The regime that was supposed to own the century may not survive the decade.

The People’s Republic of China is now trapped in slow-burning economic and financial crises. These difficulties are contributing to troubling changes in the country’s politics, and those political changes are affecting external policies, pushing the Chinese state in a far more provocative direction. These trends are making an insecure Communist Party of China more repressive at home.

Not long ago, there was a more hopeful outlook. Everyone then said China had passed from its first broad historical era, one dominated by founder Mao Zedong, to the second period, one begun by his successor, Deng Xiaoping. As Deng consolidated control, China passed from Maoism to an era of “reform and opening up.”

Now, however, China is regressing and closing down. Change, driven primarily by economics and politics, has been so fundamental and transformative that the country has passed into a third stage, an especially turbulent and troubling one.

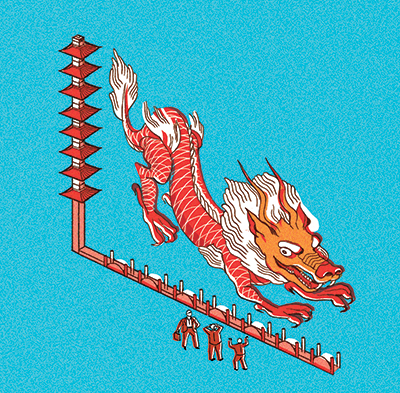

Jenn Liv

This critical transition to the current period began toward the end of the rule of Hu Jintao, the predecessor to current leader Xi Jinping, with changes in the economy. In the so-called reform era, annual growth of gross domestic product averaged about 9.9 percent, but the days of heady expansion are over. The official National Bureau of Statistics reported China’s gross domestic product grew 6.9 percent in 2015.

That official number, however, appears far too high. In the middle of 2015 Citigroup’s chief economist, Willem Buiter, called Beijing’s growth data “mendacious” and suggested the economy was expanding around 4 percent. The Conference Board of Canada’s Harry Wu and Angus Maddison put 2015 growth at 3.7 percent. In the middle of last year, a well-known China analyst was privately noting that people in Beijing were talking 2.2 percent.

And there are indications the economy progressed at an even slower pace, perhaps 1 percent. For example, the best indicator of Chinese economic activity remains the consumption of electricity, and in 2015 electricity consumption increased, but only by 0.5 percent.

Two other important indicators show negligible growth last year. First, imports, in dollar terms, were down 14.1 percent, a clear sign of troubles in both the manufacturing sector and consumption.

Even more damning is price data. Last year, nominal growth of 6.4 percent was well below real—adjusted for price changes—growth of 6.9 percent. And the country’s deflation deepened as the year progressed. It is extremely unlikely that last year there was both robust expansion and worsening deflation.

In one sense, it does not matter how fast China was growing last year. The important point is that Chinese leaders no longer have the ability to prevent the downward trajectory of the economy. Beijing’s monetary stimulus, especially its successive reductions in benchmark interest rates, has failed because there is a fundamental lack of demand for money.

Fiscal stimulus also appears ineffective. Fiscal spending, a good measure of the government’s overall stimulative efforts, accelerated as 2015 wore on. At the same time, officially reported GDP growth trended down.

And two other growth strategies have failed recently: the reckless promotion of share prices beginning in fall 2014, intended to create a wealth effect and to help enterprises pay off debt with new stock, and the botched devaluation of the renminbi beginning mid August, which appears to have been an attempt to, among other things, help exporters.

As a consequence of Beijing’s failed policies, the economy is headed for contraction as Chinese leaders can only slow the pace of descent. Even structural economic reform, something that could create sustainable expansion, has now been delayed too long. Meaningful reform takes years to have a positive effect, and China, in reality, is just months away from entering a downturn.

Chinese leaders talk about reform, but they have implemented little of it. Worse, Xi Jinping has, on balance, forced the country backward by, among other things, closing off the Chinese market to foreigners, creating formal monopolies from already large state enterprises, increasing state ownership of state enterprises and channelling additional state subsidies to favoured market participants. Xi’s draconian measures also prevented the financial markets from functioning properly in efforts to keep share prices and currency values elevated. Moreover, he is pushing national security laws and regulations that look intended to prevent foreign companies from doing business with state and governmental entities.

His signature phrase, the “Chinese dream,” contemplates a strong state, and a state-dominated China is not consistent with the notion of market-oriented liberalization. Unfortunately for China, there are no solutions possible within the political system Xi defends.

China’s economic problems are becoming urgent because China needs to pay off debt. McKinsey Global Institute pegged the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio at a worrisome 286 percent at mid 2014, but the number is surely higher now. In reality, the ratio at this moment could be somewhere in the vicinity of 350 percent—the figure George Soros mentioned in January in Davos—or 400 percent, the conclusion Andrew Collier of Orient Capital Research in Hong Kong reached at around the same time. As a result, China is heading to an impossible-to-avoid debt crisis. “They absolutely have no room left for further debt accumulation,” notes Rodney Jones of advisory firm Wigram Capital.

Observers make the argument that Chinese technocrats would never permit a crash. Yet as China’s political leaders prevent corrections, underlying imbalances are becoming larger and make the inevitable correction far more severe. So China’s next downturn will surely be historic. Chinese leaders will prevent adjustments until they no longer have the ability to do so, and that is when their system will go into free fall.

We do not look to be far from that time. The country’s foreign exchange reserves have fallen far faster than anyone thought possible. The State Administration of Foreign Exchange, the central bank’s custodian of the cash hoard, reported that the reserves dropped $512.7 billion in 2015, and, as large as that number is, it is possible Beijing has been deliberately under-reporting the fall. There is also a concern that China’s reserves are not as liquid as they are represented to be.

Whether liquid or not, Beijing’s reserves now look insufficient. The Washington-based Institute of International Finance estimated net capital outflow last year to be $676 billion. Beijing-based J Capital Research puts the number at $911 billion, and Bloomberg’s estimate is $1 trillion. Countries around the world, like Canada, every day see evidence of capital flight in the form of Chinese investment in real estate and businesses.

People still think a soft landing in China is possible, but by now the odds of a severe adjustment—something on the order of 1929—are increasing fast.

Economic difficulties are deepening while the country’s political trauma continues. China, in short, has yet to complete a historic leadership transition that is changing decades-old patterns of governance.

Deng Xiaoping’s contribution to Chinese communist politics was to reduce the cost of losing political struggles—often death in Maoist times—thereby reducing the incentive to fight to the end and tear the party apart. Xi Jinping has been reversing course, upping the stakes.

According to most analysts, Xi quickly consolidated his political position after becoming the general secretary of the CPC in November 2012. He did this, most notably, with his so-called anti-corruption campaign directed against both high- and low-level officials, “tigers” and “flies” in Beijing lingo. New Chinese leaders have always engaged in some housecleaning, but Xi’s efforts, in truth a political purge, have been unprecedented in scope and duration. The campaign threatens the basis of party rule by unravelling the web of patronage relationships that has, over the course of decades, kept the ruling organization in power.

For almost four decades, power brokers tried to maintain a delicate balance among the party’s competing and shifting alliances, factions, groups and coalitions. Xi, however, has sought to eliminate factionalism, breaking norms designed to ensure stability. As one of his political allies said, his motto is “You die, I live.”

Xi, in many ways, is going back to Mao’s strongman system, “re-introducing fear as an element of rule for the first time since the Cultural Revolution” according to one expert quoted in an article by Daniel Twining in the Nikkei Asian Review. His unprecedented actions look like they mark the end of a quarter century of calm, a time that permitted China to recover from, among other things, Mao’s 27 years of calamity and Deng’s 1989 Tiananmen massacre.

Another round of debilitating leadership struggle is evident from the series of rumoured coup plots and assassination attempts, from the first months of 2012, on the eve of Xi taking power, to late 2014. These rumours, for the most part, look false, but clearly something is amiss in elite circles. The fact that political players spread stories of armoured cars in the centre of Beijing and gunfire in the CPC leadership compound of Zhongnanhai suggests groups are trying to destabilize Xi’s regime. Xi, in short, has pushed opponents so far they believe—probably correctly—that they have no choice but to fight.

Xi’s relentless campaign has been generally viewed as proof he dominates the political landscape. Yet purges are signs of continued weakness in China, not strength. If Xi were as strong as generally perceived, there would be no need for continuing purges.

Why is Xi attacking opponents so hard? Among other reasons, he came to power without the support of any faction he controlled. He appealed to all factions, in large part because he had no faction. Xi, in short, became China’s ruler because he was, at the time, the least unacceptable choice.

But once in power, Xi set out to create a grouping of his own with the military as the core of his support. Xi, also chair of the party’s all-powerful Central Military Commission, is thought to control the People’s Liberation Army, but generals and admirals at the same time wield great influence over him. He cannot say no to senior officers because they are the closest thing he has to a political base, sometimes called the Zhejiang faction, a reference to Xi’s posting to that province before his elevation to Beijing.

The primacy of the military has implications beyond China’s borders. Senior officers, from all outward appearances, are playing an expanded role in policy making. For instance, Hu Jintao, generally considered a weak leader, was nonetheless able to resist military pressure to establish an air defence identification zone over the highly contested East China Sea. But such a zone was declared within a year of Xi becoming China’s CPC chief, an indication top officers began to wield influence as soon as he took over. Now, these officers are making their “military diplomacy” the diplomacy of the country.

The remilitarization of politics and policy is pushing China in directions East Asia has seen before. “The young officers are taking control of strategy and it is like young officers in Japan in the 1930s,” says Huang Jing of Singapore’s Lee Kwan Yew School of Public Policy. “They are thinking what they can do, not what they should do.”

At this moment, China’s officers, from generals to lieutenants, are thinking about what they want, and so have become dangerous, arrogant and bellicose. For the most part, they do not want a closer relationship with the international community. On the contrary, their brand of militant nationalism is creating friction in an arc of states, from India in the south to Korea in the north, where fear of Chinese territorial ambition is growing.

Beijing, as it goes about realizing its territorial ambitions, is trying to appropriate for itself the international waters of the South China Sea. That brings China into conflict not only with the countries surrounding that body of water but also with the United States, which for more than two centuries has defended the global commons.

China, therefore, is not a status quo power. On the contrary, it is trying to fundamentally change the existing international order. Beijing is not just being assertive; its foreign policy has now become counterproductive. China is taking on many others all at the same time, lashing out, aggressively determined to pursue self-marginalizing, self-containing and ultimately self-defeating policies.

As a result, Beijing is suffering one foreign policy setback after another, something evident from the loss of allies, especially in Sri Lanka, Burma and, most recently, Taiwan. At the same time, China’s actions have resulted in the formation of a coalition of countries including India, Vietnam, the Philippines, Japan, Australia and the United States, all worried about China’s direction.

Despite the setbacks, there is little prospect of China going back to more benign policies in the near term. For more than three decades, corresponding to China’s second era, the primary basis of CPC’s legitimacy was the continual delivery of prosperity, and without prosperity the only remaining basis of legitimacy in today’s third era is nationalism. An increasingly virulent nationalism is pushing Beijing into taking worrying actions.

And at the same time, inside China Xi’s policies have become increasingly coercive. Today, for example, there is less permitted speech than there was in the late 1980s.

The broad-based crackdown on civil society has only brought the CPC a temporary reprieve from popular pressure for change. The Chinese people have not abandoned their aspirations.

In 2008, just before the historic Beijing Olympics, my wife and I went back to Rugao, my dad’s hometown, a smallish city in Jiangsu province north of the Yangtze River. We wanted to find out what people thought about the event, but no one wanted to talk about “the government’s games.” Instead, they asked us about the candidates in the upcoming American election, John McCain and Barack Obama, and about how the western constitutional system of checks and balances worked.

One day, the Chinese people will not only have a greater say in their lives; they will determine their own fate.

That day could be soon. China is perhaps the world’s fastest-changing society, and that means the country that will emerge from this decade is bound to be very different than the one we see today.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China (Random House, 2001). Follow him on Twitter @GordonGChang.