Books about Canadian prime ministers — either as individuals or as a group — have long been a staple of the political and historical literary scene. Last year, when the forty-third general election was still a year away, two such works appeared. One, Power, Prime Ministers and the Press, by the former Maclean’s editor Robert Lewis, described the evolving relationship between the Parliamentary Press Gallery and the prime ministers it covers. It was well received, including a strong review in this magazine. The other, if I may be so immodest, was my own: Being Prime Minister takes readers behind the scenes to see what the office and those who have occupied it are really like. Both titles have found an avid readership.

It’s likely those who enjoy books about our leaders are also aware of two from decades ago, by the eminent historians Michael Bliss, Jack Granatstein, and Norman Hillmer. Bliss published Right Honourable Men: The Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Mulroney in 1994, and Granatstein and Hillmer delivered Prime Ministers: Ranking Canada’s Leaders just a few years later. All of these works were serious undertakings. With polished prose and keen insight, they are important and accessible scholarship.

Unfortunately, Jerry S. Grafstein’s A Leader Must Be a Leader: Encounters with Eleven Prime Ministers is not such a book. From the banal title to the meandering, mistake-filled prose, it comes across as little more than a vanity project by an Ottawa insider who thought he would sit down and bang away at his computer because he had a few stories to tell about the PMs he knew. The book includes no fewer than thirty-nine pictures of the former senator with various prime ministers and other VIPs (Pierre Trudeau appointed Grafstein to the Red Chamber, representing Ontario, in 1984), and the cover doesn’t let you forget the author is “the Hon. Jerry S. Grafstein QC.” Yes, these are important honorifics. But it’s worth noting that even A Great Game: The Forgotten Leafs and the Rise of Professional Hockey, from 2013, identified the author as simply Stephen J. Harper. He was prime minister at the time.

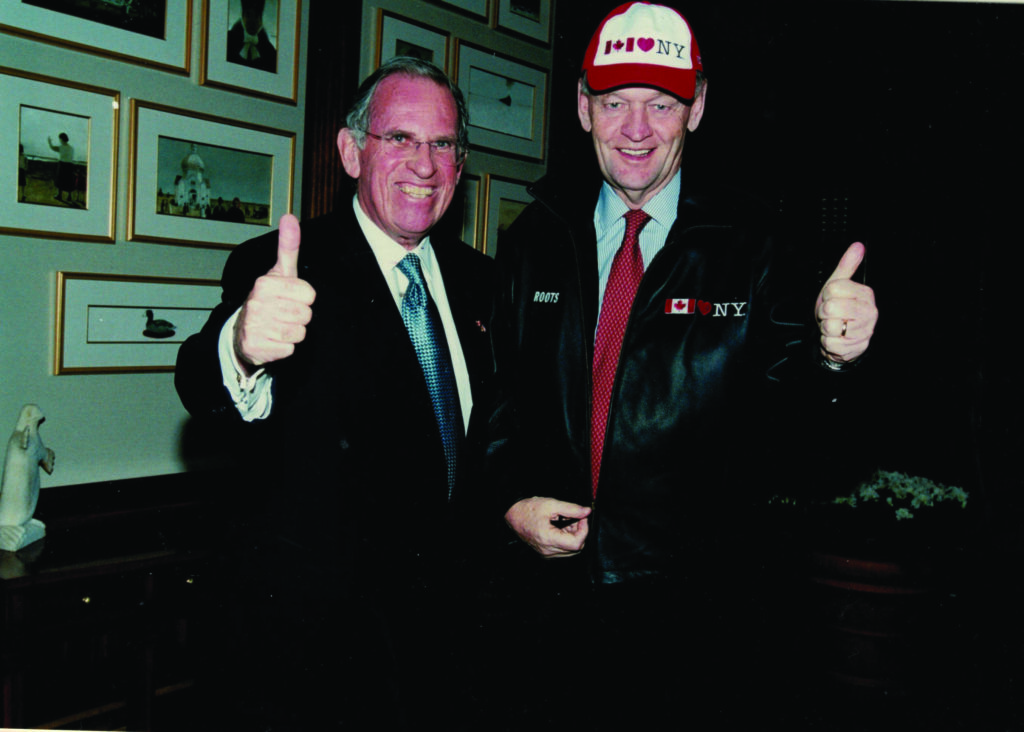

Former senator Jerry S. Grafstein (left) shares a few stories about Jean Chrétien and other PMs he knew.

Mosaic Press

One could probably excuse the overuse of pictures, simple evidence of the author’s proud career in public service and twenty-six years in the Senate. But the hundreds of pages of text around the photographs of PMs are filled with errors of both style and substance, so much so that it leads one to wonder where the chain of command was when the manuscript made its way through the publishing process.

What kind of errors?

Consider: Grafstein writes that John Diefenbaker was born in “Neustadt, a small town in Saskatchewan in 1895.” In fact, Neustadt is in Ontario, 170 kilometres northwest of Toronto. He talks about Lester B. Pearson coming to power in 1962, when it was actually 1963. He recalls Diefenbaker’s landslide election victory in 1957, when he won the biggest parliamentary majority in history. Except it was actually 1958. He spells Sir John A. Macdonald’s name incorrectly, two different ways. He mentions the famous incident when Joe Clark lost his luggage on a trip to the Middle East as prime minister. But it was actually on a trip that Clark took as the opposition leader. Grafstein also explains that Brian Mulroney needed a “showstopper” after the failures of Meech Lake and Charlottetown, and that he found it in a free trade agreement with the United States. The thing is, Meech Lake failed in 1990, and the referendum on the Charlottetown Accord was in 1992. Mulroney and Ronald Reagan signed their free trade agreement in 1989.

This is not an exhaustive list. A Leader Must Be a Leader is riddled with variant spellings of names and other inconsistencies. Some figures are introduced with only last names, for example, while others get their full names. Justin Trudeau is referred to as “Justin” more times than not (and “Justine” in one sentence). It’s often unclear when certain events occurred. We read about the leadership convention that took Joe Clark to the head of the Progressive Conservatives, but without reference to the year it happened. Yes, the context makes it clear that Grafstein is recalling the 1976 convention, but he doesn’t actually say so.

But perhaps the most baffling of all is that Grafstein inexplicably quotes Osama bin Laden on leadership, right next to David Hume and Pierre Trudeau. How does that happen?

This all raises the important point about what needs to go into a book, so that it is polished, accurate, and worth a read. It is clear Grafstein’s pages did not have an editor. It would have been an immeasurably stronger work had it gone through a more rigorous process to give it shape, and to weed out misspellings, missing dates, and repetitions (at one point, “Mulroney” appears eight times in a single paragraph). As most writers know, the editor of your manuscript is one of your best friends.

Authors and publishers have an obligation to take any writing endeavour seriously, perhaps even more so in the area of non-fiction. For writers, the duty is to work hard, get the facts right, look things up when uncertain, read, revise, and reflect on one’s goals for the text. Publishers need to support their writers — and pay respect to their readers — with capable editors. Anything less than this can lead to failure. The underlying implication: we can play fast and loose with the facts. But when the genre is political memoir, the consequences are significant in terms of credibility and national memory.

Is there anything to be gained or learned about prime ministers from this book, one might ask? After all, Grafstein was both a senator and a party operative, with a unique perspective on federal politics. While he peppers his work with anecdotes about the politicians he knew, he doesn’t offer much that’s new about them as individual personalities. He does, however, shed light on the importance of little-discussed aspects of being prime minister, including the relationship with caucus and the party: “Mastery of the Caucus, on issues large and small, achieving and retaining the confidence of the Caucus, is the defining yet little-known ingredient of political success and longevity.”

Grafstein notes how a PM’s leadership qualities can be put to the test during these weekly meetings of MPs and senators. “It is ‘confidence’ that unites a party and makes it powerful within and without,” he writes. “Less is known about the traditions and practices of party caucus than any other aspect of political governance.” To lose one’s caucus, Grafstein shows in ways others have not, is to be in big trouble:

The nature and custom of caucus other than sporadic and distorted leaks, is not studied in courses in schools, little discussed by experts, rarely considered in law schools. . . . Nor does the public understand the fragility of our system of governance that all hinges on confidence in caucus behind closed doors and open votes of confidence in legislatures.

Grafstein offers something worthwhile here, and his thoughts on the inner workings of a political campaign are also insightful. But, alas, these small nuggets are not enough to compensate for a book that had excellent intentions but very poor execution.

J.D.M. Stewart is the author of Being Prime Minister. He lives in Toronto, where he’s writing a new history of Canadian prime ministers.