Over the last year the global refugee crisis has gone from an ongoing and unresolved humanitarian problem to an international political challenge that threatens the stability of Europe, the sustainability of international refugee law and the capacity of United Nations institutions. It is timely to try to situate the mass movement of affected populations in the context of political instability, state insecurity and the resulting oppression and persecution of minorities, rather than be swept along by the heart-rending stories and images, and to consider how the international community can respond to what will inevitably be similar challenges in the future.

As a result of the prolonged conflict in the Middle East, particularly in Syria, but also in Iraq, Turkey and Afghanistan, hundreds of thousands of people have been forced from their homes and many of them have fled their countries, seeking asylum in neighbouring countries or further afield. Although the conflict and resulting population movements have been going on for more than five years, it is only within the last 18 months that residents of developed, western countries have become aware of the dimensions of the situation, the numbers of people affected and the desperate circumstances the refugees find themselves in. Canadians and their government have shown compassion and generosity in recent months in organizing the reception of thousands of Syrian refugees, but the Syrians are only the tip of an iceberg. Around the world, there are millions more refugees, to say nothing of displaced persons trapped in their home countries, who need help and protection. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees says that the numbers globally of people at risk, refugees and displaced persons are at their highest level ever, reaching an estimated 60 million at the end of 2015.

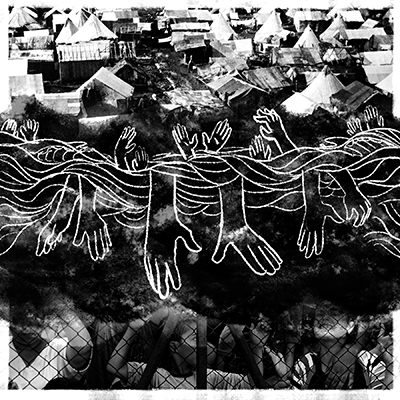

The movement of large numbers of a country’s population from their customary homes and regions is usually a signal that political processes and the rule of law are dysfunctional or have failed altogether. People who become refugees are usually fleeing persecution due to their ethnicity, political affiliation, sexual identity or religious beliefs. Conflict is frequently the trigger of mass population movements that often generate refugees. Leaving one’s home country in search of a job or better economic prospects does not qualify a person as a refugee. The formal definition of who is a refugee is set out in the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, which has been signed and ratified by 147 countries, including Canada. This forms the basis for the framework of international refugee law setting out, inter alia, the rights of refugees and the obligations and responsibilities of countries receiving these people, whether countries of first asylum or of permanent refuge. Refugees, especially children, are among the most vulnerable populations in the world. Already traumatized by the circumstances they are fleeing, they are vulnerable to being preyed upon by smugglers, criminal gangs, and hostile populations in the countries of temporary or first asylum. In some situations they are victimized by the police and other security forces of countries of first asylum that are not willing to meet their responsibilities under international refugee and humanitarian law. Young male refugees, especially from Middle Eastern countries, disenfranchised, marginalized and discriminated against, are particularly susceptible to radicalization and the blandishments of recruiters for extremist groups.

Most people who become refugees want nothing more than to return to their homes to re-establish their lives and livelihoods and find peace and stability. They deserve to be treated with dignity, respect and fairness. In the case of the refugee population fleeing Somalia in the early 1990s, after the collapse of effective government, many now live in what is believed to be the largest refugee camp in the world, at Dadaab in northeast Kenya. Among the more than 800,000 people in this camp are multiple generations of the same families—mother, daughter and granddaughter, existing in a semi-desert environment, totally dependent on external support for food, water and basic social services, and vulnerable to attack from marauding groups of bandits or gender-based violence as they struggle day to day for food, water, access to proper sanitation facilities, firewood and other essentials.

Tyler Kline Longmire

Markazi Camp in Djibouti houses 4,000 of the 19,000 Yemeni refugees in that country. There are an estimated 175,000 Yemeni refugees as the result of the civil war in their home country. Kakuma Camp in northeastern Kenya, near the border with South Sudan, was established in 1991. Among its population of 180,000 are South Sudanese, Sudanese, Somalis, Ethiopians, Burundians, Rwandans, Eritreans, Ugandans and Congolese. The “Lost Boys of Sudan,” who found new lives in the United States, came from Kakuma Camp.

Many refugees are unable or unwilling to live in camps. They try to find accommodation and livelihoods in countries of first asylum, sometimes with relatives, often with little economic and social support. Lebanon is an example where a country with a population of four million is hosting 1.5 million refugees. Not only do the refugees experience hardship but the host country population has to compete for employment opportunities and basic shelter, food and other forms of support.

Of particular concern is the effect on children. There is trauma as the result of being wrenched from the only homes they have ever known, frequently witnessing violence against family members. There is loss of educational opportunities; despite the best efforts of international organizations and civil society groups working in refugee camps, the building, staffing and operating of schools are often not possible due to lack of funds and instability of the camp environment. There is also the impact on children’s health due to insufficient food availability and inappropriate types of food to support growth, both physical and mental. Girl children are especially vulnerable to sexual violence. It is very difficult to imagine the consequences for successive generations of refugees living in camps that have existed for two or three decades, depending almost totally on external support. In the early 1990s, the average length of stay in (supposed) temporary refugee camps, with a much smaller refugee population in the world, was nine years. It is now almost 20 years.

Confronted with the unprecedented numbers of refugees, especially those trying to reach asylum in Europe, mass media have indulged in what can only be described as hysterical pack behaviour. Reporting has invoked the prospect of terrorist “sleepers” within the refugee populations and has played up the opposition of nationalist groups in some countries of refuge to receiving refugee populations, amid claims that the new arrivals will displace citizens from their jobs, increase criminal activity, and generally destabilize and threaten life in the receiving countries. In some countries elected officials have gone to what can only be described as ridiculous lengths to raise barriers to refugee arrivals. In Denmark, in January this year the parliament approved a new law allowing authorities to confiscate from arriving refugees valuables worth more than $2,000, and made it more difficult for asylum seekers seeking to be reunited with their families.

The large number of refugees entering Europe over the last 18 months has provoked fear and resentment and has been used by nationalist politicians to advance their standing by encouraging anti-immigrant sentiment. Although there is support for German chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to admit large numbers of refugees, in recent German state elections anti–immigrant right-wing parties made significant gains. The European Union has negotiated an agreement with Turkey to keep refugees in that country and accept the return of refugees from Greece, where they have been trapped by the closure of land borders to the rest of Europe. This comes close to refoulement—the forced return of refugees to their country of origin—which is prohibited under international law.

In Canada, after an initial period of uncertainty regarding the numbers of refugees the government was willing to authorize, especially from Syria and other conflict-affected countries in the Middle East, there has been a concentrated effort to accept privately sponsored and officially supported refugees from that region, as well as ongoing reception of asylum seekers from other parts of the world. In 2014, Canada accepted 7,573 government-assisted refugees and 4,560 privately sponsored refugees, and 13,500 persons made a refugee claim on arriving in Canada. People accepted for both government and private sponsorship are recognized as refugees through a formal process administered by UNHCR with the logistical support of the International Organization for Migration. The individuals claiming refugee status on arrival are subject to a determination process according to international law and the above-mentioned 1951 UN Convention on the Status of Refugees.

Is Canada doing the right thing? We are a multicultural country of immigrants and we have a proud history of accepting populations at risk, going back to Hungarians in the 1950s, Ugandan Asians in the early 1970s, Vietnamese boat people in the mid 1970s, Somalis in the early 1990s and Kosovars in the late 1990s. Also, many people have come to Canada over the years from the violent, persecution-affected countries of Central America, although these refugees have arrived in much smaller, less visible groups or individually. Canadians understand the moral imperative to provide refuge and support to people forced to flee their homes, although they may not be aware of the obligations of their country under international humanitarian and refugee law. They understand that Canada has the capacity to receive and absorb people at risk. They know it is the right thing to do.

Is Canada doing it right? It would appear that for the refugees able to identify as Syrian, the selection and support system is working as well as could be hoped. The reception of 25,000 Syrian refugees in just over two and a half months—with the intention to double this number by the end of 2016—is a remarkable achievement, and the warmth of the welcome from individual and private group sponsors has been astonishing. Problems in finding appropriate permanent accommodation and some initial logistical glitches should not detract from this accomplishment. For non-Syrian refugees the picture is not as clear, however. It seems that there are now two categories in the Canadian system: Syrian-origin people and others. Special measures are being taken for the first category, such as a waiver from the requirement to repay, during the first year of residence here, the cost of travel from the country of initial refuge to Canada, and accelerated processing through the refugee determination process administered by UNHCR and Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. If these are short-term measures, it is understandable, but it does indicate shortcomings in the Canadian system that have to be fixed. As well as the logistical issues related to accommodation, most refugees need assistance to learn one or the other of the official languages, and many need help to deal with the trauma they have suffered in fleeing their home country and existing in temporary asylum before coming to Canada.

Notable among the other group of refugee candidates are those who claimed asylum on arriving in Canada before the end of 2012, when procedural changes were implemented. There are almost 6,500 people in this category, whose cases are to be decided by the Immigration and Refugee Board. Some of these claimants are in Canada while immediate family members have to stay abroad. They have to obtain work permits in order to seek employment, and many live on the edge of poverty given the insecurity of their situation.

In the broader, global context, Canada has also to consider political and diplomatic actions to protect the refugee populations who will never reach Canadian territory, or other countries of permanent asylum. As part of its examination of Canadian foreign policy, the government must identify actions it can take to reduce instability, state fragility and the abuse of human rights that result in the displacement of populations and creation of refugee movements. Both on its own and with likeminded partners, Canada should work to address the causes of conflict, reinforce the rule of law, and speak out against human rights abuses and act to reduce those abuses. Failure to act will mean that ever greater numbers of people will be displaced from their homes around the world and many of them will become refugees in need of asylum and physical support. It is in Canada’s self-interest, properly understood, to devote as much effort and resources to deal with the causes of refugee movements as it is currently committing to assist the refugees themselves. If Canada becomes a member of the United Nations Security Council, as many hope, is it too much to ask that this be one of our priorities?

As well as pursuing the long-term goal of peace, security and stability to reduce the causes of population displacement and refugees, Canada could in the near-term increase its funding and policy support for multilateral agencies assisting refugees. At the UNHCR program and the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian refugees, as well as at the UN General Assembly, Canada could lead the process for improved norms and legislation to protect refugees, and ensure they are treated with dignity and that their entitlement to asylum is respected. Although this work is far less glitzy than announcements for the media of funds to run camps, feed clothe and house refugees, or mobilize mammoth exercises to bring them to Canada, it is essential to refugees’ ability to gain asylum and eventually return home or establish their lives in a new country.

Hunter McGill is a senior fellow at the University of Ottawa School of International Development and Global Studies. He is also a member of the McLeod Group.