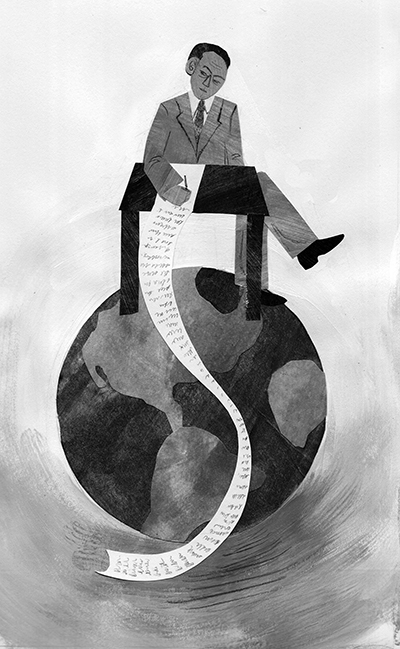

O.D. (Oscar) Skelton was the seminal figure, working closely with two contrasting prime ministers, who shaped an autonomous Canadian foreign policy, moving Canada away from a subaltern role within an imperial system geared mostly to London’s interests. His monumental tenure as undersecretary of state for external affairs from 1925 to 1941 would be unthinkable today, as would his modus operandi.

The Carleton University–based editor of O.D. Skelton: The Work of the World, 1923–1941, Norman Hillmer, is a doyen of Canada’s diplomatic historians, with deep knowledge not just of Ottawa’s archives but also of the workings of government, experienced at first hand from 1980 to 1990 as senior historian at the Department of National Defence. This valuable volume, which reproduces memoranda, letters and diary entries, brings Skelton into sharp focus in an extensive -introduction.

Skelton is known partly for his central role in creating a Canadian foreign ministry and for recruiting the government’s most famous generation of foreign service officers (including L.B. Pearson). Happily, this volume focuses primarily on Skelton’s policy preferences, centred on a meaningful role for a fully independent Canada on the global stage. On this, he saw it as his abiding mission to keep his prime ministers (inclined to occasional emotive outpourings of support for the Empire) on the straight and narrow.

Skelton, a Liberal, managed his greatest tactical coup in surviving a transition from the Mackenzie King governments of the 1920s (interrupted by a brief Conservative interlude under Arthur Meighen) to the very different regime of the Conservative R.B. Bennett (1930–35), who was much more inclined than King to cleave to London’s causes. Although King mostly supported Skelton’s views and proposals, at times he quailed at the relentless onslaught of his undersecretary’s advocacy. As for Bennett, in spite of their very different views, he records in a 1941 note that he had grown “very fond” of Skelton. It is a tribute to Skelton that most Canadians today would agree with his key objective—in a different time, of course—of freeing this country internationally from the delusions, ambitions and schemes of waning imperial Britain.

Shantala Robinson

Like so many highly successful figures, Skelton was a complex personality. While his diary entries cast him as bestriding the globe, in letters to his wife, Isabel, his vanities, trials, tribulations and ambitions leap out at the reader. His self-belief was absolute and his mission in shaping Canadian foreign policy he grandly described as “the work of the world.”

Skelton’s scorn for a Europe that had not managed to keep itself from plunging into the Great War of 1914–18 was mirrored by well-founded fears that it would drag Canada back into war soon enough. He struggled hard, not always successfully, to prevent Canada from committing itself to threatening positions within the League of Nations, for example against Mussolini’s march of folly into Ethiopia. He also adopted a low-key approach to Canada’s position on Japanese aggression against Manchuria, privately critical though he was of Japan’s behaviour.

To read Skelton’s impassioned memoranda to the prime minister, which King often read out to Cabinet, suggests both elements of continuity and a great deal of change since his day.

The Second World War wrought profound change globally, much more than did the murderous first. Above all, it hastened decolonization, produced efforts to unify Western Europe in what has become an expanded European Union and generated a sustained spurt of strong economic growth in the western world, soon replicated in Japan, then in the “Asian Tigers” and now in China. New conflicts emerged, most lastingly in the Middle East. The Cold War broke out, with the Soviet Union empowered by its heroic struggle against Hitler’s aggression, and Stalin determined to fashion a significant Soviet sphere of influence, of which Vladimir Putin’s yearning for a Eurasian Union today is an echo. Economic development of the former African, Asian and Caribbean colonies became a shared international preoccupation. (Only years earlier, in 1944, none other than John Maynard Keynes had described a proposed meeting including a number of developing countries as akin to “a monstrous monkey-house.” ((Letter from John Maynard Keynes to Sir David Walley, March 30, 1944, cited in The Collected Writings of John Maynard Keynes, Volume 26, Activities, 1941–1946: Shaping the Post-War World, Bretton Woods and Reparations, edited by Donald Moggridge (Macmillan, 1980), page 42.)))

Canada, at the height of its international power and influence in 1945, was involved in post-war arrangements in Europe and to a lesser extent in Asia (not least through the Korean War). Skelton would have appreciated the creative role that Canadian politicians and diplomacy played in helping to engineer Europe’s post-war prosperity and stability through a web of multilateral institutions and partnerships. He worked hard for the deeper and more mature relations that emerged in the later 1940s and ’50s between Ottawa and Washington, quite independent from United States–United Kingdom ties. In spite of occasional sharp disagreements (for example, over Vietnam and Iraq) aggravated by philosophical and temperamental differences between several U.S. and Canadian leaders, Washington increasingly viewed Canada as its most reliable—if at times irritatingly moralistic—ally beyond Britain, which it often found annoyingly superior.

Skelton’s tireless work to build up External Affairs laid the foundations for the rapid expansion during and after the war of Canada’s network of diplomatic missions throughout the world. Several of those he recruited, who regarded him with admiration in spite of his incapacity to delegate, went on to lead this effort.

Skelton’s relationship with two such different prime ministers speaks to the importance prime ministers then attached to strong policy advisors from within the public service. His experience over 18 years rapidly provided him with unrivalled credibility. Today, deputy ministers turn over at rates that often preclude in-depth mastery and personal dominance not so much of departmental files but of the wider field within which federal policy operates. It is not clear that anyone at the political level pays much heed to their views. (One federal minister told me recently that the government received its policy input “through other channels.”)

So, are deputy ministers in Ottawa today irrelevant? On the contrary, they are vital—as managers of process and programming, implementing policies into which they sometimes have limited substantive input. For them, systems management is “in,” accompanied by its vocabulary, fads and vagaries. Skelton would never have made it far in this world, nor would he have wanted to.

In Skelton’s day, key diplomatic forums were few, the negotiators senior. Skelton spent weeks abroad at a time, generally in the major European capitals, staying (like his foreign counterparts) in the grandest hotels and dining with the greatest names. In those days, the work of the world was conducted by a select few, who lived quite large when on the road and seas.

Diplomacy has migrated down scale since then, along with public service more generally. The overall cost of vastly expanded governments today excites indignation over expenses of all sorts among heavily taxed publics. Today, foreign service staff and other public servants shop around for hotel deals on Expedia. As to offering hospitality to key connections with the power to affect Canada’s interests (often in return for hospitality received), today’s dinner bill might be tomorrow’s $16 orange juice news item—an inhibiting thought. That much exchange and negotiation internationally is conducted over meals, whether Canada approves or not, is an inconvenient truth. In its obsession with government waste, Canada is both particular and simultaneously part of a wider global trend in which private sector activity and leadership is lionized (no matter how criminal it turns out to be) while public service is seen by many primarily as a waste of taxpayer funds. In vote-seeking mode, politicians too often play to this prejudice.

The drivers and the mechanics of foreign policy formulation are radically different in Canada today than they were in Skelton’s time. Canada was then defined by two founding nations. Today, pandering on foreign policy for electoral gain to any segment of Canada’s admirably diverse population is fair game for any party smart enough to figure out the winning angles. The Liberals used to excel at this. The Conservatives have captured the ball with great skill. Curiously though, underpinning these manoeuvres, at the very heart of Ottawa today lies a strain of nostalgia for and allegiance to the Anglosphere, symbolized most prominently by the monarchy but also by veneration for wars fought with Anglosphere comrades in bygone eras.

Canadian public service work is both similar to and altogether different from what Skelton experienced and sometimes invented. Skelton personally wrote long memoranda to the prime minister on international developments and their implications for Canada. He invariably recommended a clear course of action. Today, such advice would be de trop. For many years now, senior officials have hardly written at all. Rather, consensus-oriented documents rise up from the bowels of departments, are further diluted by interdepartmental consultation, make their way through often stupendously bored Cabinet committees to the status of decisions that are often unfunded and thus come to nothing. Staff rarely influences Canadian foreign policy. The prime minister always mattered. Now, on foreign policy, only the prime minister really matters.

I suspect Skelton wrote so prodigiously largely in order to sort through his thoughts. The self-editing process, which he valued, aims to produce clarity and coherence. This has largely been lost, with platitudes, political correctness of the hour and safe opinions replacing sharp, potentially controversial thought. Occasionally, policy entrepreneurs—and the senior public service ranks always number several of them—are able to cut through the gibberish and turn it to the advantage of their own preferences or the national good. But, overall, Skelton’s approach expired decades ago.

Was he a heroic figure? He certainly was a “great Canadian.” Skelton’s introverted nature concealed a seriously overdeveloped ego. But this is often the case for game changers. Chance, intellectual acuity and his own industry provided him with the means of his ambition, for Canada and for himself. He fit ideally with his era, seized his opportunity and made genuinely historic contributions to our country. This volume is an unsentimental and deserved tribute to his qualities and achievements.

David M. Malone is a former Canadian high commissioner to India and a former rector of the United Nations University, headquartered in Tokyo.

Related Letters and Responses

Andrew Griffith Ottawa, Ontario