I’m sixty-five years old. For about sixty of them, I’ve been an airplane geek. I’m not as hard-core as some, but I’m geek enough to know the difference between a turbojet and a turbofan, a Beaver and an Otter. But recently I heard a story I’d never heard before.

It took place on a late winter day in 1908, when a rickety flying machine lifted off a frozen lake near Hammondsport, New York, and a cluster of curiosity seekers looked on. At the controls was a twenty-five-year-old named Frederick Walker Baldwin — nicknamed Casey, after a popular baseball song. The machine flew for ninety-seven metres before a tail strut buckled, abruptly forcing it down onto the ice. Baldwin was unhurt.

Ring a bell? Probably not. Yet, by rights, that ninety-seven-metre stretch ranks as one of the most significant in the history of aviation. Baldwin’s short turn over Keuka Lake was the first public flight of a powered heavier-than-air machine in the United States. Even at less than the length of a football field, it was, at the time, the longest first flight of any heavier-than-air machine — period. Moreover, by stepping into the cockpit at the last moment, because the intended pilot was unavailable, Baldwin became the first Canadian to fly a powered aircraft.

I always thought the first Canadian to fly was Douglas McCurdy. As a kid, I even had a plastic coin from a package of Jell‑O to prove it. The coin replicated the iconic photograph of McCurdy’s flying machine, the Silver Dart, labouring into the winter sky above Nova Scotia’s Bras d’Or Lake, in 1909. It’s true that McCurdy’s feat was the first heavier-than-air powered flight in Canada (and, in fact, the British Empire). But the first Canadian to fly — period? It was Casey Baldwin, McCurdy’s pal and a fellow protegé of Alexander Graham Bell. Alas, no Jell‑O coin ever commemorated him.

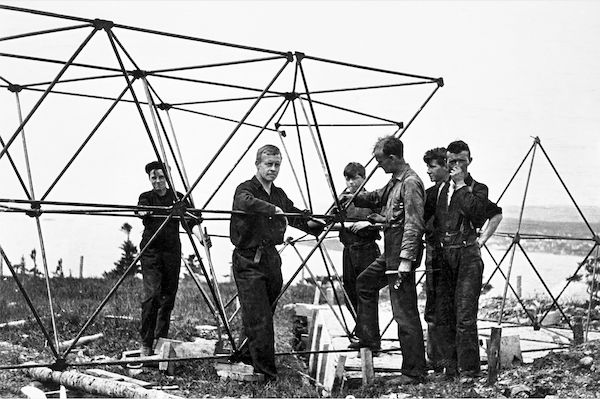

Casey Baldwin and team construct a tetrahedral tower atop Red Head, near Baddeck, Nova Scotia.

Nimbus Publishing

John G. Langley, a retired Cape Breton lawyer, believes it’s time Baldwin got some respect: for his first flight, almost a year before McCurdy’s, and for a string of other pioneering achievements in the air, and later on the water, that have gone virtually unnoticed. The result is Casey: The Remarkable, Untold Story of Frederick Walker “Casey” Baldwin. “It is a story of true genius,” writes Langley, “of epic accomplishment, and of epic failure to seize upon those achievements by a country too complacent about success and too indifferent about going its own way.”

To bolster his case, Langley has waded into a trove of hitherto unseen Baldwin correspondence, alongside papers archived at the Alexander Graham Bell National Historic Site in Baddeck, Nova Scotia. The documents are both the book’s strength and its weakness. They illuminate Baldwin’s enormous contributions to the great inventor’s work, as well as the deep personal affection Bell and his wife, Mabel, had for the young protegé. But the sheer volume of excerpts tends to blunt the book’s narrative thrust.

Casey Baldwin arrived at Bell’s Baddeck estate, Beinn Bhreagh, in 1906. And he came with an impressive pedigree: he was a grandson of Robert Baldwin, the giant of pre-Confederation Canadian politics, and held a degree in engineering from the University of Toronto. He also had an advocate in the person of Douglas McCurdy, a fellow U of T grad and native Cape Bretoner, whom the Bells had virtually adopted. Baldwin would spend the rest of his life at Beinn Bhreagh, marrying Kathleen Stewart Parmenter in 1908, raising a family, running the estate, and eventually dying there in 1948.

Langley nicely captures the crackling energy at Beinn Bhreagh (Gaelic for “beautiful mountain”) as the aging Bell and his inner circle tackled the problems of heavier-than-air flight. This circle consisted of Baldwin and McCurdy, of course, along with Glenn Curtiss, the engine builder, and Thomas Selfridge, an officer in the U.S. Army. At first, the working group, known as the Aerial Experiment Association, focused on Bell’s long-standing preoccupation with tetrahedral kite design. Before long, the men shifted their focus to powered machines, like the ones the Wright Brothers had been flying out of the public eye since 1903. It was aboard the first of these, the Red Wing, that Baldwin made his historic but unheralded flight. Eleven months later, in February 1909, McCurdy piloted the group’s fourth, aboard the Silver Dart, and flew into legend.

Selfridge died in September 1908, after crashing in a Wright Brothers machine. By 1911, Curtiss and McCurdy had broken away from Beinn Bhreagh and gone into business for themselves. But Baldwin worked with Bell until the inventor’s death in 1922. Bell’s final dictation, delivered hours before he took his last breath, urged his survivors and heirs to “stand by Casey as he has stood by us” and to “look upon Casey and Kathleen as sort of children and grandchildren.”

Milestones were not hard to come by in the infancy of aviation. The trick was to stay alive long enough to savour them, and to have the strength of character to soldier on through the inevitable setbacks. Baldwin had his share of stumbles. Chief among them was the failure of the Beinn Bhreagh team to convince the Canadian government to join them as a ground-floor partner in aircraft and, later, hydrofoil development. Baldwin and Bell also wound up on the short end of rancorous disputes over patents with other aircraft builders. These disputes — including one with the shrewd partners Curtiss and McCurdy — cost them untold millions.

But Langley wants to hail Baldwin, not pity him. The book enumerates a string of little-known successes Baldwin notched up in addition to the flight of the Red Wing. Most were accomplished in tandem with McCurdy. The two men co-fathered the commercial aviation industry in Canada when they founded the Canadian Aerodrome Company in 1909. A monoplane that the company built for an American customer was the first single-wing aircraft built in this country and the first commercial order in the history of Canadian aviation. The company’s inaugural flying machine, Baddeck No. 1, was the first entirely built in Canada. Baldwin was one-half of the first passenger flight in Canada, when he joined McCurdy aboard the Silver Dart for a test flight in the summer of 1909. Later, when his focus shifted to watercraft, Baldwin set a world speed record aboard a hydrofoil he had designed and built with Bell’s encouragement.

Add to these exploits Baldwin’s pivotal advocacy for the creation of Cape Breton Highlands National Park and the four years he spent as a provincial MLA, and you’d think he’d have earned a place in Canadian history — at least a place approximating McCurdy’s. Yet the only formal recognition he received during his lifetime was a 1946 honorary degree from the Technical College of Nova Scotia, which honoured McCurdy at the same time. Celebrations marking the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Silver Dart flight seemed to strike a template for the future: while McCurdy was feted as a hero, Baldwin was merely acknowledged — as something of an unexceptional supporting actor to a daring matinee idol. Langley allows that the two men had very different personalities, yet a note of bitterness creeps into his prose. “McCurdy’s story has become well known, attributable in part to self-aggrandizement,” he writes. “Casey’s, due to his implacable modesty, has not.”

Self-aggrandizing versus modest? Ambitious versus modest might be more like it. The two men were shaped by entirely different backgrounds: Baldwin a scion of Upper Canadian aristocracy, McCurdy a local Cape Bretoner whose family the Bells rescued from bankruptcy. McCurdy leveraged his fame as an aviator to forge distinguished careers in business and public service; he can hardly be faulted for pursuing a life that was a step up from the one he was born into. Langley, whose previous book was a biography of the shipping magnate Samuel Cunard, doesn’t need to diminish McCurdy’s stature in order to raise Baldwin’s: the evidence he marshals in support of Baldwin speaks for itself.

Nonetheless, Langley’s admiration for Baldwin — his gentility, his brilliance, his loyalty — is as palpable as his chagrin over the obscurity in which Baldwin languishes. While his passion occasionally gets the better of him, this lawyer turned biographer has to be admired for seeing an injustice and endeavouring to make it right. The upshot is ironclad: Frederick Walker Baldwin was an extraordinary Canadian who deserves a better shake from history. Case closed, Jell‑O coins or not.

David Wilson edited The United Church Observer from 2006 to 2017.