When the warlords of Bosnia were raiding villages and rounding up people to be shot, I was living some 150 kilometres to the east, in the relative safety of the Serbian capital under Slobodan Miloševic, and working as an intern at a Belgrade daily called Borba. Between the NATO bombing of Serbian targets in Bosnia in 1995 and the bombing campaign that was ahead of us — of Serbia and Montenegro over the war in Kosovo in 1999 — the Miloševic camp was making ever bolder moves and speeding up the takeover of the opposition media. Borba was the last daily to come under the regime’s thumb; it became Naša Borba when the entire newsroom rebelled against the new imposed directorship and continued to publish with greatly diminished capacity. I kept working, along with the rest of the last intake of apprentices to Naša Borba, wondering for how long the defiantly independent paper could pull it off, and what would come first: running out of money, a knock on the door by the state security force, or the NATO bombs. (Spoiler: it was the bombs.)

Those of us who have left countries with eventful histories and moved to Canada carrying a set of loyalties to the liberal democratic ideal have forged those loyalties in trials by fire. In the West Balkans in the 1990s, democratic liberalism and internationalism were the most fragile of all political views, in sharp contrast to the rise and rise of chauvinist populism. Like many other immigrants, I have first-hand knowledge of how unfinished the Enlightenment project actually remains. Where we once lived, the autonomy of scientific and philosophical inquiry is having to reassert itself over and over. Where we once lived, universalism is suspect, impossible. Where we once lived, the past remains enchanted, mythologized. It was we, as Peter Pomerantsev argues, who first lived through a post-fact, post-value, and post-hope era, which many Western countries are now experiencing.

For a person in a writing profession, Canada has in many ways been a reprieve — from having to defend freedoms to think and speak, to assemble with like-minded citizens, to petition, to disagree. Double-think, public contrition and self-criticism, ideological re-education, blacklists, moral-political suitability, ethnic essentialism, racial pride — I never thought I would see these things become ordinary here. But times have changed fast and radically in the chattering professions. Liberties are never ensconced for good, it turns out. They last only as long as the people who are willing to keep them alive.

When did the dams give way? Was it in November 2017, when Lindsay Shepherd, a teaching assistant at Wilfrid Laurier University, was questioned by senior faculty and administrators for streaming a clip of the psychology professor Jordan Peterson, from The Agenda with Steve Paikin, in her classroom? A particularly precedent-setting aspect of that case was that it brought out a surprisingly large number of people who were fine with seeing her, a member of the most vulnerable teaching precariat, threateningly interrogated to the point of tears — fine with her having to defend her decision to share with her students a topical video clip from a publicly funded TV network’s flagship program. There is no such thing as unlimited freedom of speech, of course, but overnight, the goalposts of what’s permissible in conversation narrowed considerably — at an institution whose purpose is to keep them open wide.

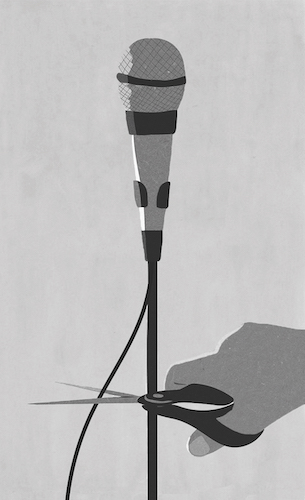

Is this thing on?

Holly Stapleton

Or was it the reactions to Peterson himself that lowered the threshold, after he came out against Bill C‑16, which added gender identity to the Canadian Human Rights Act in 2017? Every announcement of a Peterson appearance since has been followed by an online hive of people — many of them in the academy, the media, the arts — advocating for its immediate cancellation. He does not guest-speak at Canadian institutions as much these days, but Carlton Cinema, in Toronto, recently called off a run of Patricia Marcoccia’s CBC-funded documentary on the professor, because it made some employees uncomfortable.

Something has hardened since the Lindsay Shepherd scandal. And from the perch of 2020, we can look back almost with nostalgia on the era when the outrage, the calls for no-platforming, the compelled speech came from the right. Recall the reaction against Svend Robinson, the New Democrat MP who, in 2000, questioned references to God in the Constitution. Or remember Little Sister’s, with its books and magazines seized at the border by customs agents throughout the 1990s and early 2000s. There was also Michael Healey’s play about a fictional Stephen Harper, Proud, which Tarragon Theatre blocked in 2012, because a board member was certain the prime minister’s feelings would be hurt to the point of legal action. Each Remembrance Day, certain Sun columnists (and hockey personalities) would complain that too few people on our streets wear poppies. A few summers in a row, we heard calls for the city to defund Toronto Pride for allowing Queers Against Israeli Apartheid to participate. Add to that the usual slew of complaints to remove this book or that video from public libraries, or Harper’s muzzling of the government scientists who work on climate change. How has it usually played out? Institutions have stood firm, muzzlers have lost elections, people have kept their jobs, writers have continued writing, and activists have remained active.

Today, the consequences of unpopular speech are swifter and measurably harsher than they were even a few years ago. What’s also new is the tenor of the left’s embrace of censorship — often of fellow leftists. Cases are piling up fast, but one of the most stunning remains the removal of a Sky Gilbert play from Toronto’s Buddies in Bad Times Theatre, in retaliation for a couple of unrelated posts on Gilbert’s personal blog, in which he expressed some dislike for the writing of a younger member of the LGBTQ cohort and for the general culture of wokeness. Lengthy “Do better!” threads followed on Twitter, with the magic word “harmful” especially prominent. And lo, within days, Gilbert’s previously scheduled, announced, and promoted-in-brochures anniversary reading of Drag Queens in Outer Space was forthcoming no more. (Shakespeare’s Criminal was gone too, but that came later.)

How is this even legal? I’ve lived with both left and right authoritarianism, but I have never witnessed such a swift removal of a play — not even under Miloševic, when theatre was a centre of opposition activity. And what does this say about how online activists understand critics and criticism and what they are for?

The wave of madness rose even higher late last year, around the time Meghan Murphy spoke at the Palmerston branch of the Toronto Public Library. Murphy edits the website Feminist Current, which is available online for everyone to see, along with her past writing and public appearances. Yet in spite of there being no actual evidence for it, the smear of hate speech keeps following her, due to the relentlessness of certain activist groups. Just what are Murphy’s positions? For one thing, she is in favour of the Nordic model when it comes to regulating prostitution — an unpopular approach among the online left. Her view on porn derives from the work of the radical feminist Andrea Dworkin, which makes her additionally unpopular. And Murphy is often heard civilly criticizing Bill C‑16 for opening up any female-geared service, grant, or award to anyone who self-identifies as a woman, no questions asked, which makes her — for the threshold has fallen that far — incendiary.

There are already unfortunate consequences to Bill C‑16: British Columbia’s world-renowned vexatious litigant Jessica Yaniv is one. There are also reports that Corrections Canada is transferring inmates to women’s facilities based on self-declaration. But according to many on the vocal left, a number of prominent CBC radio personalities, Toronto’s mayor, and all but one of the city’s councillors, to even suggest that what’s already happening might conceivably happen is to engage in hate speech that harms all trans people. After Vickery Bowles, Toronto’s chief librarian, stood her ground and did her job as the head of an institution dedicated to free inquiry and other Charter basics, my own councillor, Kristyn Wong-Tam — who then forever lost my vote — called for her colleagues to join her in asking for a review of the library’s room booking policies. And they did so, in a show of grandstanding and unity resembling a near-perfectly whipped politburo session.

And on it continues: Will Johnson was fired as literary editor of The Humber Literary Review because around the time of Murphy’s TPL event, he tweeted expressing some displeasure at the activists’ tactics. That is not allowed, it turns out. As the Post Millennial reported, Johnson received a letting-go letter from one of the review’s founding editors, which explained that his criticism of a very specific corner of trans activism would lead inevitably to a rise in transphobia. Off he goes.

In Vancouver, the Sun and the Province decided to unpublish a not particularly convincing opinion piece by an Alberta university instructor, who argued for reduced immigration totals. When did it become unsayable, beyond the pale, nay, fascism to question national policies? Our system is fairly restrictive as it is; where Canada beats other countries in openness is in its per capita intake. But the author, Mark Hecht, argued those numbers should be lower. As a country, we have weak population growth, which has a detrimental effect on our economy. So it should be easy to rebuke Hecht’s argument in a response op-ed. What touched some sensitive nerves was his questioning of the idea of continuous ethnic diversification, and whether it leads to effective integration and a cohesive society. Hecht, like many conservatives around the world, favours cohesion and community over diversification and freedom of the individual. So: kaput he was. The hive decided his piece was an example of white supremacism, and the newspapers eventually removed the piece with apologies. The editors didn’t offer multiple different counterpoints showing why the original op-ed was clueless. Nothing but a complete removal would do.

Across the border, in the land of the First Amendment, things are moving in the same direction. Ian Buruma lost his job as editor of The New York Review of Books for publishing that treacly essay by Jian Ghomeshi. The New Republic decided to unpublish Dale Peck’s screed about presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg. The San Francisco school board voted to board up some Depression-era murals depicting, unflatteringly, the life of George Washington, because some argued they could traumatize African American and Native American students in the year 2020. A Chinese student group managed to get a pro-Tibet panel discussion cancelled at Columbia University. And as I’m writing this, a college professor in Massachusetts has been fired over a joke on his personal Facebook page, in which he suggests Iran make its own list of significant cultural sites to attack, for example the Kardashian residence or the Mall of America.

This is new. The quality and quantity of punishments for expressed opinions or aesthetic choices are different than just a handful of years ago. This reminds me of a different time and place. What is happening, Canada? What are we hurtling toward? Perhaps a time when the left will see hate speech in every disagreement, while the right will continue to run the world. A time when the autonomy of science and art will be abandoned in favour of a more pressing societal value. A re-enchanted time, when journalists and historians look feeble next to the mythmakers. A time that we immigrants from countries with eventful histories know well and can spot from afar.

Lydia Perovic moved from Montenegro to Canada in 1999. Her novella, All That Sang, is about a French orchestra conductor.

Related Letters and Responses

Sky Gilbert Guelph, Ontario

Beth Kaplan Toronto

Deborah Jones Vancouver