In the fall of 2014, just after UberX launched in Toronto, I asked a cab driver what he thought of the on-demand ride-sharing service. Mishearing “Uber” he asked: “Super? What’s that?”

Fast forward to March 2016, and a different cab but the same question. This time, there was no mistaking Uber for anything else and my driver had plenty to say about it and why the city’s mayor was not stopping the company from destroying his livelihood: “John Tory’s wife owns shares in Uber, I’ve heard. That’s why he’s not doing anything to help us, the bastard!”

Conspiracy theories aside (Uber is not currently a publicly traded company), my cabbie’s anger is understandable. In the space of just 18 months, a new digital product had upended a well–established business and the regulatory regime on which it was based, and was now threatening the incomes of thousands of people, including him.

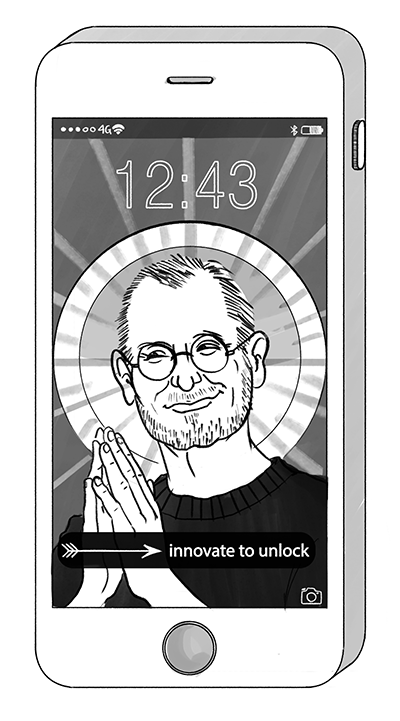

Tyler Klein Longmire

UberX is just one recent example of the changes in business models, consumer value propositions and social interactions caused by digital technologies—a phenomenon commonly known as digital disruption—that are roiling our business, social and political landscapes and having a profound effect on the people living through it. But it is hardly the only one. In the past few years, millions of Canadians have come face to face with digital products and platforms that have replaced established habits in the way we communicate (iPhone), work (cloud services), learn (Coursera), play (virtual reality), watch TV (Netflix), shop (Amazon), research (advanced analytics), make things (3D printing), find work (Indeed), monitor our health (Fitbit) and engage in literally dozens of other activities. Advances in artificial intelligence, digital currencies, robotics, autonomous vehicles and smart networks are poised to further disrupt the status quo.

In his new book, The Third Wave: An Entre-preneur’s Vision of the Future, Steve Case, the founder of AOL, argues that we are entering “a period in which entrepreneurs will vastly transform major ‘real world’ sectors like health, education, transportation, energy, and food—and in the process change the way we live our daily lives,” as the blurb on Amazon says. That is quite a claim and some will accuse Case and his fellow digital evangelists of hubris. (Digital entrepreneurs are not exactly known for their modesty.) Others will point out that technology is always changing our lives, and it is not yet clear whether digital technologies are changing them as much as other -technologies have in the past. Electrification, for instance, in the late 19th century and first half of the 20th century, accelerated the industrialization and urbanization of the west and massively transformed “the way we live our daily lives.” Surely that was a bigger change than YouTube.

These are questions for historians and social scientists to decide. What seems beyond dispute, however, is that people feel the change digital technologies have brought to their daily lives, and intensely so. Merely saying that digital is not as paradigmatic as other technological changes (which may or may not be true) is cold comfort to those whose lives have been turned inside out in the space of less than a decade.

This feeling of dislocation may have something to do with the nature of digital technologies and the speed at which they are changing the patterns of our activities.

At their core, digital technologies are a revolution in information and communications, allowing billions of people to create and share vast amounts of data, almost instantaneously, and certain clever companies and organizations to aggregate and measure that data and market products and services based on it. Like previous revolutions in information and communications technology, this challenges our view of authority. Homer—using a new technology called the alphabet—challenged the clout of the bards and poets who passed on knowledge orally. Gutenberg’s printing press displaced the authority of the monks and priests who wrote and interpreted the bible. In each case, new information and communication technologies empowered a different (and larger) set of individuals at the expense of those who had established themselves as the arbiters of what mattered and what did not.

As for the pace of change, it took more than 60 years to distribute electricity across Canada, and, as Dorotea Gucciardo points out in The Powered Generation: Canadians, Electricity, and Everyday Life, the “changes brought by electricity were gradual, [and] did not occur for everyone at the same time.” (Dorotea Gucciardo (2011), The Powered Generation: Canadians, Electricity and Everyday Life, PhD thesis submitted to Western University.) Contrast that with Google, which has not yet been around for 20 years, or Uber, which is not yet ten years old. No one thinks digital change is occurring gradually.

Rather than a technology we are nurturing into use, our digital world, it sometimes seems, is a revolutionary force that is happening to us, leaving many of our friends, neighbours, co-workers and family members feeling bewildered and vulnerable in its face.

I have come to see digital technologies as an arrow slicing through the air. At the sharp end are those who are leading digital change, the ones who get it. At the back, following in the arrow’s path, are our established institutions, which largely came into being in a pre-digital era, and are scrambling to keep up with this new world. And the shaft of the arrow, unable to direct its trajectory, is the majority of ordinary people, just along for the ride.

At the head of the arrow are the disruptors, those who understand the nature of digital technologies, the economics of digital platforms and the behaviour of digital technology users. These are the people who are quite literally inventing, designing, funding and marketing the products that are shaping our world.

Often describing themselves as optimists or idealists, digital entrepreneurs seem to have a preternatural belief that change is almost always good. “The best of Silicon Valley,” writes Julie Zhuo, product design director at Facebook, “can be captured in two words: of course. Of course the best idea will win. Of course this problem can be solved. Of course you can do it. Change is the road beneath our feet, and in this state, we are curious, eager to learn, happy to debate, fueled by exuberance. It’s grandiose to claim that one is changing the world. But the best of Silicon Valley is the belief that you can — and should — try.” ((Julie Zhuo (2015), “The Best and Worst of Silicon Valley,” The Year of the Looking Glass, July 22. https://medium.com/the-year-of-the-looking-glass/the-best-and-worst-of-silicon-valley-7b337e9a3fd1#.3ejtsjzdb.)) The digital technology venture capitalist Om Malik summed up this mindset best when he titled an essay “What Makes Silicon Valley Special? Eternal Optimism of the Innovative Mind.” (Om Malik (2009), “What Makes Silicon Valley Special? Eternal Optimism of the Innovative Mind,” Gigaom, December 2.)

Writing last fall in Fast Company, Greg Ferenstein, a San-Francisco based author and journalist who has written extensively on the belief system of Silicon Valley, the hot sun of the digital world, says this “breed of optimism or idealism is rooted in a belief that most of humanity have the same goals—and anytime we think we’ve found a good solution toward those goals, there’s always a better solution worth exploring … To disrupt simply means to shed imperfection, exposing ever more perfect solutions beneath.”

This view of change implies that most—if not all—problems can be solved by a better exchange of information. Thus Sean Parker, the internet innovator behind Napster and the first president of Facebook, recently launched Brigade, a social network designed, as the Huffington Post described it, to bring a “profoundly polarized (American) electorate that has lost faith in its institutions back into civic life.” In an interview with Fast Company last year, Parker put it more succinctly: he created Brigade “to repair democracy.” According to Ferenstein, digital leaders “believe that the solution to nearly every problem is more innovation, conversation, or education. That is, they believe that all problems are information problems.” In another article, he quotes Eric Schmidt, Google executive chair as saying, “If you take a large number of people and you empower them with communication tools and opportunities to be created, society gets better.” (Greg Ferenstein (2015), “An Attempt to Measure What Silicon Valley Really Thinks about Politics and the World (in 14 Graphs),” Ferenstein Wire, November 6.)

At the other end of the arrow are the disrupted, those institutions that matured in a pre-digital age and are struggling to remain relevant in the world the disruptors have unleashed.

Some existing institutions are succeeding in this transition better than others but many organizations still rely on pre-digital work cultures, systems and procedures that prevent them from succeeding in the digital era—like traditional cab companies in the face of Uber—and rely on the inertia of their incumbency to stay relevant. Clay Christensen, the Harvard Business School professor and author of The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, has argued that incumbents rarely survive such “disruptive innovation” unscathed. Yet, as a study by the Global Center for Digital Business Transformation has it, about 45 percent of companies it surveyed do not see digital disruption “as worthy of board-level attention.” (Joseph Bradley, Jeff Loucks, James Macaulay, Andy Noronha and Michael Wade (2015), Digital Vortex: How Digital Disruption Is Redefining Industries, Global Center for Digital Business Transformation.)

I am sure banks are thinking of this at the board level. An acquaintance of mine is a senior manager at one of the big Canadian banks, responsible for the rollout of that bank’s mobile (digital) payments system. I asked him who his main competitors were. He told me the names of some start-ups that are moving into this market. Then I asked him about the big guys: what did he think of Apple Pay and Google Wallet? He would not even mention the names Apple and Google, preferring to call them Cupertino and Mountain View. That speaks volumes. In one sense, banks have three core businesses: they hold money, they lend money, they transfer money: deposits, loans, payments. Mobile pay apps are already eating into their payments business. How long before someone—backed by deep pockets—develops an app marketed to the low-hanging fruit in the mortgage market—the straightforward loans that do not require a lot of time, or people, to process? Of course, they will have to figure out the “know your customer” rules and other regulations. But, if you were a bank, would it not be prudent to assume that those deep pockets—if this is a business they want to be in—are already considering how to have those regulations changed?

Beyond banks and the business activities listed earlier, here are a few other examples to consider.

Colleges and universities. A report published by the Ontario government in 2015 on the future of this sector points out that student expectations are changing. (Ontario Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities (2015), “Focus on Outcomes — Centre on Students: Perspectives on Evolving Ontario’s University Funding Model.”) Unsurprisingly, students want to be involved in the development of their studies, new delivery models for courses, more hands-on learning, affordability and value for money—in other words, jobs. Those surveyed do not give particularly high marks to today’s colleges and universities in these areas. Today, however, these institutions can rely on the monopoly they have over the granting of degrees. You want that job? You are going to need this piece of paper that says you graduated.

But what happens when that is no longer the case? Coursera and Udacity are online educational institutions with approximately three million students between them, and growing. The Khan Academy—which now offers some 5,000 courses—is a not-for-profit educational organization dedicated to a “free, world-class education for anyone, anywhere.” What happens when employers determine that a degree from one of these online institutions is sufficient for employment? At that point, our existing institutions of higher learning may be disrupted out of existence.

Politics. As part of what is referred to as e‑-government, e-gov or government 2.0, some governments have begun adapting to the world of digital, mostly in the area of access: citizens want to access public services digitally and their perceptions of government utility are increasingly tied to that measure. Access, however, is only part of the digital equation; including citizens in decision making is another, and numerous studies have shown that people—especially young people—increasingly expect to be able to do this as part of their civic responsibilities. Progress on this culture of participation has been less evident, despite our elected officials’ near-constant announcements of citizen consultations, forums or conversations. In a world where digital technologies make information available to anyone with internet access, government decision–making-as-usual threatens to reduce the legitimacy of political choices.

Political parties. People born as the web was coming into its own in the mid 1990s are now entering their twenties. They, and the generation coming up behind them, are used to making decisions by clicking an app on their phone. They are not dazzled by the magic of the technology; this is just how things are done.

These digital natives, as they are sometimes called, are accustomed to making a single, rather than a bundled, choice to suit their needs. Why would they ever pay for cable and all those channels they never watch when there is Netflix?

Why would this generation not begin to expect that same straightforward choice in the political arena? If 22-year-old Mary is in favour of legalizing marijuana but against running deficits outside of recessions, why does she have to choose from a party system that does not accommodate her positions? Big tent political parties’ brokerage function may not be palatable to digitally sophisticated young people as they become politically active. As Canadians begin to wrestle with electoral reform, we should not be surprised if this becomes an important point among younger voters.

That brings us to the middle of the arrow: ordinary people.

The most apparent consequence of digital disruption on people has been in the labour market. There is a lively current debate as to whether or not digital technologies are leading to productivity growth, with plenty of experts lining up on both sides of the argument. (See, for example, Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War and Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee’s The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies.) Whichever way that debate turns out, two trends seems clear today: many people without digital skills—or a digital mindset—are suffering job losses, or reduced upward job mobility, and the benefits of this new economy are not being widely shared. “The digital economy,” reported The Economist in 2014, “far from pushing up wages across the board in response to higher productivity, is keeping them flat for the mass of workers while extravagantly rewarding the most talented ones.”

Nor, as is sometimes thought, are jobs in the digital economy replacing the ones being lost in the old economy. Citing sectoral employment statistics, the political scientist Ronald Inglehart wrote this in the January/February 2016 issue of Foreign Affairs:

Some assume that the high-tech sector will produce large numbers of high-paying jobs in the future. But employment in this area does not seem to be increasing; the sector’s share of total employment has been essentially constant since statistics became available about three decades ago. Unlike the transition from an agricultural to an industrial society, in other words, the rise of the knowledge society is not generating a lot of good new jobs.

Beyond this are other factors contributing to the anxieties ordinary people are feeling in the face of digital disruption.

First is the issue of privacy. The four principal digital platforms—Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon—have accrued enormous power by virtue of how much they know about us. But this has profound consequences for us beyond our status as consumers. Apple’s recent refusal to help the FBI crack the San Bernardino shooter’s iPhone (which the Bureau cracked anyway) may have been motivated by good intentions. But surely the company’s sheer size makes this more than merely a corporate decision. Who elected Apple CEO Tim Cook to make decisions between privacy and national security? It is dangerous in a democracy to hand such power to a technocratic elite and for our behaviours—as captured digitally—to become commoditized.

Second, there is no new status quo. Digital technologies are changing so rapidly that many cannot seem to catch their breath before the next innovation is upon us. As one city planner told me, “we can’t even figure out how to regulate Uber and now we have to think about driverless cars and drones?” One lesson of history is that change, if it is to be broadly and deeply accepted—and not provoke a backlash—should proceed slowly. The digital playbook, however, seems to be based on overwhelming, and continuous, change. Echoing the Romantic reaction to the industrial revolution, it is perhaps not surprising that we are living in a period of heightened environmental awareness, or that both the digital revolution and the modern environmental movement began in California.

Third, there is a disconnect between digital leaders’ utopian belief in the transformative power of technology to bring about unambiguously positive change and people’s more realistic view of things. Most people—whether by temperament, belief or experience—can see very clearly that digital technologies offer a mixed bag of consequences. For every iPhone that helps a child stay in touch, there is a parent cursing the device as a distraction from homework.

Finally, I believe there is a growing suspicion among ordinary people that the institutions they interact with on a daily basis—corporations, not-for-profits, government ministries and agencies, schools—have no answers to this disruption, and are as bewildered about where we are headed as they are. If you have children in the public education system, ask yourself: aside from a handful of innovative educators, do you think that the teachers, principals, boards and ministries of education really have any idea how to teach children for the 21st-century digital world?

Caught between the utopian dreams (and much more prosaic reality) of the digital disruptors on the one hand and the rear-guard action of familiar, but faltering, institutions on the other, ordinary individuals fully trust neither. Is it any wonder many people feel stressed out?

Of course, digital technologies are not the only force leaving people feeling vulnerable. Accelerated globalization, climate change, urbanization, terrorism and other forces are having deep impacts on our sense of control over our lives, as well. Yet, given their ubiquity, they are undoubtedly an important factor.

The historian Melvin Kranzberg was the founding editor of Technology and Culture, an influential academic quarterly, and one of the founders of the Society for the History of Technology. In a 1985 address to the society, he outlined what had already begun to be called “Kranzberg’s laws,” which he described as “a series of truisms deriving from a longtime immersion in the study of the development of technology and its interactions with sociocultural change.” (Melvin Kranzberg (1986), “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws.’” Presidential address to the Society for the History of Technology, October 19, 1985.)

All of Kranzberg’s six laws deserve attention, but two strike me as especially relevant here.

Disruptors should heed Kranzberg’s first law: technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral. By that he meant that “technology’s interaction with the social ecology is such that technical developments frequently have environmental, social, and human consequences that go far beyond the immediate purposes of the technical devices and practices themselves, and the same technology can have quite different results when introduced into different contexts or under different circumstances.”

Nuclear power is a good example of this context-dependent value of technology. Nuclear medicine is good. Nuclear warheads, not so much. But Facebook is a good example, too. The social network’s 1.6 billion users attest to its popularity among all age groups. It helps people stay in touch, it reunites long-lost friends, it provides an outlet for shy or house-bound people to communicate and interact with others. But, as C.J. Chivers reported in The New York Times in April, it can also have more nefarious uses: “A terrorist hoping to buy an antiaircraft weapon in recent years needed to look no further than Facebook, which has been hosting sprawling online arms bazaars, offering weapons ranging from handguns and grenades to heavy machine guns and guided missiles.”

Digital entrepreneurs—and their numerous cheerleaders—should remember that the technologies they are developing and marketing, and the speed at which they are doing so, mean that we are less able to digest, understand and plan for the technologies’ consequences—some of which will be unforeseen. If they do not, they should not be surprised of a growing backlash against them. A little modesty would not hurt, either. Nobody likes know-it-alls, especially self-righteous ones.

Kranzberg’s fourth law is wordier: Although technology might be a prime element in many public issues, non-technical factors take precedence in technology-policy decisions. By non-technical he meant political and social forces. Let’s come back to nuclear power. There is a straight line between Japan’s 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear crisis and Germany’s decision to abandon nuclear power—the astonishing decision to replace nearly a quarter of the country’s electricity supply by 2022. That decision was a political one, taken by a government in response to its public’s refusal to accept the potential consequences of a hitherto widely used technology.

The lesson here is for those of us at the centre of the arrow. Ultimately—whether as individual consumers or citizens—these technologies exist for us and it is up to us to determine how—or even whether—we want them in our lives. Do we want driverless cars on our roads? Do we want drones in the skies above our cities? Only by debating the merits of these technologies—by trying to understand what we gain and lose in adopting them—can we decide. In his speech, Kranzberg quotes the historian Lynn White Jr. in saying technology “opens a door, it does not compel one to enter.” That is exactly right and we should all remember our power to affect policy outcomes.

Finally, the disrupted. About a year ago, the CEO of a well-regarded organization asked me what social media platforms do we need to be on. After listening to her describe the challenges she faced in this new digital world, I suggested she was asking the wrong question. The right question to ask was, to my mind, how is your business changing as a result of digital technologies. Unfortunately, too many institutions are asking the wrong question, and merely reacting to digital change, rather than adapting to it. As Christensen suggested, many will probably not survive.

If this were merely a case of business transformation, the results would be difficult, but manageable. But digital disruption is affecting all our institutions, the very entities that provide us with a sense of stability and predictability during periods of change. This is dangerous and suggests a reason populist demagogues are succeeding in a number of European countries and in the United States. Many people really do believe the system is broken.

To counteract that belief, existing institutions must work much harder to prove their worth. They must adapt to the changing environment while still delivering on their purpose—to firmly answer the questions “why are you here” and “who are you here for” while readjusting the way in which they work. Is the purpose of a university to teach students or to have them attend classes in certain buildings, in certain neighbourhoods, in certain cities? I do not know the answer to that question, but I know it must be asked.

I am not a Luddite. I use and enjoy certain digital technologies and appreciate the many ways my life benefits from them. Nor am I a grumpy middle-aged man who is worried that digital technologies are making me redundant (although there are plenty of people who do have those worries). But I am also aware that these technologies come with a cost. And that cost may, at some point, not be a price I am willing to pay.

Where is the arrow of digital disruption pointing? No one really knows. But it is important for us to understand how we can guide its flight into the future.

Dan Dunsky was executive producer of The Agenda with Steve Paikin, from 2006 to 2015, and is the founder of Dunsky Insight.