It haunts Israelis still—the image of a 19-year-old Israeli soldier, a medic with the rank of sergeant named Elor Azaria, captured on video executing a wounded Palestinian prisoner who lay inert on the street in the Israeli-occupied West Bank city of Hebron. The Palestinian, Abdel Fattah al-Sharif, was one of two young men who had stabbed and moderately wounded an Israeli soldier near a settlement of extremist Jewish activists, that day in March of 2016. The execution was no act of self-defence. Azaria, who had treated the wounded Israeli soldier, was shown calmly handing his helmet to a colleague, cocking his rifle and taking a few steps toward Sharif, then shooting him in the head. The video, recorded by a volunteer in the Israeli civil rights group B’Tselem, went viral. Azaria was duly convicted of manslaughter in January and sentenced to 18 months in prison.

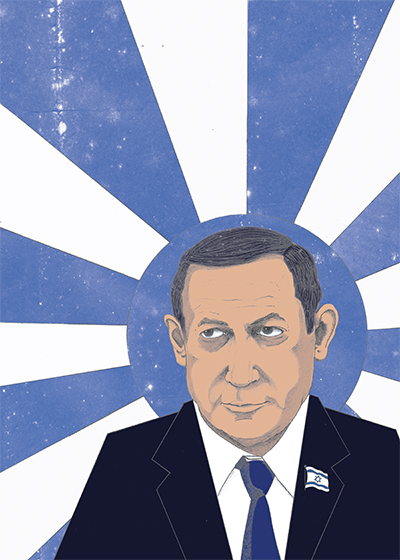

But his trial and the accompanying outcry have illuminated a deep and fundamental divide in Israeli society, one that is exacerbated by U.S. President Donald Trump’s contentious announcement on December 6 recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital. The chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) quickly denounced the soldier’s action, as did then-defence minister Moshe Ya’alon, who described it as an “utter breach of IDF values and of our code of ethics in combat.” Even Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, in the early hours following the incident, described Azaria’s behaviour as unacceptable. In the days that followed, however, there was an outpouring of public sympathy for the young Israeli: This was a Palestinian terrorist, many said; the sergeant should get a medal. To others, the Israeli soldier was at the very least an innocent, like so many of their own boys conscripted into the army.

The Azaria sympathizers were encouraged by former foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman, himself an Israeli settler in the disputed West Bank, and leader of the secular right-wing party Yisrael Beiteinu (which translates to Israel Our Home), who took pains to sit beside the soldier in the early days of court proceedings. A public opinion survey soon found that 68 percent of Israelis supported the shooting and a majority of them said the soldier should not face prosecution. It wasn’t long before Netanyahu qualified his earlier condemnation and announced he had telephoned the soldier’s parents to convey his sympathy. The prime minister and his defence minister battled openly over the case, and the tensions culminated in Ya’alon’s forced resignation and Lieberman’s appointment as defence minister.

After my many years covering the Middle East, and Israel in particular, I can say that even more than the poll results, the fact that Ya’alon, a former IDF chief of staff, should be treated this way is an indication of how much Israel has changed. “It didn’t matter that he had an impressive military record, opposed the peace process, or supported settlement expansion,” Haaretz editor Aluf Benn wrote in the U.S. journal Foreign Affairs. “In Netanyahu’s Israel, merely insisting on due process for a well-documented crime is now enough to win you the enmity of the new elite and its backers.”

Saman Sarheng

Nor is Ya’alon the only one. Israeli President Reuven Rivlin, a respected conservative from the governing Likud party, also found himself on the other side of the divide from his party’s leader. The president, who is elected by a vote of the Israeli Knesset, had made clear his views a few months before the Azaria killing when young settler extremists stood accused of firebombing a Palestinian home in the West Bank in the middle of the night, killing a mother, father, and their 18-month-old child. Israel, he said at that time, must not tolerate the targeting of those who are not Jews: “We must deal with terrorism as terrorism, whether it’s Arab terror or Jewish terror.” The Azaria case still dominates headlines today in Israel, almost a year after the verdict, and in late November, President Rivlin formally denied a request, signed by Prime Minister Netanyahu himself, that he pardon Azaria. Instead, the president added his voice to those denouncing the summary execution. For this, he has incurred the wrath of the prime minister’s cronies, who have publicly portrayed their head of state as a traitor.

The episode is just the thin edge of the political wedge. In a controversial speech to the Israeli Bar Association in August, Israel’s justice minister, Ayelet Shaked, rebuked the country’s Supreme Court for giving insufficient weight to Zionism and the country’s Jewish majority when rendering its decisions. “Zionism should not continue, and I say here, it will not continue to bow down to the system of individual rights interpreted in a universal way that divorces them from the history of the Knesset and the history of legislation that we all know,” she said. A so-called “nation-state” bill now being advanced by the government, Shaked vowed, will be a “moral and political revolution,” putting civil rights in their place.

Indeed, the political rift within the Jewish state goes to the heart of some fundamental questions: Do civil liberties apply equally to all citizens? What are the rights of an Arab in the occupied West Bank? Would the Jewish majority in Israel be content to take away those rights and liberties from non-Jews in Israel and the occupied territories? The apparently affirmative answer to that last question suggests that the Jewish majority no longer believes the land that lies between the Mediterranean and the Jordan River can support both the Israeli and Palestinian peoples.

To President Rivlin and to many others, this moral and political revolution betrays the real Zionist ethos. Theodor Herzl, who fathered modern Zionism in the late 19th century, held that a Jewish state would not only safeguard Jews fleeing persecution in Europe but would be a model of civil and political rights. Herzl’s vision, set out in his 1896 booklet, Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) and his 1902 novel, Altneuland (Old New Land) was of a promised land that would be shared with local Arabs—which was not surprising, since about 90 percent of the population of Palestine at that time was Arab. He foresaw a democracy in which Jews and non-Jews voted, where women were fully emancipated, and there was clear division between religion and state. Judaism and all religions, Herzl liked to say, would be kept in their places of worship just as the military would be kept in its barracks. In this idyllic world, there was little friction between Arab and Jew; Arabs held some of the highest offices in the land.

This was also the vision of Zionism endorsed by the predominantly secular Zionist Organization (now the World Zionist Organization) in its numerous congresses, and it was the movement endorsed by Britain in the Balfour Declaration, the 100th anniversary of which was marked in November.

It was not without its tensions. On that cloudy day in London a century ago, Chaim Weizmann, the unofficial but effective leader of the worldwide Zionist movement, waited nervously outside the British cabinet office while the ministers of David Lloyd George’s government debated the merits of recognizing a claim by “the Jewish people” to a homeland in Palestine, which, in the midst of the First World War, still was part of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, Mark Sykes, a Middle East advisor to the government, emerged holding a document. “Dr. Weizmann, it’s a boy!” he exclaimed, apparently assuming that the declaration he carried, signed by British foreign minister Arthur Balfour, would please the Zionist leader.

But Weizmann, an eminent scientist, could not hide his disappointment. In his memoir, Trial and Error, he wrote: “I did not like the boy at first. He was not the one I expected.” The sticking points were in this passage: “His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine…”

Weizmann was disappointed that the Jewish national home would be “in Palestine,” rather than be all of Palestine. For another, he didn’t like the acknowledgement of “existing non-Jewish communities” in what he hoped would be the Jewish homeland. True, this was the first official international recognition of the Zionist claim to any national home in Palestine, and for this Weizmann and others were grateful. But Weizmann worried that the recognition of another people in Palestine, whose rights needed to be safeguarded from the Zionist enterprise, would create problems down the road. As indeed it did, before long.

Nevertheless, that was the view of Zionism embedded in the mandate of Palestine administered by Britain following the First World War and which was practised by the thousands of mostly young, secular pioneers who worked the land and toiled in the cities that sprang up. The dual nature of this Palestine was the basis of the 1947 UN partition plan that laid out the contours of an Arab state and a Jewish state (as well as an international trusteeship to safeguard Jerusalem and its holy sites). Most importantly, it is the view embraced in Israel’s 1948 Declaration of Independence: “The state of Israel will promote the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants…[and] will uphold the full social and political equality of all its citizens without distinction of race, creed or sex.” It specifically assures “the Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel” that they will enjoy “full and equal citizenship and due representation in all its bodies and institutions, provisional or permanent.”

Such democratic values are, today, in retreat. The Jewish nation-state law, now being voted on in the Knesset, will have citizens pledge allegiance to the “Jewish state of Israel.” It will remove Arabic as an official language—reducing it to a language with “special status”—and, overall, give Jewish interests priority over individual rights. Shaked, the justice minister, champions this controversial law, which places Jewish community interests over all others. The law also has the resounding support of the right-wing and religious parties that make up the governing coalition.

Shaked, a secular Jew whom many see as a future national leader, made her worldview known several months ago in an essay for the U.S.-based journal of Jewish ideas, Hashiloach:

It is the natural right of the Jewish people to live like every other nation. A Jewish state is a state whose history is combined and interwoven with the history of the Jewish people, whose language is Hebrew and whose main holidays reflect its national revival. A Jewish state is a state for which the settlement of Jews in its fields, cities, and towns is a primary concern. A Jewish state is a state that nurtures Jewish culture, Jewish education, and the love of the Jewish people. A Jewish state is the realization of generations of aspirations for Jewish redemption. A Jewish state is a state whose values are drawn from its religious tradition, with the Bible the most basic of its books and the prophets of Israel its moral foundation. A Jewish state is a state in which Jewish law plays an important role. A Jewish state is a state for which the values of the Torah of Israel, the values of Jewish tradition and the values of Jewish law are among its basic values.

This is a new definition of the State of Israel. “Shaked’s concept of Jewish ethnic superiority rests not only on a closely held ideology, but on the politics of fear,” Daniel Blatman, a historian at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, wrote in an article for the Haaretz newspaper. That political current is in line with a xenophobic conservatism on the rise in a number of western countries, but in his article, Blatman, who is head of the Institute of Contemporary Jewry at the university, identifies a more troubling parallel: the American South of the 1930s:

Instead of white supremacy, we will get Jewish supremacy, together with an ethnocentric-racist vision that will allow for some vital economic practicalities. After all, Shaked’s Jewish state doesn’t want to separate from the Palestinians, and certainly doesn’t want to make them citizens. Just as in the American South the segregation and political discrimination against blacks created a brutal, racist social and political order, so will Shaked’s new national-Zionist state, which won’t be prepared to bow its head before universal definitions of individual rights.

Moderates in Israel are concerned that the Jewish state, having inoculated itself against such universal values, will continue to oppress minorities as well as those who disagree with the state’s new ideology. Already, Education Minister Naftali Bennett, leader of the Jewish Home party, has introduced an academic code of ethics for post-secondary institutions that will prevent faculty from voicing political opinions in the classroom or even on campus. Academics are outraged at what they see as a restriction on freedom of speech.

But what is at stake is not only free speech. An amendment this year to Israel’s entry law allows authorities to deny a visa to anyone who advocates for boycotts, divestment, or sanctions against Israel. (BDS, as the movement is known, is a pressure tactic used in support of Palestinians in an effort to persuade Israel to end the occupation of the West Bank and the border restrictions placed on Gaza.) In November, the new law was used to bar entry to members of a delegation of European parliamentarians and French mayors because they had called for a boycott of Israel. And it has even allowed the government to turn away Jews who are members of an advocacy group known as Jewish Voice for Peace.

Israel’s national religious right has welcomed the changes, seeing them as Shaked asserting priority for the Jewish community. “These things are so vital today, they have to be at the centre of our educational work, and certainly in law,” said Rabbi Haim Druckman, head of a network of Orthodox religious schools and a founder of Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful), a vanguard settlement movement. “We must place the needs of the community at the top of our priorities—the people of Israel, the Land of Israel—and not the needs of the individual, as much as they are important…The needs of the community take precedence.”

In this new Israel, which is beginning to sound a little like an Islamic republic, it is not only non-Jews who are finding their rights at risk, but also Jews who are not considered Jewish enough. When it comes to religious authority it is the Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, leaders who determine such things as who is a Jew and the place of women in Jewish practices in Israel. The Chief Rabbinate, made up mostly of Haredi chief rabbis in several jurisdictions in Israel, frequently rule that people who convert to Judaism as Reform or Conservative Jews (the majority in North America) are not recognized as real Jews and therefore not entitled to claim Israeli citizenship or partake in religious (Orthodox) activity.

This has been the case since the state was established, but the number of decrees and the public backlash against them have increased in recent years and spilled over into public holy sites, particularly the Western Wall. Known as the Kotel, this towering wall of enormous Herodian cut-stone blocks is the last portion of the ancient Jewish temple in the Old City of Jerusalem still standing, and a favourite site for prayer by Jews of all persuasions. Access to the wall, however, is controlled by the Haredim. Accordingly, there is a large area designated for men, and a smaller adjacent area for women, separated by a screen. However, women, even in their own space, are not permitted to wear prayer shawls or other religious garb, nor to hold Torah scrolls. Nor are female rabbis permitted to conduct services. Failure to abide by these rules can bring down the wrath of the ruling Haredi leadership, who frequently dispatch gangs of Orthodox youths to intimidate the offending female worshippers, who mostly are members of the Reform or Conservative movements.

In January, Israel’s Supreme Court ruled that women could pray as they wish. The trouble is, the Haredi authorities do not accept this ruling. So a kind of compromise has been worked out so that, at sunrise at the start of each Jewish month, a group of women, known as Women of the Wall, pray in the women’s section and proudly hold the Torah. Dozens of Haredi youths still turn out to oppose the “infidels,” but the women are protected by a great number of Border Police officers positioned between the women and the hostile Haredi men. As a long-term solution, this arrangement is untenable.

At the same time, Reform and Conservative Jews, who wish to be able to pray at the wall as married couples or families, have sought the help of the government and the courts. Three years ago, Prime Minister Netanyahu asked Natan Sharansky, the one-time Soviet dissident, now chairman of the Jewish Agency, to negotiate a suitable arrangement that would be acceptable to both the Reform and Conservative organizations and to the government of Israel. The result, approved in January 2016, was a plan to build a plaza in front of a part of the wall that extends south of the main section. In this area, separated from the traditional prayer area by a stairway to the Temple Mount and al-Aqsa Mosque, mixed prayer would be permitted. It was a second-class arrangement, but the Reform and Conservative communities were pleased at this significant concession.

The problem, however, is that the government did not speak for the Haredi authorities, who continue to insist that mixed prayer is forbidden and that if the government gives official approval to these apostates, as they see the non-Orthodox communities, the Haredi parties within the coalition will bring down the government. Flexing their muscles, the Haredim this past spring dispatched members of a settler yeshiva (religious school) to occupy the area designated for future egalitarian prayer. The pressure tactics worked—in June, Netanyahu announced that the plan for a mixed prayer area was on indefinite hold.

Ironically, all this intensification of Orthodoxy is being done in the name of “religious Zionism.” Yet, for decades, the Haredim wanted no part of Zionism and certainly no part of a secular state of Israel they considered sacrilegious—a Jewish state, they said, must wait for the coming of the Messiah. That has gradually changed since Israel was born. While the Haredim reject modern culture and want little to do with the state, their numbers are growing greatly, as is their political influence. Today, about 17 percent of Israel’s Jewish population is ultra-Orthodox, as are 29 percent of Jews under the age of 20. As it grows, this community is determined to make Israel properly Jewish, as they see it. According to the Pew Research Center, some 86 percent of the Haredim want Israel to be a state governed by Halacha, Jewish law—a theocracy rather than a democracy.

The work of overturning the secular state began in the early days of the young country, starting in 1950, and one of the guiding lights who ushered in the theocratic political currents that hold so much sway today emerged during this period. The late Mordechai Eliyahu, Sephardi chief rabbi of Israel from 1983 to 1993, was one of five yeshiva students who founded a terrorist group known as Brit HaKanaim (Covenant of the Zealots). The group, which grew to two or three dozen, firebombed cars that were driven on the Sabbath and butcher shops that sold pork, all for the sake of establishing, according to their manifesto, “an Orthodox regime, based on the principle of God’s justice, a dictatorial regime with no democracy.” The zealots met their downfall, however, in an attempt to smuggle a bomb into the Knesset on the day when the members of the Israeli parliament were debating a proposed law to conscript women into the military. Eliyahu and three others were sentenced to prison terms of between six and twelve months.

Years later, in 1998, Rabbi Eliyahu told me in an interview that his views of a theocracy had not changed, only the means of achieving it. However, he continued to support others who used violence to bring about a purely Jewish state. He was a friend and spiritual advisor to Meir Kahane, a radical rabbi who founded the Jewish Defense League in North America and the anti-Arab Kach (Thus) party in Israel. Kahane was assassinated in New York in 1990 and, at his funeral in Jerusalem, it was Eliyahu, then Sephardi chief rabbi of Israel, who delivered a eulogy. Kahane had cherished his relationship with Eliyahu, and had said that Rabbi Eliyahu gave him “religious legitimacy.”

Through the past three decades the dream of a Jewish kingdom as well as violent means of trying to drive out the Arabs have been kept alive by far-right Kahanists. Baruch Goldstein, the Israeli military doctor who used the Jewish holy day of Purim to kill 29 Palestinians at prayer in the Sanctuary of Abraham (also known as the Cave of the Patriarchs) in Hebron in 1994, was a Kahane disciple. As was Yigal Amir, who assassinated prime minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995. For years after, Eliyahu joined with other, mostly settler, rabbis in seeking amnesty for Amir.

The most extreme example today of such violence is carried out by a group of settler youths led by Rabbi Kahane’s grandson, Meir Ettinger. They call themselves the Revolt, the title of Menachem Begin’s memoirs about the pre-state terror group, the Irgun, of which Ettinger’s great-grandfather had been a member. Members of the Revolt today are believed responsible for that fatal 2015 firebombing of a Palestinian family. Outside their home in the West Bank village of Duma the attackers spray-painted the words “Long live the Messiah King” in Hebrew, a slogan of those seeking theocratic rule.

These Jewish terrorists were all ultra-religious extremists and treated that way by the authorities. But their dream of a theocratic state is shared by a growing number of more mainstream Israelis and by well-positioned elements within the Netanyahu government.

For his part, Rabbi Eliyahu, following his time as chief rabbi, became the spiritual mentor of the National Religious Party, known as Mafdal in Hebrew. It was he more than anyone who guided the once-moderate religious party into linking with elements of the Haredim to promote settlement construction and the permanent occupation of the West Bank, or Judea and Samaria—integral parts of the historic Land of Israel. This Har-dal movement, as it is known, was responsible for the construction of the two largest West Bank settlements, Beitar Illit and Modi’in Illit, both completely ultra-Orthodox. Its dream of a theocracy lives on in the Jewish Home party, the home of Bennett, the education minister.

Remarkably, Theodor Herzl foresaw a movement such as the Jewish Home more than a century ago. In his novel, Altneuland, an anti-Arab party took shape and ran for election on a platform of driving out the “outsiders.” The radical group was defeated in the polls and the disgraced leader left the country. Not so in today’s Israel—the xenophobes are winning and Zionism’s dream of democracy is taking a back seat. “We didn’t come here to establish a democratic state,” says Benny Katzover, a longtime leader of the settlement movement in Judea and Samaria. “We came here to return the Jewish people to their land.” Trump’s announcement recognizing Jerusalem as Israel’s capital will only serve to strengthen both the country’s settler movement and the religious extremists who seek a theocracy over all the ancient Land of Israel.

Correction: The original version of this essay mistakenly attributed a statement about “secular U.S. Jews who… lived comfortable lives and didn’t understand the fears of Israelis” to Israel’s justice minister, Ayelet Shaked. The statement was in fact made by Tzipi Hotovely, the deputy minister of foreign affairs. The LRC regrets the error.

Patrick Martin is a former Middle East correspondent for the Globe and Mail.