I will never forget the girl who was both allergic to DEET and highly reactive to mosquito bites. It was her first year tree planting and my second. Every night her eyes swelled shut, and every morning she tucked dryer sheets into her shirt collar and spritzed herself with mouthwash in the hope of mitigating another attack. That didn’t work. Nothing worked. “It won’t be this bad next year,” we’d tell her. “Your rookie skin just isn’t seasoned to the mosquito’s bite.”

My hatred for mosquitoes had never been so virulent as when I tree planted. And then I read Timothy C. Winegard’s The Mosquito. These tenacious creatures that announce the Canadian summer and represent the only reason anyone might actually welcome the season’s end are our deadliest predator. They don’t just bug, they obliterate: 52 billion people since the beginning of time. That’s nearly half of those who have ever walked the planet. Our six-legged foe can drink three times her weight in blood and, a few days later, lay 200 eggs on the slightest pooling of water. She’ll keep up this cycle for the next few weeks of her short life.

Over 7,000 years ago, in central Africa, early agriculture stirred up mosquitoes that had previously kept to themselves. Infected with malaria, which they got from birds, the mosquitoes started to stalk our early ancestors, who developed sickle cell anemia in response. Sickle cell, which creates abnormally shaped red blood cells that prevent the malarial parasite from latching on, can drastically shorten a person’s lifespan. But 90 percent immunity to malaria was, evolutionarily speaking, the better option.

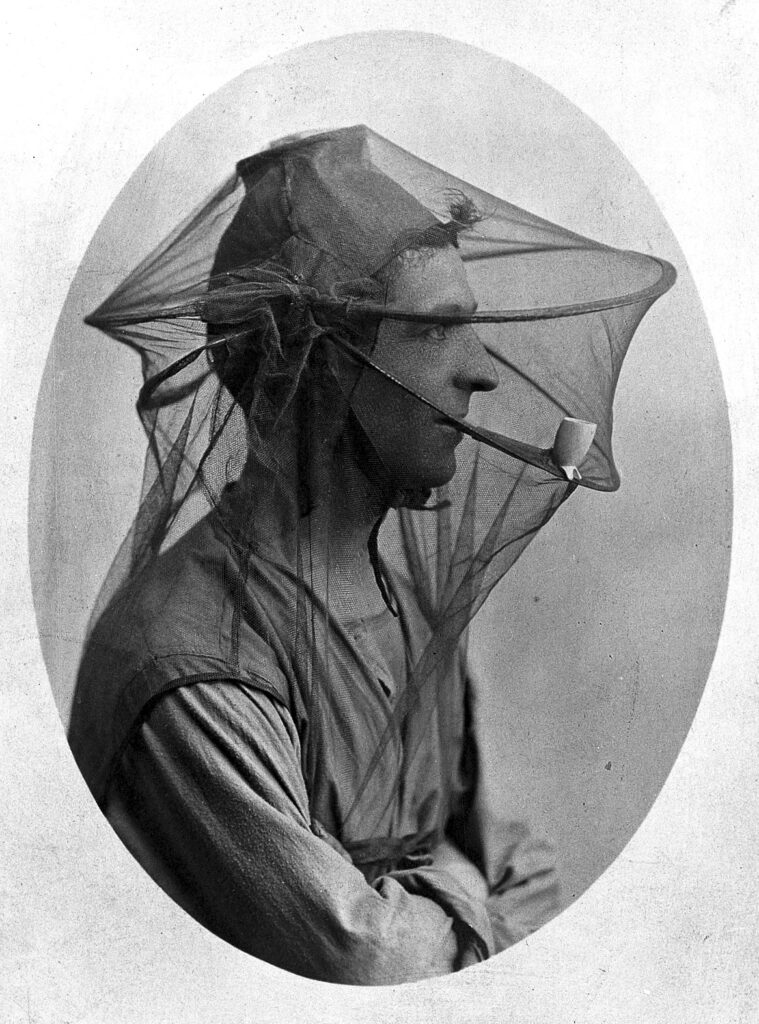

For thousands of years, we have tried — in many ways — to outwit mosquitoes.

Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons

The oldest fossilized mosquitoes have been found in Canada and Myanmar, dating to between 80 and 100 million years ago. (They haven’t changed much when it comes to looks.) Humans, who came to farm Mesopotamia quite a bit after this, first recorded malaria symptoms on tablets around 3200 BCE. And it was Hippocrates who described the feverish, sickly period in summer and early fall — when malaria gripped the population as predictably as Sirius the Dog Star appeared in the nighttime sky — as the “dog days of summer.”

On occasion, mosquitoes have been allies — especially Rome’s. Time and again, they stood guard in the Pontine Marshes surrounding the city, fending off or attacking any army that laid siege. In 451 BCE, they helped repel Attila the Hun. In 390 BCE, when the Gauls finally took Rome, the victors were so sick that they took some gold and limped away. During the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca set eyes on the Eternal City. “There was, however, another unforeseen guardian of Rome waiting in the wings,” Winegard writes. “The mosquito was drafted into service and thrust into action.” In defence of Rome, the mosquito helped save Greco-Roman culture, but then plagued the city with chronic malarial infections that had no small part in the empire’s eventual collapse.

Winegard anthropomorphizes the female mosquito (she’s the one who bites) as an unmatched military general whose capricious allegiances have determined the course of wars. She has helped to draw and redraw lines on the map. And then she’s turned around and decimated the conquering heroes. The military analogy is an apt one for Winegard, who served in both the British and Canadian forces. Now a professor of history and political science at Colorado Mesa University, in Grand Junction, he has published four books on military history. With the deeply researched Mosquito (its bibliography is seventeen pages long), he uses the bellicose insect to tie together a fascinating, sprawling history — from dinosaurs to the banned insecticide DDT.

Beyond geopolitics, and along with the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, mosquitoes poked their proboscis into early Christianity. In the third century, even while Christians were brutally and creatively tortured, the absolute devastation wreaked by malaria and plagues provided a convincing argument for conversion: Jesus heals. Just as Jesus had done, Christians were expected to show compassion for the victims of diseases, which hadn’t yet been attributed to mosquitoes. “After a rocky and violent start,” Winegard writes, “Christianity soon found a home in the minds and ministries of populations across Europe and the Near East as a remedial religion, permanently realigning the balance of power around our planet.”

Indeed, mosquitoes were a catalyst in a shrinking world. They were, Winegard asserts, among the most significant participants in the Columbian Exchange of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. And while they travelled in both directions across the Atlantic, their reign of terror in the Americas was especially pronounced. They decimated the local populations with avian diseases from Africa (as well as a host of other infections, including smallpox), paving the way for European colonization. The loss of native residents also helped perpetuate the use of African slaves — whose hereditary immunities shielded them from many mosquito-borne infections. “African slavery was a central element of the Columbian Exchange and the prosperity of a plantation economy,” Winegard explains. “As the captive indigenous labor force was destroyed by infection, African slaves, and their complimentary free-of-charge diseases, were shipped directly to any destination in the Americas, or globally for that matter.” Powered by slaves, plantations arose around tobacco and coffee — two products inextricably linked to mosquitoes. Puffs of tobacco smoke could help ward off bites, while coffee had a reputation as a malarial elixir.

For centuries, European powers would fight to control the Americas. By 1759, malaria had so depleted France’s Caribbean forces that reinforcements were needed. So the garrison in Quebec sent soldiers to the “mosquito-stoked furnace of the tropics,” and the British saw an opportunity. Major General James Wolfe led the charge on the Plains of Abraham, winning handily. Canada was now British, thanks in part to the little flies.

Perversely, while mosquitoes have been our greatest killers, we have also been their greatest ally. For centuries, we were all too accommodating in transporting them and the diseases they carry. While people around the world fell victim to new strains of infections introduced from elsewhere, mosquito émigrés keenly adapted. And whenever we have developed effective defences — DDT may have done a number on the environment, but it helped reduce mosquito-borne diseases around the world by 90 percent between 1930 and 1970 — mosquitoes have developed immunities of their own. Still, we have had successes.

Mosquitoes and their yellow fever were eradicated entirely from Cuba in 1902, thanks to a 300‑man team that drained swamps and standing water, hung nets, cleared hospitable vegetation, and spread sulphur and kerosene. Using similar tactics, and prescribing workers a preventive daily dose of quinine, the United States finally completed the Panama Canal, a project that had flummoxed the British, had eluded the French (they got about 40 percent through before losing 85 percent of their men), and had killed off 40,000 Spanish workers. This was well after the Darien scheme, a disastrously expensive Scottish attempt to build an overland route across the isthmus that failed so miserably it led to the Kingdom of Scotland’s eventual union with England. By the time the Panama Canal finally opened, just before the outbreak of the First World War, 60,000 had died — but less than 10 percent of these in the final decade of construction. The tide had begun to turn on the mosquito.

In the 1930s, a shirtless and shovel-bearing Benito Mussolini widely promoted his anti-malaria program of clearing brush, planting trees, and draining water to reclaim swampland — including those Pontine Marshes that had long defended Rome. He was actually quite successful: malaria rates dropped by 99.8 percent between 1932 and 1939. Then Hitler reflooded the marshes in 1943, turning mosquitoes against the Allied forces, which suffered a spike of malarial infections.

During war or peace, the mosquito can make herself at home just about anywhere. In Lenin’s Soviet Union, two strains of malaria ripped through the country, reaching as far north as the Arctic Circle in the early 1920s. It was “the perfect storm of temperature, trade, civil strife, suitable mosquitoes, and a vectoring warm-blooded human population,” Winegard explains. In the Canadian Arctic, Nunavut’s only inland community, Baker Lake, carries the unfortunate title of territorial mosquito capital, but the local pests don’t carry viruses like their southern counterparts. That’s changing, as virus-bearing mosquitoes are heading north in greater numbers. Indeed, according to the United Nations, an increase in tick- and mosquito-borne diseases among northern communities is a sure indicator of climate change.

Though mosquitoes quickly reinvent themselves alongside scientific advances and environmental change, we’re still trying to stave off their impacts. Bill and Melinda Gates have contributed more than anyone to modern efforts, investing millions in malaria vaccines and eradication. Still, global attention to malaria is paltry compared with the focus on cancer and HIV/AIDS. “Malaria and other ‘neglected diseases’ are rarities in the affluent world,” Winegard writes, “so they stealthily fly under the R&D radar”— with the mosquito providing the wings.

Earlier this year I was travelling in South America, armed with bug spray and knowing a malarial antidote was just a pharmacy away, when I met an American cyclist who had pedalled from California through Mexico and Central America. Somewhere around Cartagena, he was struck down with fever and arthritic pain and couldn’t possibly pedal any further. Doctors said a mosquito had infected him with chikungunya virus, a relatively new addition to the mosquito’s repertoire, like Zika or West Nile. He would rest and hydrate and eventually continue his journey by bus. “It’s a poor man’s disease,” he told me, “so we don’t really know much about it.” Just the way the mosquito likes it.

Elaine Anselmi is a freelance journalist. Mosquitoes have bitten her in every province and territory, except PEI.