For many of us, what we know about so-called abortion travel dates from the story of Sherri Finkbine (now Chessen), which is where Abortion across Borders begins. Finkbine was an Arizona woman who hosted a local version of the children’s television show Romper Room. In 1961, early in her fifth pregnancy, she used sedatives that her husband, Robert, had purchased in Europe, unaware that they contained thalidomide, which had been linked to several fetal anomalies. Once the Finkbines realized that Sherri had ingested the drug, and on the advice of their doctor, they sought an abortion. Ultimately denied one in the United States, the couple travelled to Sweden, in 1962, to obtain a legal one.

Finkbine’s story is inextricably entwined with that of Suzanne Vandeput, although the latter woman, a Belgian, is less remembered in North America. In 1962, Vandeput, with the support of her doctor, husband, and family, euthanized her newborn baby with an overdose of sleeping pills. The child had been born with multiple anomalies, the result of thalidomide that Vandeput had ingested during her pregnancy. News coverage and public opinion polls showed strong support for Vandeput’s actions, and she was acquitted at trial.

Together the Finkbine and Vandeput cases prompted renewed public discussion of abortion. Many conversations revolved around perceived or expected disabilities, while others focused on ideas of motherhood, specifically maternal love, which is what the history professor Lena Lennerhed analyzes in her contribution to this collection of twelve timely essays. Indeed, as other historians, namely Leslie J. Reagan, have noted elsewhere, such discussions contributed to measured reform throughout the mid-twentieth century — reform that is now under sustained attack, especially in the United States.

Of course, abortion travel began long before Finkbine’s ill-fated pregnancy. Studies of abortion cases from the nineteenth century, for example, often entail journeys between towns and even across borders. What makes the Finkbine story different from those earlier ones, however, is the role of modern technology. Technology shrank our world throughout the twentieth century: transnational, interstate, and interprovincial travel became easier, more affordable. Indeed, it was Finkbine’s husband’s earlier trip to Europe that exposed her to the thalidomide, which had not been approved for sale in the U.S. It was also technology, in the shape of modern media, that carried Finkbine’s story around the world.

A series of measured mid-century reforms are now under attack.

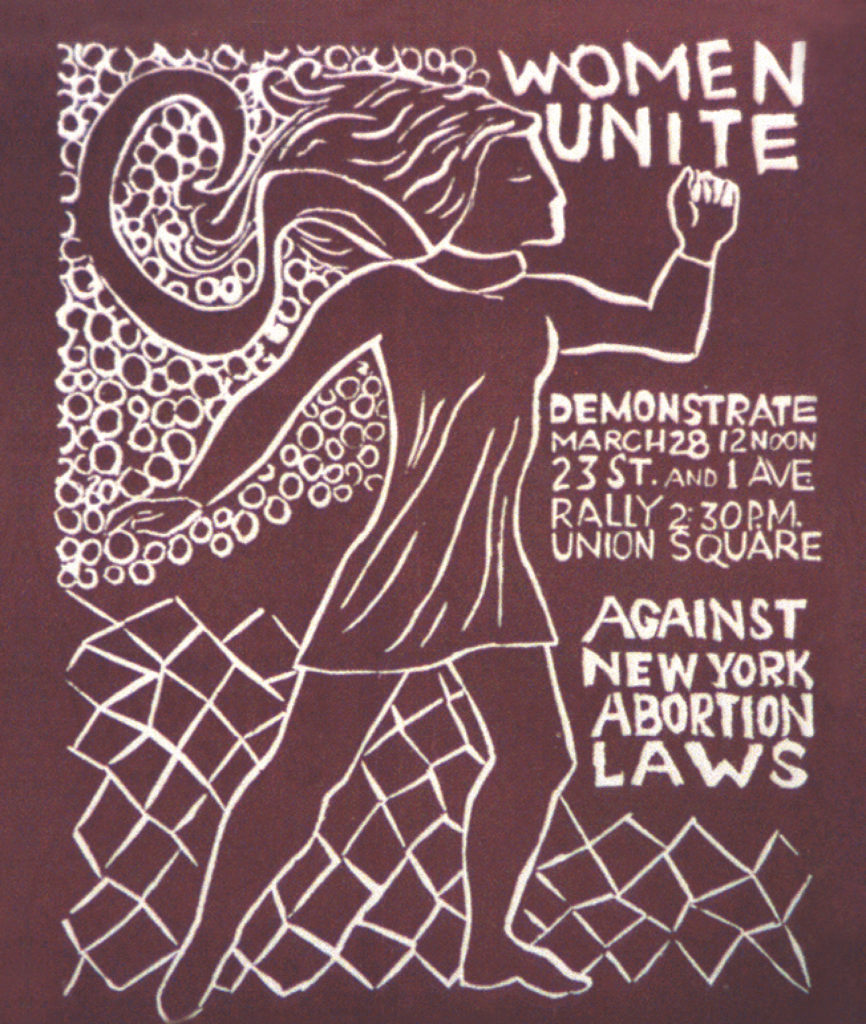

People to Abolish Abortion Laws, 1972 / Yanker Poster Collection / Library of Congress

The centrality of technology runs throughout Abortion across Borders, although both the editors and most of the contributors could have highlighted the theme much more explicitly. Nevertheless, readers can draw several important conclusions from the interdisciplinary analyses offered here. There are a number of strengths, including the introduction by Christabelle Sethna of the University of Ottawa, which contextualizes the volume in existing literature and advocates a transnational lens for the study of abortion travel.

Sethna, one of two co-editors, also examines the efforts of the Abortion Law Reform Association, in Britain, both before and after the 1967 Abortion Act, which legalized abortion in a number of contexts. The ALRA’s campaigning did not end with the passage of the law; as we know far too well, fights for abortion rights do not end with the passage of laws. Activists had to continue selling the law to a skeptical public and needed to contend with intense government scrutiny. As Sethna highlights, their efforts were complicated by an influx of non-residents travelling to Britain for abortions. Between 1968 and 1972, there was a dramatic rise in the share of abortions performed on non-resident women, from 5.5 percent to 30.8 percent, raising concerns that the private sector was capitalizing on vulnerable women. Importantly, Sethna does not focus only on the experiences of British women. If she had, an important element of this story would have gone uncovered: thousands of mostly northern European (but also some Canadian) women travelled for legal abortion services.

Mary Gilmartin and Sinéad Kennedy, both of Ireland, offer another particularly valuable contribution with their examination of “reproductive mobility,” a phrase that captures both “movement and stuckness,” as well as a variety of other reproductive experiences. In the Irish context, for example, forced adoptions have had a dramatic and lasting impact on women who were pregnant outside of marriage. As Gilmartin and Kennedy argue, the framing of travel as (in)voluntary mobility moves us away from terms like “abortion tourism,” which flatten the individual and structural reasons people travel for care, to say nothing of their experiences along the way. Gilmartin and Kennedy also consider reproductive mobility in the context of immigration. Fears around immigration “led to a moral panic about so-called citizenship tourists,” who were seen to be giving birth in Ireland to secure citizenship for their babies and families. Fears were so pronounced that a 2004 referendum approved a constitutional amendment to end jus soli, or birthright citizenship.

Fears around immigrants and abortion are, in part, connected to the role of technology: a shrinking world frightens some. With the ease of travel, borders have become more porous, less firm. The flip side of globalization is often an irrational, race-based fear of outsiders, which we see playing out through the emergence of far-right populism across Europe (and elsewhere). Many in the pro-Brexit camp, for example, seek to protect a specific vision of British identity. Yet it seems little thought has been given to the potential impact of Brexit (and similar movements) on medical tourism, and abortion travel in particular.

Niklas Barke considers the fragility of mobility rights as he considers the disruptive potential of different Brexit scenarios that “might complicate the lives of nonresidents,” even as support for women’s reproductive rights among the British public remains “strong.” His is one of several essays that decentralize abortion experiences in important ways. These chapters, including one by Anna Bogic, who studied at the University of Ottawa, push us to think about abortion travel in different ways. When it comes to reproductive travel, it is not just pregnant human bodies in motion. Bogic tells the story of American feminists who went to eastern Europe in the 1990s with the hopes of raising feminist consciousness. They brought with them “countless books and pamphlets that contributed to the formulation of a decidedly pro-choice position.” She shows how one text, in particular, had a significant impact, even as reproductive policies became increasingly restrictive throughout the period: excerpts of the pioneering 1970 book Our Bodies, Ourselves were first translated into Serbian in 1994, before the full text was made available in 2001. As laws became more restrictive in the 1990s, Bogic explains, “the OBOS philosophy and consciousness-raising principles became essential tools for the activists.” (Her work builds on that of Kathy Davis, who explored how Our Bodies, Ourselves circulated around the world in her 2007 book.)

While this is a rich volume that offers new and exciting analyses, there are a few noteworthy omissions. If Sethna is right — that we must study abortion travel through a transnational lens — we need to hear many more stories from the global South, as she acknowledges in the introduction. We also need to build on Barbara Baird’s chapter about a “globalized Australia” and talk more about race (beyond whiteness) and indigeneity, in order to fully capture the complexity of abortion experiences — and travel — globally.

Given the central role technology plays in this volume, the role of the internet is conspicuously absent. Like the telephone before it, the internet encourages communication and connection; it’s how people arrange abortions and abortion travel in today’s world. The internet, specifically social media, is also how the events and developments that affect abortion travel are broadcast in the moment — like the newspapers and TV shows that carried Finkbine’s story decades ago. (In my own work, I regularly encounter informal campaigns on social media to raise funds, and often to recruit drivers, for people seeking abortions away from home, many of them from Atlantic Canada.) Then there’s medical abortion — the abortion pill — which largely removes the need to travel. The abortion pill, which many argue is a game changer, has the potential to circumvent restrictive laws and ease access for millions, especially those who cannot afford abortion travel to safe providers — because of the costs, the missed work, the need to arrange child care. (Gilmartin and Kennedy do touch upon this potential, but only briefly.) Here, too, the internet plays an important role, with feminist-run sites like Women on Web mailing the pill around the world.

The abortion pill has the potential to change the object of abortion travel in dramatic fashion: from the pregnant body to a shipped medical treatment. Especially given today’s political climate, the impact of this technological shift deserves a much deeper consideration.

Shannon Stettner lectures in the Department of Women’s Studies at the University of Waterloo. She edited Without Apology: Writings on Abortion in Canada.