointment and betrayal encountered in Native life. He talks about the depiction of Indians in art (including, of course, western movies, a preoccupation of his), the fixing of Natives in the amber of pop culture, and the casual, enduring racism of law makers, politicians and neighbours. He dekes energetically, drawing deft connections between seemingly disparate experiences, but never does he stray far from his central topic: “Land has always been a defining element of Aboriginal culture. Land contains the languages, the stories, and the histories of a people. It provides water, air, shelter, and food. Land participates in the ceremonies and the songs. And land is home. Not in an abstract way.”

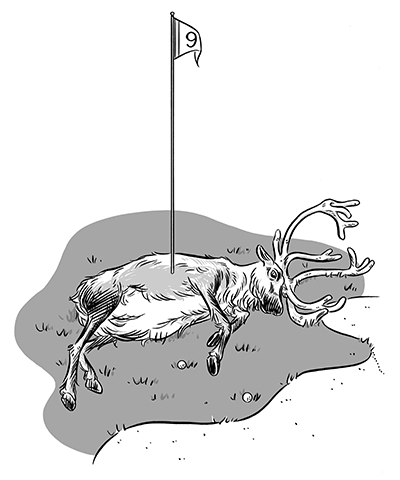

The case for the prosecution returns again and again to land. To the theft of the Ipperwash lands from the Stoney Point Ojibway; to the 3,300 acres of Nisqually land in Washington state annexed to the Fort Lewis artillery range and to the Nisqually’s river lands routinely barred from their fishing access; to the entire Seneca reservation in Pennsylvania now sunk beneath the Kinzua Dam reservoir; to the Mohawk lands commandeered for the Club de golf d’Oka and the Musqueam lands locked in Vancouver’s Shaughnessy Golf and Country Club; and to 50,000 acres of Taos Pueblo Indian land confiscated by Teddy Roosevelt to create the Carson National Forest.

Given the marshalling of so many instances and their ongoing nature—the Shaughnessy golf club will not revert to Musqueam control until 2033—it is understandable that King positions land as such a polarizing resource. “For non-Natives,” he writes, “land is primarily a commodity, something that has value for what you can take from it or what you can get for it.” Even more baldly: “Sure, Whites want Indians to disappear, and they want Indians to assimilate, and they want Indians to understand that everything that Whites have done was for their own good because Native people, left to their own devices, couldn’t make good decisions for themselves.” But more than that? “Whites want land.” He is quick to point out that the brush he is using is broad, but there is a lot of canvas to cover, a lot of wrongs to redress. And it is hard to dispute arguments like “the Alberta Tar Sands is an excellent example of a non-Native understanding of land,” even as the prospect of billions shakes the moral foundation of not just Europeans but every Canadian adjacent to the money pit that is Alberta.

a grand structure, a national chronicle, a closely organized and guarded record of agreed-upon events and interpretations, a bundle of “authenticities” and “truths” welded into a flexible, yet conservative narrative that explains how we got from there to here. It is a relationship we have with ourselves, a love affair we celebrate with flags and anthems, festivals and guns.

Writing history, he says, is like herding porcupines with your elbows. Writing a novel, by contrast, is like buttering warm toast. Part of this sense of ease must come from the way King sees stories. By contrast to the closely organized and guarded record of history, stories can be, he suggests, mutable and humble, disorganized and fractious. As a result, although The Inconvenient Indian is “fraught with history”—he told The Globe and Mail he put 470 dates in its 266 pages, and I have no reason to doubt him—“the underlying narrative is a series of conversations and arguments that I’ve been having with myself and others for most of my adult life … A good historian would have tried to keep biases under control. A good historian would have tried to keep personal anecdotes in check. A good historian would have provided footnotes. I have not.”

The book conjures images of Don Quixote in headdress and blanket tilting at hydroelectric dams. (The author’s sense of outsize drama is contagious.) King apologizes for the guns reference, by the way, allowing elsewhere that we have dispensed with guns and bugles—although in all other senses progress has been poor. “While North America’s sense of its own superiority is better hidden, its disdain muted, twenty-first-century attitudes towards Native people are remarkably similar to those of the previous centuries.” This is clearly not untrue: by any measure we have underserved our Native citizens. To choose just one metric: Aboriginal Affairs’ 2009 assessment of water and wastewater systems characterized 39 percent of reserve water systems as at high risk for poor health and another 34 percent as medium risk.

This is an opportune moment to question the project that is The Inconvenient Indian. Is it counter-history? Cri de coeur? A settling of accounts? “There is a great deal in The Inconvenient Indian that is history,” King writes in the prologue. “I’m just not the historian you had in mind.” Question begged: “you” who? The book’s overall tone, its retelling of vignettes like the blasting of Mount Rushmore and the Oka standoff, suggest he is aiming for the broadest of readerships: schoolkids, book clubbers, radio phone-inners. The traction of the Idle No More movement, and its specific message that early land negotiations were enacted in good faith but subsequently dirtied and dismissed, suggests that King is not wrong to pitch an alternate “once upon a time” history of this land to the same broad audience that for four years enjoyed his Dead Dog Café Comedy Hour on CBC Radio.

King’s greatest accomplishment through his writing—and, I would guess, his decades of teaching—is the broad compassion he shows to all his readers. The sorrow and rage he feels at the mistreatment of North America’s First Peoples sits comfortably alongside an acknowledgement of humanity’s ongoing foibles and myopia. For each hero defeated—each Louis Riel and Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull and Gabriel Dumont—he mourns equally the broader, ongoing blindness of a dominant culture that has settled for Middletons and Custers: “I simply have difficulty with how we choose which stories become the pulse of history and which do not.”

The sad truth is that, within the public sphere, within the collective consciousness of the general populace, most of the history of Indians in North America has been forgotten, and what we are left with is a series of historical artifacts and, more importantly, a series of entertainments … an imaginative cobbling together of fears and loathings, romances and reverences, facts and fantasies into a cycle of creative performances, in Technicolor and 3-D, with accompanying soft drinks, candy, and popcorn.

Dead Dog Café was meant to countermand this romantic hogwash. Green Grass, Running Water was, too. And The Inconvenient Indian, in its cross-boundary, era-leaping, fast-and-loose trickery, is as well. Kindhearted, King fixes our gaze on our own actions—whoever “we” are on this continent—while whispering in our ears that the story, although tragic, is far from over. In The Truth About Stories, he included this wish: “If I ever get to Pluto, that’s how I would like to begin. With a story”—for stories are the alpha and omega, the wellspring of creation and the homage to destruction. Ten years later, The Inconvenient Indian does amend his wish: “If we ever get to the stars and find a new world that can support our version of life, and we decide to terraform the place, it would be best to keep the Department of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Indian Affairs as far away from that planet as possible.”

John Burns is the editor-in-chief of Vancouver magazine, a city staple published in traditional Musqueam territory since 1967.