In “And Neither Have I Wings to Fly”: Labelled and Locked Up in Canada’s Oldest Institution, Toronto writer Thelma Wheatley has given imaginative life to a largely forgotten chapter in Canadian history. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, spurred by eugenicist ideas popular throughout the western world, Canadian politicians, social workers, nurses, physicians and parents participated in the incarceration of thousands of children and adults labelled “mentally defective.” Many spent years of their young lives housed in inhumane conditions, separated from family, labouring without compensation in institutional kitchens, wards and laundries, and facing brutal treatment at the hands of staff. Some were sterilized without their knowledge or consent.

Not a purely academic treatment of eugenics, this book is part memoir, part treatise. Wheatley threads her larger narrative through the story of “Daisy Lumsden,” a teenage resident from 1959 to 1966 in the Ontario Hospital School in Orillia, and of Daisy’s extended “Hewitt” family, many of whom also spent time at “Orillia.” By juxtaposing the profoundly marginalized lives of the Lumsden and Hewitt kin with those of the politicians, professionals and public administrators whose judgements doomed Daisy and her relations, Wheatley renders the broader story profoundly personal and underscores the deep injustice of this history. Extensive archival research and a skillful integration of relevant scholarship shores up Wheatley’s narrative construction. The result is an important and accessible piece of Canadian disability history and worthwhile reading for those interested in the historical overlay of medicalization, human rights and the plight of vulnerable people.

Although the final chapter of Daisy’s patient history touches on the unbounded possibilities of late 1960s permissive society, this book—and Daisy’s story—are dominated by notions of heredity born in the late 19th century. Sir Francis Galton, an Englishman and cousin of Charles Darwin, created the pseudo-science of eugenics in the 1880s, a school of thought that regarded the human race as a vast breeding stock. In the eugenicist universe, reproduction and the fate of the nation were inextricably entwined: based entirely on the accident of birth, eugenicist theory categorized an individual as either “superior” and a worthy citizen or “unfit” and a liability to the nation. The title of the broadly influential 1904–08 British Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-Minded sums up the thrust of the movement.

Canadian eugenicists looked primarily to Britain for leadership, although ideas from the United States were also influential. Wheatley connects the lives of Daisy and her kin, real and imagined, to luminaries in the Canadian medical establishment who built their careers on eugenicist foundations. Dr. Helen MacMurchy, famous for her Little Blue Books and other maternal health initiatives, was front and centre in the Canadian eugenics movement. Wheatley follows MacMurchy as she traverses the incalculable divide between her Rosedale home and the slums of Cabbagetown where Daisy’s extended family resided, taking along her beef tea and the sure belief that education, race and class rendered her superior. We meet the energetic Dr. D.K. Clarke, first professor in the University of Toronto’s Department of Psychiatry, and Dr. Clarence Hincks, psychiatrist and founding director of the Canadian National Committee for Mental Hygiene (later the Canadian Mental Health Association).

Dave Barnes

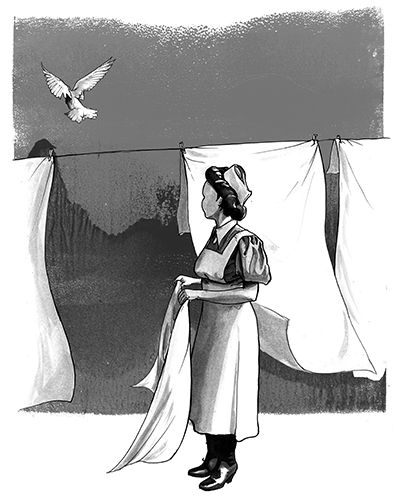

The institution at the heart of Daisy’s story is the Orillia Asylum for Idiots, established by the province of Ontario in 1876 to house feeble-minded youth considered a danger to society and a draw on the public purse. Renamed the Hospital for the Feeble-Minded in 1932 and the Ontario Hospital School seven years later, the consistently underfunded and overcrowded facility depended on the unpaid labour of generations of children and young adults like Daisy, her mother, Ella, and two uncles, who collectively provided 16 years of work cleaning Orillia’s lavatories, changing bed linen and washing laundry.

Abuse and neglect characterized the world of the institution. Inspection reports and recollections, presumably from Ella and Daisy, provide portraits of limited lives, systematic humiliation and outright cruelty. The book presents small kindnesses from staff as a rarity. The sexual abuse of young male residents appears to have been commonplace. Daisy’s friend Eddy shared graphic reports of being gang raped in the communal showers by older male inmates and molested by an attendant during a late-night trip to the toilet. We are left to imagine the life-long pain and suffering endured by former Orillia residents.

In Canada, eugenicist thought gave credibility and direction to establishment concerns about immigration, urban poverty and untamed female sexuality. Keeping company with MacMurchy, Clarke and Hincks in interwar Toronto, we find ourselves deep down the eugenicist rabbit hole. Immigration, taught to us in school as the cornerstone of Canada’s national growth, in fact allowed “inferior stock” from Ireland, Eastern Europe and Asia into the country. Mothers’ pensions, pioneering social welfare legislation of the period that gave some widowed and deserted mothers a monthly stipend, were condemned by some as merely encouraging the mentally defective to procreate. Perceiving poor girls and young women from a eugenicist perspective, everything from a fondness for the dance hall to early sexual relations with a family member became clear evidence of mental and moral degradation.

The family histories of the Hewitts and Lumsdens demonstrate that this is not just a Canadian story, but needs to be appreciated as an imperial project. Daisy’s beleaguered parents were both products of late 19th- and early 20th-century youth immigration schemes, which relocated more than 100,000 impoverished English children to near-certain servitude in the New World. Her grandfather was sent out as an indentured labourer for an Ontario farmer, while her grandmother was raped by a son in the Toronto home where the immigration agency had placed her as a maid. This is another aspect of the historical pattern where children cut loose from families are particularly vulnerable to ill treatment, as they were at Orillia and in infamous American experiments on hepatitis at the Willowbrook State School in New York and on stuttering at an Iowa orphanage. Closer to home, we are just finding out about nutrition experiments by the federal government done on aboriginal children in care in the late 1940s.

The deeply gendered elements of Daisy’s story should also be appreciated. Mentally defective women were regarded as doubly dangerous, for it was believed that their offspring would inevitably be feeble-minded. Ready access to birth control should have been obvious solution, but there was a strange double-think at work in this regard that still lingers in attitudes about abortion rights. Concerns about untamed female sexuality (and procreation) are a subtext in the case files of both Daisy and her mother, but medical personnel disregarded reports from Daisy of repeated sexual abuse from her mother’s male partner. We learn later in the book that this abuse was intergenerational: Daisy’s mother was herself molested by an older brother. It does not appear that sterilization, legal from the 1930s to the ’70s in both Alberta and British Columbia, and practised quietly at Ontario mental health institutions, was ever considered in their cases.

Girls and boys consigned to Orillia appear to have been primarily filtered through state educational, social welfare and public health agencies. Poverty, parental neglect perceived or real, delinquency perceived or real, a stutter, squint or dull expression—any of these could steer a child in the direction of Orillia. The Stanford-Binet intelligence test provided a hierarchical shopping list of labels: dull normal, moron, imbecile and idiot. These eugenicist labels held great authority. Under Canadian law only those deemed imbeciles and idiots (feeble-minded) were to be institutionalized, although the moron class, with their worryingly “normal” appearance and lax moral standards, were thought to comprise a greater hazard to the well-being of the country.

Such measures of intellect were deeply biased, rooted in cultural and class norms. Undergoing intelligence testing in 1929, five-year-old Ella Lumsden (Daisy’s future mother) did not recognize “apple” or any other of the food items of the picture vocabulary exam administered by a psychologist at the Toronto Psychiatric Hospital, but she found a rat in the “Mutilated Pictures” quiz. Three years later she failed to react to the picture “Birthday Party” but identified “Wash Day.” There is no indication in the case files used for this book that the social workers, psychologists and public health nurses that dealt with the Hewitt and Lumsden families ever viewed Ella’s test results through the lens of acute poverty.

Eugenicist thought infused early Canadian social welfare and public health systems. Surviving case files make evident the importance of structural determinants in shaping the lives of the Hewitts and Lumsdens, but the professional voices in these records demonstrate that the family’s situation was framed by moral rather than material concerns. In the winter of 1928 the Hewitts were living on the $14/month of Henry Hewitt’s soldier’s pension and had just used their last chair for firewood. Their social worker was not lacking in compassion, but in the end four of their children were removed from the penniless family: three were incarcerated in Orillia and a fourth was sent out for adoption.

Our current federal government favours the history of wars and great Canadian endeavours. “And Neither Have I Wings to Fly” is a very different story of our national past. Wheatley presents an analysis of societal fault lines formed when powerful professionals grabbed hold of an ideology that rationalized controlling vulnerable youth under the guise of helping them. The parallel to First Nations residential schools, the “Sixties Scoop” of aboriginal babies and the case of Duplessis’s Children is obvious. Taken together, these are vast historical catalogues of institutionalized injustice, but personal stories render the incomprehensible real. Velma Demerson was 18 in 1939 and pregnant by her Chinese immigrant fiancé when her parents and the police cooperated to convict her under an antiquated 1897 law of “incorrigible” behaviour and incarcerate her in Toronto’s Mercer Reformatory. Subjected to painful vaginal surgeries in a search for a gynecological basis for her immorality and stripped of her Canadian citizenship, Demerson lost custody of her son.

Difficult, unsettling pasts, stories of injustice and damaged lives: these are sites where an active, engaged perspective like the one that Wheatley employs can help Canadians appreciate current manifestations of these disturbing legacies.

And shouldn’t history shake us loose from complacency and direct us toward informed -compassion?

Daisy Lumsden requested legal access to her case records from Orillia, persuading her mother to do the same. She pulled Wheatley, a church acquaintance and writer, into her quest for the truth. The final chapters of the book detail her subsequent involvement in a class action lawsuit against the province of Ontario. But the most important truth for Daisy was uncovered in the storied layers of her past, a risky place for anyone, but particularly for a child given by her parents into the care of the state. And here she found a gift. Her parents and maternal grandfather—flawed caregivers that they were—never acquiesced to the power of medicine and the state to catalogue, condemn and own their child. Henry Hewitt, Ernie and Ella Lumsden repeatedly travelled from Toronto to Orillia to visit Daisy. Retaining legal council, they successfully secured her release in 1966.

History, as this book elucidates, holds a dual capacity for emotional healing and social justice—understandings of the past not commonly included in the historian’s toolkit. I ran straight into this possibility, however, in a recent documentary project, The Inmates Are Running the Asylum. Created collaboratively by a rag-tag group of long-term mental health service users, academics and enthusiastic youth, our film follows the story of Vancouver’s Mental Patients Association—the radical and startlingly successful peer support organization that emerged in 1970/71 as a response to the tragic limitations of early community mental health. This work has included powerful moments of personal and political alchemy for the MPA founders and, like the book reviewed here, The Inmates project demonstrated that “memory work” and giving voice to remembrance is an essential democratic act. Historians interested in employing their craft in the fields of reconciliation and social justice can thus take away important lessons from “And Neither Have I Wings to Fly.”

Canadians would like to imagine that the violations recounted in this book are stories from the past. But can we jettison eugenics to the historical scrapyard of regressive public policy and junk science? I would suggest not. I offer two pieces of evidence that the eugenicist mindset still lingers in professional practice and public policy.

First, there is the recent publication of the American Psychiatric Association’s influential Diagnosis and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, where hoarding, persistent irritability in children and grief at the loss of a loved one can now count as mental illness. Clinical criteria for many illness categories listed in DSM-5, we learn, are based on normative social expectations. At the same time—and here again I glimpse the ghosts of MacMurchy, Clarke and Hincks—DSM-5 presents mental health patients as people whose psychological difficulties are rooted in a fundamental biological flaw. Yet surely this is a logical contradiction, for there is not a single physical test for any of the diagnoses listed in the volume’s 991 pages.

Second, I would reference the national five-site At Home/Chez Soi study, the $110 million brainchild of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2009–13), created to “collectively develop a body of evidence to help Canada become a world leader in providing services to homeless people living with a mental illness.” This randomized control study purposefully left half of its vulnerable participants homeless to substantiate something that we already know—mental well-being and a place to call home are intimately connected.1 Imagine a similar research study dividing residents of High River, Alberta, flooded out of their homes in June into two groups, one being rehoused with financial and social support and the other cut adrift to fend for themselves. I doubt that Canadians would find this acceptable, not only because of the hubris of “scientific” experimentation, but also because the people of High River are Just Like Us, citizens with families, jobs, real estate. The At Home experimental subjects are, like Daisy, individuals who are regarded as less than citizens because they exist on the margins of society. They are Other. Orillia would not have existed without this mindset. Nor, I think, could At Home/Chez Soi.

Notes

1 There has been limited critical analysis of the At Home/Chez Soi project. For an exception see Cindy Patton’s “Can a Research Question Violate a Human Right?: Randomized Controlled Trials of Social-Structural Conditions,” published in 2012 at <www.socialinequities.ca/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/Patton-2012-CI-Paper-Can-a-research-question-violate-a-human-right.pdf>.

<p><strong>Megan J. Davies</strong> is a professor in York University’s Department of Social Science and a British Columbian social historian. Her research interests include madness, old age, social welfare, rural medicine and alternative health practices.</p>