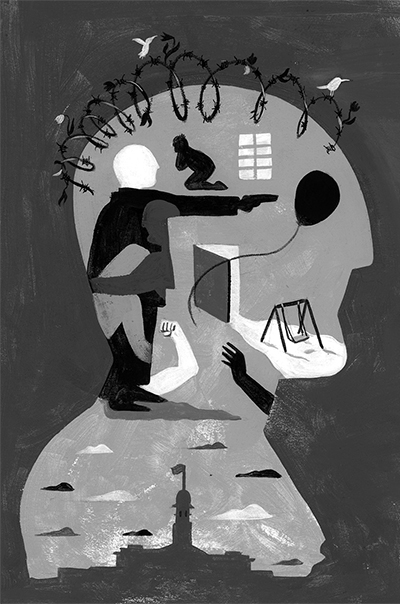

When I first read the synopsis of Gary Garrison’s Human on the Inside: Unlocking the Truth about Canada’s Prisons, I was unsure what to expect. Yet I welcomed the opportunity to read about prisons and prisoners from the eyes of an individual who is not a correctional scholar, staff member or prisoner—someone without an occupational or scholarly investment in the topic, but who has simply developed an interest in the topic and, most importantly, the person imprisoned. A journalist and former editor of the Alberta legislature’s Hansard, Garrison became familiar with maximum security prisons during his work with the Mennonite church as a coordinator of visiting programs. He draws on this experience and the interactions it spurred to remind the reader that prisoners are human beings.

When coming face to face with a prisoner—sex offenders or murderers included—our first reaction should not be fear, says Garrison. Instead we need to be open to their plight and acknowledge the life circumstances that all too often lie behind incarceration. This may make his book seem similar to those of other prisoner advocates, but what makes Garrison’s stance unique is his willingness to reveal his own personal battles, insecurities and anxieties while he showcases the struggles and challenges of the prisoners he meets. His own humanity comes through as much as the humanity of the prisoners he highlights.

That means Human on the Inside is as much a memoir as it is a collection of stories. Garrison shows how the experience of prison shapes a person—something that applies as much to those who freely enter prisons, such as himself, as it does to prisoners. Even those of us who visit prisons to carry on scholarly research end up being reshaped by our acquaintance with life inside. Views of people are transformed; perspectives on the world altered; things one never knew about oneself revealed.

Garrison’s entry into this world is prompted by the stresses of navigating his life after he separates from his partner. To this is added occupational burnout. At his professional job he is trapped in a classic pair of golden handcuffs. “People like me had well-paying jobs we’d been in a long time,” he says, “but if we got tired of them or wanted to change careers, we had little hope of moving to another job with similar pay somewhere else.” He follows the advice of a counsellor who tells him he should deal with the difficult turn of events in his personal life by introducing himself to a new world and to people unlike himself.

Suharu Ogawa

Such a story is far more relatable to the average reader than the tales of the men who eventually call prison their home. Indeed, if it were not, the fascination in popular culture and media with prisons, police, gangs and drama would simply not exist.

Garrison depicts the vulnerable lives of some of the prisoners he encounters. Although sad and perhaps initially unbelievable, stories of dads teaching their sons to inject heroin at age six, of chronic runaways, of abuse and more abuse, of watching a murder or rape and learning a way of life that fortunately many citizens cannot imagine, are common in prisons. I remember bringing a friend I had met when doing interviews with parolees about incarceration and reintegration into an undergraduate class I was teaching. He is now serving a life sentence and talked a bit about himself and prison living as well as the struggles of reintegration. He said his upbringing was a typical one. His family was educated and financially stable, yet he started to run away at age six and had grown up in prison. He then explained to the class that they were lucky to be in university: he had wasted his prime years in a place where “being a murderer was like saying you went to high school”—and more common. Garrison too tells stories such as this, presenting an accurate rendering of the sadness that is imprisonment and the realities leading to criminality.

I wonder, if I’d been beaten by my father, sent off starving to one foster home after another, bullied by other kids in school; if my wife had repeatedly cheated on me, if I’d used alcohol to dull my pain, if I’d had a gun handy when my wife and I had a major fight, am I sure I would’ve made better choices than Roy did? And would I have survived all those years in prison without being brutalized by the place, transformed into someone more violent and uglier than the prisoners I live with?

To which he responds, describing his attendance at Roy’s funeral, “This is where we all end up, I tell myself. When the time comes will I be able to face my own death with as much dignity and good humour as Roy did?”

Garrison does not ignore the perspective of the victims he encounters during his growing acquaintance with prisons and the legal system. He shows the diversity in the views of victims while illustrating how victims’ view of the acts committed against them crucially determines how those acts will affect their lives. Grief cannot be negotiated, but the ability to move past a tragedy and make meaning in life depend very much on how the event is interpreted. Garrison speaks of victims whose lives fall apart, who lose everything from their jobs to their marriages. Some even fear day-to-day living. Conversely, he highlights the views of victims who manage to turn traumatic experiences into survival lessons.

Personal views, character strength and beliefs are equally important in the lives of prison staff. Garrison acknowledges that he has been treated in a range of ways, good and bad, by these individuals, but some of his accounts of these people are touching: “The chaplain asks the guard about the phone call, and the guard starts to weep,” he says when bad medical news arrives concerning one prisoner. “After a few minutes, he wipes his eyes, turns to me, and says, ‘Most people don’t think we care about these guys. But we have feelings too.’”

He also describes witnessing security in prisons becoming increasingly stringent, the growing institutional challenges prison staff face given managerial and Correctional Service Canada policies, and the frequent gaps (intentional or unintentional) between best-practice mandates and how prisons actually operate. He draws attention, too, to the fate of some of the programs designed to help prisoners inside and outside of prison. One is the LifeLine Program, supporting prisoners serving life sentences that was established in 1991 by Correctional Service Canada in partnership with other justice agencies. This much needed and award-winning initiative ceased due to funding cuts in 2012. The institutional context is discussed with enough detail that Garrison’s view of these programs’ utility is easily understood, while he leaves it to readers to form their own opinions about how well the interests of prisoners are served by them.

Given his book’s virtues, it is unfortunate that Garrison mixes up some facts regarding prison-related processes. For example, no person can go directly to a maximum security penitentiary to be held for a federal sentence immediately following arrest, as he at one point suggests. That is because a prisoner does not enter federal custody until he or she is tried and sentenced, and all persons convicted of some select crimes, such as first-degree murder, must be tried by a jury. Thus they can spend years remanded into custody in a provincial facility. Overall, however, such slips to not detract from the overall legitimacy of his book’s central argument and core principles. Furthermore, Garrison acknowledges up front that his work is not a text or scholarly piece. What he does accomplish is to give a wide range of people involved in the prison system a voice, while revealing the vast vulnerabilities of prisoners and the hardships of penal living.

Inside Kingston Penitentiary (1835–2013), by photojournalist Geoffrey James, is a pictorial memoir of the oldest penitentiary in Canada. Established in 1835, it was in operation for 178 years before it closed its doors in September 2013. James’s photographs take us inside the penitentiary’s vast and intimidating structures, with their cold colouring and notorious bold barbwire fencing. We enter first with the perspective of a visitor or staff member. Then we see the setting as a prisoner.

As we are taken through a typical day from before sunrise to after the sunset, candid images of the dreary and decrepit are mixed with glimpses of prisoner artistry and creative renewal—a toilet seat cover made from a blanket and jeans, a towel rod made from some sort of rope. We see how men have been able to make prison their home, sometimes over decades, with decorated cells, acquired “luxuries” and established routines of daily living. The impact of seeing these domestic settings is magnified when we realize the inhabitants are about to be removed, evicted really, from their home, with no choice in the matter.

Such vulnerabilities are difficult to visually document, although they are suggested in James’s photographs of the private family visiting unit with the child’s room and yard, or aboriginal prisoners participating in a change of seasons ceremony. Still, I would have liked to have seen images of the men who have given up, with their stained shirts and lack of desire to keep on living, the shells of men who no longer have hope. The men we somehow need to reach.

There are at least signs of this, especially in the visual cues provided to prison policy and practice. While it may be possible for an outsider to conjure a stark beauty in the prison’s architecture, the imposing buildings with central posts, towers and vast surveillance systems create an aura redolent not of rehabilitation but of violence—a physical reality in which prisoners all too easily become suspect, their trust in each other mislaid, their faith in humanity shattered.

Some of the photographs of the prison’s interior have this same effect: not least the images of the visiting room with its sally port doors and posted regulations of visitation: “You are not to be standing at these windows or any other place in the visiting room, hugging or holding onto each other. You may walk around the visiting room separately with your visitor, but huddling together and hugging or massaging are prohibited behaviours. Please understand that these rules are in place so that we can have a safe and secure environment for everyone. Thank you for your cooperation!”

James’s visual memoir hints at the reputation Kingston Penitentiary gained as one of the hardest places prisoners ever did time in Canada. Yet I found the special stigma tied to this institution missing. Its reputation among prisoners is that it housed only sex offenders. “If he served time at KP, you don’t want to associate,” was the way one prisoner explained it to me; “[because] you know he’s a diddler.” James’s images also fall short in portraying the dire straits of the prisoners who must fear the outcome of their pending transfer. As night falls in James’s pictorial account and the prison metaphorically closes, we are left to wonder if the time these men spend at Kingston ends up becoming a target on their backs.

Imagine the anxiety as these men recognize that a new social order needs to be carved out in a new prison post-transfer. But how can this sort of despair, which Garrison eloquently describes in Human on the Inside, ever be adequately documented pictorially? For James it is easier to capture the brutalities and hardness of the prison and the prisoners. Men who served time in the prison have told me stories about their lives being threatened, showed me their scars and explained the atmosphere of the institution, which James captures by including images of swastikas, profanity and intimidating structural realities.

All this makes Inside Kingston Penitentiary an evocative and, in many ways, effective visual document. But it leaves unanswered a glaring question—one that in Garrison’s literary treatment, too, is only partly addressed. Given prisoners have no choice but to be shaped by their incarceration, what can be done to make prison a more civilized and rehabilitative place? And if there is a way to do this effectively, will these solutions be applied, or must prisons remain mired in social dysfunction, forsaken opportunity and needless loss?

Rose Ricciardelli is the author of Surviving Incarceration: Inside Canadian Prisons.