Mental illness has become a mainstay of modern society. It affects an ever-widening swath of the population and demands the largest share of pharmaceutical marketing attention, as the business of ameliorating unwanted mental suffering grosses billions. In popular culture, this suffering is depicted everywhere from tabloids to blockbusters, from books to billboards, and from celebrity magazines to local anti-stigma campaigns. Yet in spite of this apparently unrestricted proliferation, we often blindly cling to the idea that as a society we are improving.

From our smug 21st-century perspective, the history of mental hospitals and the disordered minds and bodies captured within them represents a bygone era of backward thinking, incarceration and the so-called dark ages of psychiatry when crude interventions such as lobotomies and electro-shock therapies were the best that the profession had to offer people suffering from delusions, gripping depressions or catatonic states of despair.

Kay Parley is a writer with a wealth of experience that can help alter this prevailing view. Her newest book, Inside the Mental: Silence, Stigma, Psychiatry and LSD, dispels the myth of mental hospitals as snake pits by illustrating how they can serve as places where the human spirit finds nourishment. Her story relies on her colourful writing style, her depiction of lively characters and her sympathetic rendering of an often forgotten place—Saskatchewan’s provincial mental hospital at Weyburn. Widely known in local folklore as the Mental, this was where two members of her family lived for decades. It was also the site of her own therapy after she experienced two breakdowns while living in Toronto working for the CBC. Later the hospital even served as her employer once she changed careers and became a psychiatric nurse. This last period she viewed as payback for the care the hospital had provided her for the better part of a year.

As a child, Parley saw the large Victorian hospital as the place that had absorbed her maternal grandfather and her father. She had no childhood recollections of her grandfather, except those she pulled from her mother’s eyes and from the way her mother stiffened when she spoke about him as a stern reverend who struggled to keep up with the changes that overwhelmed their small community during the settlement of the province. Her father had a special place in her heart as a kind man who had been taken away when she was a child and diagnosed with manic depressive disorder. The fancy diagnosis did not hold any meaning for a daughter who missed her father until as a young adult she worried about falling into a similar black hole.

Jenn Liv

After going to school, doing some writing and a bit of theatre, then moving to Toronto, Parley experienced her first breakdown. She plunged into a depression, gripped by delusions and auditory hallucinations. This turn of events siphoned her out of Toronto and returned her to Saskatchewan, where she reunited with her father in the mental hospital. But the reunion was not immediate. The first weeks of her stay were confusing, even disorienting, as she learned the rhythms of the place and was introduced to the patients and staff who lived there.

Historians of asylums have often been critical of the way these places incarcerated people and created rules that numbed the personalities of their inhabitants. Parley’s account reminds us that in spite of the rules and lack of privacy, such hospitals could serve as a home and even a community. On her path to recovery she met friends, enjoyed freedom and earned the trust of staff members who protected and befriended her. She soon found that her therapy blended with her livelihood. In time she became the editor of The Torch, the monthly hospital newsletter, and quickly gained the affection of others for her creative talents as the director of a theatre production. As she began to move freely through the institution, she finally faced her father and met the grandfather she had only ever heard about as a child. In these moments she encountered both familiarity and chronicity, which startled her into the realization that her experiences in the hospital were not altogether typical but instead indicative of the patients who need help before returning to the community. On other wards the hospital was a permanent home. Yet despite these circumstances Parley shows how her father and grandfather retained their characters and commanded respect and dignity. She challenges the prevailing idea that patients were merely locked away and forced to conform to the monotony of a life dictated by rules.

In her tender account of meeting her grandfather for the first time, Parley describes him as a debonair figure, finely dressed, and a man who, despite his decades in the institution, impressed upon her his inquisitive and analytical mind. Known by other patients as simply the Reverend, he inspired warmth and awe in the recovering Kay. Moreover, he made it clear he retained a deep love for his family, despite his formal segregation from them over many years.

The hospital’s superintendent Humphry Osmond believed that LSD offered mental health researchers a rare glimpse inside madness.

Meeting her father presented different challenges. Staff were reluctant to have the two meet, worrying that his chronic state may interrupt her recovery. Seeing him at a Christmas concert, which she had helped organize, and immediately recognizing him despite the years apart, helped to renew her bond with him and further reinforced her idea that the hospital was indeed an extension of family.

After her discharge, Parley remained deeply affected by her stay and devotedly sympathetic to the idea that mental health and illness were but two sides of the same coin. Her stay had occurred in the late 1940s, at a time when local and national attention repeatedly identified Weyburn as one of the worst mental hospitals in the country. Her personal experiences contradicted this claim, but over the next decade her views were amplified as the hospital came under new management and embarked on a freshly empathetic approach to madness.

In 1953, Dr. Humphry Osmond became superintendent and things started changing. Within a few years, Weyburn gained international recognition for making the most significant changes to mental health care on the continent. Osmond introduced LSD into the care regimen and his dynamic approach attracted a lively network of researchers, thinkers and sympathizers as he transformed the hospital from a monument of the state to a self-conscious community for care. The new arrivals included Francis Huxley (son of Julian and nephew of Aldous), who introduced Kay to LSD directly.

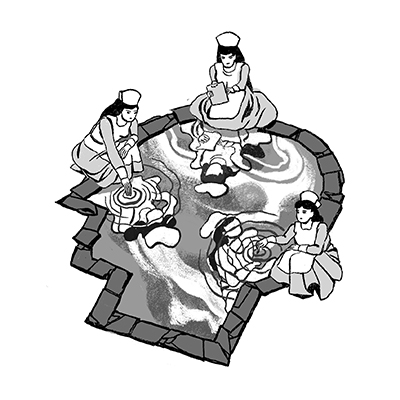

Osmond believed that LSD offered mental health researchers a rare glimpse inside madness. He encouraged staff and researchers to take the drug, with consent and supervision, to generate insight into the perceptions of disordered minds, and especially schizophrenia. Saskatchewan soon attracted curious researchers from around the world, people who were drawn by the psychedelic studies and who were eager to participate in reforming the mental healthcare system. For example, an architect took LSD in an attempt to better appreciate how the hospital design could be improved to accommodate the perceptual realities associated with someone suffering from visual hallucinations. Another arm of research concentrated on treating alcoholics with a single dose of LSD, while the patient remained in the company of a “sitter” or guide who offered both security and sometimes psychotherapy. This form of therapy had dramatic results and challenged contemporary addiction specialists to think differently about how to treat alcoholism using this combination of LSD, psychotherapy and, at times, creativity and spiritualism.

As a psychiatric nurse, Parley was drawn to these experiences and soon demonstrated her skills as a guide. She describes these interactions in vivid detail, displaying her own curiosity and appreciation for the bold experiments with mescaline and LSD that helped to cultivate empathy between staff and patients, further breaking down the artificial barriers dividing health from illness in the hospital community. Her account further underscores the hypocrisy of these divisions, demonstrating instead that mental health and illness coexist in everyone, making both fundamental features of the human experience. Tolerance, understanding and empathy, therefore, lie at the heart of a community of care; Parley displays this feature with sympathy and elegance.

In spite of the notable differences between an LSD reaction and a schizophrenic or psychotic breakdown, the similarities compelled researchers to continue exploring LSD as a tool for generating empathy. Parley revealed her skills as a sitter, one who monitored a subject during their LSD experience by focusing all of their energy and sympathies towards the subject. She meticulously describes how her own experiences with breakdowns allowed her to both relax and focus on the subject at once, letting go of her own inhibitions and concentrating instead on providing emotional comfort to someone whose mind was led through torments of anxiety or into overwhelmingly different perceptions of their surroundings. Here again, Parley’s depiction of these experiences helps to dissolve the boundaries between staff and patient, experience and observation, or health and illness. The blurring of categories that she describes once more humanizes the experience, no matter how bizarre, whether drug induced or produced by psychosis, to illustrate the capacity for madness in everyone.

She convincingly shows readers how experiences at the Mental produced confidence and even rehabilitation among people who benefitted from custodial care.

Parley’s book ends during this period, amid the exciting and even optimistic moments when LSD seemed poised to help overhaul an outdated system. Readers will know, of course, that psychedelic psychiatry did not become part of orthodox medicine, in spite of all of its promise. The fascination with LSD attracted seekers well beyond the medical arena and a growing black market in acid put tremendous pressure on researchers to justify their continued work with the drug while also taking some responsibility for addressing the growing list of side effects, from flashbacks to violent behaviour. Although scientists throughout much of the western world had engaged in LSD research, there was no consensus within professional circles that the drug should remain part of the pharmacopeia of modern medicine; the reactions were intense, hard to manage at times and created unpredictable circumstances. Furthermore, supplies of the drug were difficult to secure with certainty. By the mid 1960s, research units were abandoning work in this area, and LSD hit the streets in dramatic fashion. Self-proclaimed gurus and proselytizers of LSD grabbed media headlines and frightened parents, police and ultimately drug regulators. By the end of the 1960s, the drug had become a prohibited substance and research with psychedelics became illegal.

Inside the Mental is something of an amalgam of Parley’s earlier writings. Not only does it represent a synthesis of these accounts, but it is also a cogent set of reflections on mental illness, hospitalization and perception. Parley avoids the pitfalls of historical cynicism and instead describes a very human experience under a set of circumstances that will be foreign for most readers. She pulls us into a world long closed off to the rest of society, or so we have been led to believe, while introducing us to a cast of larger-than-life characters whose roles at times become interchangeable as they move through the spaces of helper, caregiver, subject, patient and decision maker. By ignoring the titles and concentrating on the people, Parley deftly humanizes what has more readily been depicted in macabre terms. Moreover, she convincingly shows readers how experiences at the Mental produced confidence and even rehabilitation among people who benefitted from custodial care.

In the 21st century as mental hospitals disappear from the landscape and as mental health care becomes synonymous with psychopharmaceutical consumption, these reflections are worth bearing in mind. Parley convincingly and sympathetically highlights the role of community in both embracing and listening to madness, not merely in ameliorating its symptoms, but rather recognizing the value of empathy in human interaction. Her pre–Big Pharma account draws subtle attention to how mental illness was understood at a moment when patient populations overwhelmed the physical accommodations, but nonetheless people forged societies and negotiated with each other to form bonds, break them and eke out a meaningful existence.

Parley ends her book by acknowledging the inherent value of all people in contributing to community: “When I think of the millions of mentally ill humans whose potential was never realized and whose lives were filled with untold misery in so many societies over so many centuries, all I can say is ‘What a waste.’”

Although Parley does not explicitly draw these comparisons, her emphasis on a particular epoch in the history of medicine raises questions about the frontiers of mental health care. In an era where mental illness is now managed by consuming pharmaceuticals, the core experience of madness may be more understood but less tolerated. What are the consequences of investing in a system that focuses on the responsibilities of the individual to stay on their meds rather than focus on a system that invests in the diversity of communities that are better equipped to embrace difference and nurture the kind of creativity that results from negotiating acceptance? Parley’s candid account of her own life and reflections on the experiments in Saskatchewan help to raise these deeper questions about the value or utility of difference, while insisting that cultivating empathy is our best option for designing a more humane future.

Erika Dyck is a professor of history and holds the Canada Research Chair in the History of Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan. She is the author of Psychedelic Psychiatry: LSD on the Canadian Prairies (University of Manitoba Press, 2012).