There is a trend in Canadian literature for novels to have at least one dead parent, a family secret or an incestuous relationship, and a moody undertone — bonus points for a harsh coastal setting. Lynn Coady’s latest novel, Watching You without Me, takes the expected CanLit gloom and gives it a new edge, transforming what could have been a slow and depressing tale of grief and loss into a deeply unsettling survival story. But this is more than just a thriller: it is a story of family, the challenges of caregiving, and loneliness, while also a cautionary tale about a man who turns out to be more sinister than he seems.

The novel opens after Irene, the mother of Karen, the narrator, dies of cancer. Karen is forced to return to her childhood home in Nova Scotia to manage Irene’s affairs and to get her mentally disabled sister, Kelli, squared away in a home. Having moved away to Toronto years ago, Karen is overwhelmed with guilt for abandoning her elderly mother and neglecting her sister’s care. But the guilt is mixed with frustration that she now has to look after everything by herself. It’s no surprise, then, that when one of her sister’s care workers, a man called Trevor, offers to help her, she gladly accepts.

The novel reads like a story your girlfriend might tell you over a bottle (or two) of cheap wine. Three hours, and 376 pages, will simply fly by. You believe her, and her story, but think some of it might be exaggerated. You suspect that you are being manipulated in some way, but you don’t care because the story is so riveting. The novel invites the reader in, placing us among Karen’s confidants by framing the narrative as a retelling: “What was wrong with you, friends always ask when I get to this part of the story.”

But Karen has already told us what was wrong:

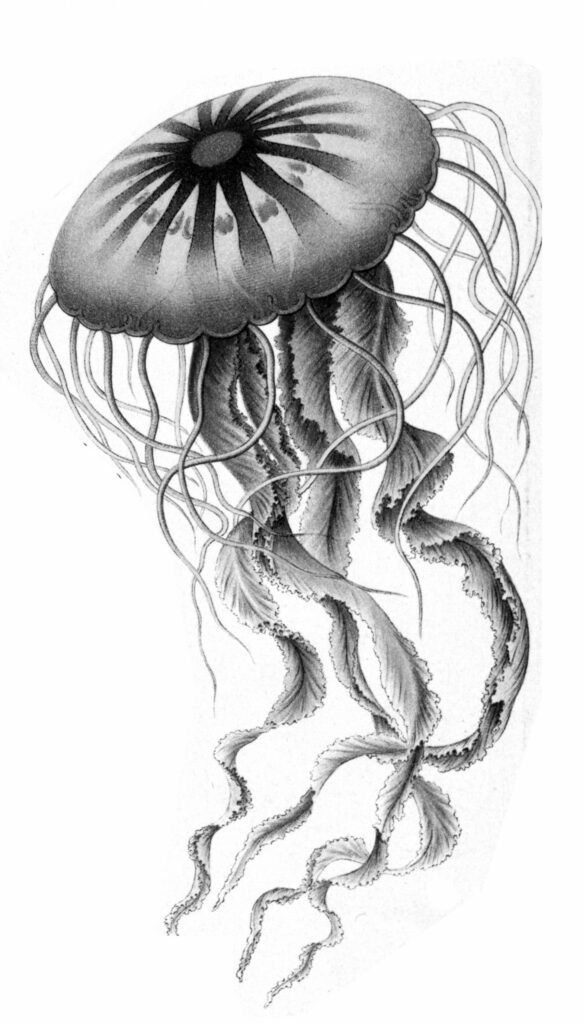

I was a creature of compulsion and nerve endings in those days, boneless. I felt like a jellyfish, blobbing along in the ocean — a cow flop of protoplasm that recoiled when touched but otherwise veered wherever unseen currents propelled it.

She felt like a jellyfish.

Adolf Giltsch, 1904; Library of Congress

We are placed inside Karen’s grief and it is all-encompassing. The spectre of her mother lurks in Karen’s thoughts, urging her to look after her sister. Though she is not alive in the novel, Irene is always present.

Karen rallies to care for her sister, but only until she can get Kelli into a home. She tries, like many caregivers, not to resent her sister. She also tries to accept the reality of what a life with Kelli would look like but finds the constant schedule juggling of care workers, community centre meetings, and doctor’s appointments hard to navigate. Living with her sister again lightens her mood, though, as Kelli brings some much-needed cheer to a mourning household: “It was also hard to feel aggrieved at the sight of Kelli, always overjoyed at the arrival of her bathers, rocking and smiling, repeating their names so happily and incessantly.” Karen begins to imagine that she might not move back to Toronto after all.

Despite Kelli’s “distinctive heh-heh-heh that properly belonged to a villain from a Scooby-Doo cartoon,” Coady manages to avoid making her cartoonish. Instead, she focuses on Kelli’s humanity and uniqueness, without patronizing or diminishing her. She is not a prop or a barometer for determining how her sister is doing but a person who has her own likes and dislikes. Kelli is an unusual sister for most, but a usual one for Karen, who realizes that she has missed her.

Before Karen can come to terms with her mother’s death and her sister’s needs, there is the problem of Trevor (or Trebie, as Kelli calls him). He is Kelli’s walker, who comes twice a week to take Kelli on a “poky, meandering turn around the neighbourhood.” From the outset, he is a suspicious and overbearing presence, frequently showing up uninvited. Though Karen is initially hesitant about him, he’s friendly and gets on well with Kelli, so she finds herself inviting him in for a snack. In desperate need of a friend herself, Karen soon accepts Trevor’s offer of support. “ ‘So I was thinking you could use some help,’ said Trevor. He put his other hand on the mower, crowding out mine. ‘Let me do this, then we’ll have a cup of tea.’ ” Trevor crowds out Karen’s objections and her sense of self-preservation, and we, the readers, are helpless to stop him.

The ease with which Trevor is able to insert himself into their lives is troubling. Coady draws our attention to a largely unregulated industry and demonstrates the class disparity between people who can afford upscale care homes and people who can’t. There is a cost associated with looking after your loved ones — the infirm, the elderly, the uniquely different or difficult — both financial and emotional. Watching You without Me highlights the drain as well as the reward of being there.

The novel falters somewhat because of the transparency of Trevor’s actions and how willingly Karen goes along with them. It is excruciating to see her let him in; she even jokes to a friend at one point that he “kidnapped” her and Kelli — which he did. He then bullies Karen into looking at other, more expensive care homes, which he deems better than the more affordable one Irene had picked for Kelli before she died. The red flags are waving ferociously from the minute Trevor arrives on the scene, but Karen consciously ignores them. It makes for a tense read.

The more she is led by Trevor, the more Karen learns that her mother wasn’t able to shut him out either. As the one who moved away, she feels complicit in his appearance in her mother’s life and wishes to punish herself for it. When Trevor does eventually go too far, it is Kelli’s firm “No Trebie” that gives Karen the strength to keep fighting. That, and a well-timed nosy neighbour who happened to show up at their door.

It is easy to immerse yourself in Lynn Coady’s worlds. Her characters are vividly flawed and charmingly realistic, and their lives are troublingly familiar. Whether she pulls you into the narration of a misunderstood, hockey-playing anti-hero, as in The Antagonist, or brings you along with a group of flawed individuals, as in her Giller-Prize-winning short story collection, Hellgoing, Coady is deeply respectful of her characters — if not always kind to them. As in her previous works, Coady enjoys throwing her creations into garbage situations to see how they will cope. Some handle it well. Others, like Karen, stumble along, until eventually they manage to scrape themselves out of trouble.

Megan Kuklis lives and reads in Prince George, British Columbia.