It was, in its day, the largest construction project in the world, requiring removal of more earth and rock than the Suez Canal. An area the size of Manhattan was flooded, forcing the relocation in the name of progress of thousands of residents. The most modern construction techniques were employed, including new organizational systems and the first computer in Canada.

As a nation-building exercise, it might have been on a scale with the epic enterprises of Canadian history. But the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project is now something of an embarrassment—an opportunity lost or perhaps even a strategic mistake of immense scale.

That perspective was hardly on display in 1959 when Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower, presided over opening celebrations and boarded the royal yacht Britannia for a five-hour escorted cruise through the locks. No fewer than 1.8 million people had visited the megaproject leading up to that auspicious day.

In the 19th century, pre-Confederation Canada and the United States built canals to avoid the rapids on the St. Lawrence and to avoid coming too close to a border that was not necessarily peaceable. But in the mid 20th century, Canada and the United States, in the apt words of author Daniel Macfarlane in Negotiating a River: Canada, the U.S. and the Creation of the St. Lawrence Seaway, “turned the St. Lawrence Valley into a hybrid waterscape that blended the mechanical and the organic, with hydro dams and locks … by which the river could be perfected and its water utilized to its full potential.”

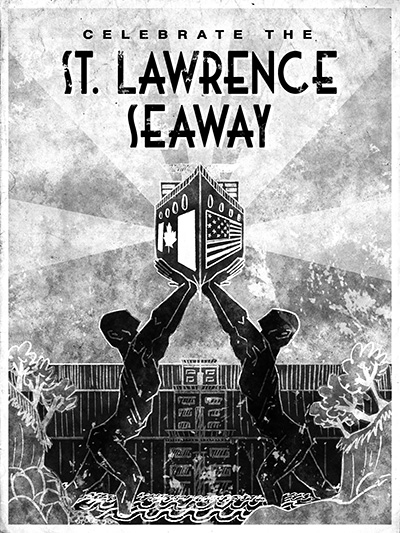

Tyler Klein Longmire

We did it together. For decades, the Seaway stood as the largest transborder water control project ever undertaken. And yet, the 50th anniversary came and went in 2009 virtually unnoticed. Why? And what can be learned from this finely honed book about the challenges that face Canadian development on our shared continent?

Macfarlane, a visiting scholar in the School of Canadian Studies at Carleton University in Ottawa, has mined the archives well in researching a story largely forgotten. His efforts are particularly apparent regarding Canadian and U.S. political machinations over the Seaway—which went on for decades—and the interactions between key Canadian and U.S. actors who often seemed to be talking past each other.

As is so often the case, Canada and the United States came at the issue from different perspectives. For Canadians, the St. Lawrence was (and to some extent remains) a leitmotif for the country and its evolution. Jacques Cartier gave the river its modern name in 1535. European explorers saw the river as an “obstacle-filled water highway into the heart of an undiscovered continent,” Macfarlane writes. Canada itself took shape around the St. Lawrence, historian Donald Creighton posited in his influential interpretation of the country known as the Laurentian Thesis. The St. Lawrence was nothing less than a lifeline for fledgling settlements on the cold side of the border from an industrializing power. And, in any case, most of the river lies exclusively on the Canadian side.

For Americans, the St. Lawrence was just a river, and a fairly minor one, not even as important in the “North Country” as the Hudson and Albany rivers that guided citizens to the opportunities of the eastern American seaboard. Macfarlane puts it bluntly, particularly for a Canadian audience: “the St. Lawrence River was Canada’s front door, but America’s back door.”

Negotiating a River examines the construction of the Seaway from multiple perspectives. It delves into the submergence and destruction of the nine “lost villages” on the Canadian side. (Far fewer Americans lived on the international stretch of the St. Lawrence and, thus, fewer needed to move.)

This was the era of progress, of modern state engineering, and those who stood in the way were thrust aside. The American personification of this perspective was Robert Moses, the human battering ram who took an outsized role in U.S. post-war development and played no small part in the Seaway. In a speech at Ottawa’s Château Laurier Hotel during construction, Moses admitted that the sheer audacity of the megaproject might appear like “the classical tragic Greek idea of ‘hubris’” but that “the vaulting ambitions of two democracies” demanded progress on such a scale.

Canadian riverside residents were treated better than their American counterparts, but Macfarlane raises reasonable questions about the fairness of the process. The Ontario government body that oversaw compensation discussions with communities and individual landowners was characterized by one historian as both the pitcher and the umpire. Homeowners were often ill informed of their rights. Families did not necessarily foresee what was to happen to them (one boy told a reporter he would “swim for it” when the waters came) and many just preferred their “old well in the back yard with its moss-covered bucket than modern waterworks,” according to an Ottawa Evening Citizen article quoted by Macfarlane.

Eventually, two new towns—Ingleside and Long Sault—were created along what was to be the new shoreline and whole houses were moved to them using equipment new for its day that drew the attention of tourists and the national media. A total of 22,000 workers from both countries were employed on the megaproject. Scores were seriously injured and no fewer than 42 died during construction of the Seaway, which became known to some as “Cripple Creek.” Inundation Day brought 25,000 observers.

Still, this book is primarily a study of Canada-U.S. relations and how Canada’s oscillating view of sharing a continent with a superpower (draw near to drive economic development, draw away to protect national distinctiveness) played out in this important instance. Negotiating a River adds greatly to the literature of bilateral ties, especially since Macfarlane inhabits the middle ground, neither assuming that good fences make good neighbours nor that common space is necessarily a good thing.

Canada and the United States had been talking off and on about the St. Lawrence since even before their first significant bilateral body was created in 1909—the International Joint Commission, which focuses on water issues. In 1892, Parliament and Congress passed separate motions appealing for improved navigation on the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence. But this historical coincidence masked critical crossborder and domestic differences that retarded progress for decades. There was much activity on the file through the first half of the 20th century, but far less forward motion.

The economic potential of the St. Lawrence simply mattered less to the United States than to Canada. American exporters were well served by existing ports on the east coast and the Gulf of Mexico. And divisions within Canada did not help. The Prairie provinces were skeptical of the benefit to them. They eventually fell in line, but Quebec too stood as an opponent of the initiative until the early 1950s, out of concern for port and trans-shipment businesses in Montreal and Quebec City.

Post-war prosperity changed the calculation. The industrialization of Ontario made the province even hungrier for the cheap hydroelectric power that the St. Lawrence could provide. More broadly, Canada had emerged from the war as a global leader with unprecedented confidence. The time was ripe for a project of global scale, reasoned the federal government of Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. If a protocol with the Americans was not going to bring tangible progress swiftly, Canada had the means to go it alone.

“The idea that the great stream could once again serve as the catalyst for nation building captured the national imagination,” writes Macfarlane. “Canadian newspapers, particularly in Toronto, decried the prospect of the United States ‘buying in cheap.’”

When we think of Canada in the 1950s, we think of two megaprojects—the Trans-Canada Highway and the TransCanada pipeline—which accelerated the evolution of the modern nation. The Seaway is on their scale, although with a twist. Canadian nationalists still decry the cancellation of the Avro Arrow fighter jet project during that era. The Seaway stands, likewise, as an historical might-have-been. What might have happened if Canada had actually acted alone? And what caused the federal government not to do so?

Macfarlane concludes, and it is difficult to disagree, that the Seaway saga and the eventual agreement to move forward hand in hand with Washington may be the most underappreciated aspect of the bilateral relationship in the post-war years.

The St. Laurent cabinet was split on the issue. C.D. Howe, the U.S.-born “minister of everything,” was determined to proceed without the vacillating Americans, as was minister of transport Lionel Chevrier. But at what cost?

The confidence brought by post-war prosperity ran up against the demands of Cold War security, meaning Washington was loath to countenance independent action on its border. Canada was a trusted ally, but U.S. security and economic interests were at issue. Canada, noted external affairs minister Lester Pearson, was “caught between two fires.” Once it became apparent that Washington was intent on participating as an equal partner, however, a joint Seaway came to be seen in Ottawa as almost inevitable.

Were the terms to Canada’s advantage, at least? Eisenhower told his negotiators to go the extra mile for Canada: “When you’re trading with those Canadians, be so fair that you could move on their side of the table and feel comfortable in your -bargaining.”

But St. Laurent may not have been so certain. He is said to have described the deal signed as “the best … of a bad bargain,” although he may have been mistranslated.

Macfarlane thinks it is a fitting conclusion, accurately translated or not.

Does the sovereignty issue—the blunting of the go-it-alone approach—account for the relative lack of interest in the Seaway today? Not entirely, or perhaps even primarily. The biggest factor may be cold, hard cash. The Seaway never lived up to financial expectations, although the $1 billion project came in on schedule. In its first full year of operation, the Seaway carried 20 million tons of cargo compared to eight million on the old St. Lawrence canals. But that was well under expectations and the operation lost money. The low volumes continued through the early years and cargo peaked in the late 1970s.

In a sense, the Seaway was already obsolete when it opened. The rise of container shipping, which makes goods shipments easier to move by varying means of transportation, and the introduction of larger vessels caused the Seaway to be bypassed. The benefits of the hydroelectric dams remain significant to this day, but there seems little doubt that, overall, the megaproject should be considered a cautionary tale.

Macfarlane is blunt in his summation: “Although the St. Lawrence Seaway and Power Project was an impressive achievement from an engineering perspective, and there were certainly economic benefits, in hindsight the project should be considered a mistake.”

What lessons might this raise for the future of Canada-U.S. relations? Two generations later, the Keystone XL pipeline imbroglio is the most obvious point of comparison. Here there are similarities, among them Washington’s tendency to place political calculations above long-term interests even with its geographic neighbour, and the risk of spending huge sums today on investments that may prove anachronistic tomorrow. So, too, are there differences, such as the more complicated political environment that faces decision makers today with the growth of non-governmental organizations and other citizen groups.

More broadly, though, the Seaway saga tells a familiar tale for Canadians of what has been archly referred to as “dealing with uncle.” As is the case today, it was difficult then for Canadian officials to get the attention of American counterparts on an issue of regional importance when the Washington gaze was fixed firmly on the global horizon. Despite Eisenhower’s exhortation for fairness at the bargaining table, the “special relationship” between the two countries so often referenced—at least on the Canadian side—proved to be of limited value given the weakness of institutional linkages. Canada struggled in its familiar position as a “regional power without a region.”

Canada’s frustration about disputes and irritants past and present has often led to demands for “linkage”—to pressure the United States with obstruction on other bilateral issues on which Canada might have greater bargaining clout. The power disparity between the two countries always makes that risky, however. (In the words of an American powerbroker of another era: “Don’t play leapfrog with a unicorn.”) Macfarlane concludes that linkage attempts were “prominent” during the Seaway dispute, disagreeing with other scholars who looked more broadly at bilateral ties during the 1950s. Canada, certainly, walked a tightrope in getting the Seaway built.

“I believe that although the St. Laurent government certainly furthered Canadian-American integration, it did so with some reluctance and in order to advance what it perceived to be Canada’s best interests,” Macfarlane concludes.

It may have been for the best that this was a bilateral enterprise, after all. We made the Seaway together, setting a new international standard. And given the disappointing long-term benefits, the risk was—and is—spread appropriately.

Today, the drive along the northern shore of the river is one of the loveliest in Ontario. One does not necessarily know this is a “manufactured landscape.” During an era when “man” spoke of taming rivers without any sense of irony (or environmental considerations), Canada and the United States came together with the best of intentions. As is so often the case, however, the modern lens does not view things the same way.

Drew Fagan is a former Ontario deputy minister and policy-maker with the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Global Affairs Canada). He is now a professor at the University of Toronto’s Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy, and a Public Policy Forum fellow.