Arguably, the three most important events in Newfoundland history are as follows. First, in 1497, John Cabot, a Venetian explorer, “discovered” the island on behalf of England. (The first European to actually visit Newfoundland — and America, for that matter — was Leif Ericsson in approximately 1000.) Second, in 1949, Newfoundland joined Confederation, thanks in large part to Joey Smallwood. And third, in 1992, federal fisheries minister John Crosbie announced a moratorium on taking cod. That prohibition was supposed to last two years, time to let the stocks recover after decades of overfishing. In fact, it remains in place, with the exception of a small, heavily regulated recreational fishery. For many families, 1992 is a borderline separating the traditional way of life from now. A small number of fishers have managed to survive, moving on to crab for the most part, but fewer and fewer Newfoundlanders are taking to the sea to fish, even for recreation. Knowledge of the old ways is in danger of slipping away.

Jenn Thornhill Verma — an expatriate Newfoundlander, now living on mainland Canada with her young family — considers where the province finds itself today with Cod Collapse. Verma’s own connection to the fishery was severed in 1987, five years before the moratorium went into effect, when her grandfather died. Her father, like many baby boomers, found work outside the fishery. “I did not want to go on the water,” Verma’s father, an X‑ray technologist, explains. “My father was shipwrecked too many times to like that.”

By now, enough ink has been spilled about the rise and fall of the North Atlantic cod fishery to fill an ocean. In 1998, Michael Harris published perhaps the most authoritative autopsy with his brilliant Lament for an Ocean: The Collapse of the Atlantic Cod Fishery. Harris’s book is so authoritative, in fact, that former premier Beaton Tulk handed out copies to federal ministers, hoping to impress upon them the toll that the moratorium was taking. Mark Kurlansky helped popularize the commodity history genre in 1997 with Cod: A Biography of the Fish That Changed the World. Specialists have also given their insights, including the former fishery executive Gus Etchegary, with Empty Nets: How Greed and Politics Wiped Out the World’s Greatest Fishery, and the Memorial University professor Dean Bavington, with Managed Annihilation: An Unnatural History of the Newfoundland Cod Collapse. Along the way, there have been countless personal biographies and documentaries about the ban’s impact. At this point, one’s tempted to ask, What else is there left to say?

Verma wisely attempts to make the political personal in Cod Collapse by focusing on the moratorium’s effect on her family. She begins with a trip to Little Bay East, on the south coast, where her grandparents’ old house has sold. “As I stand here now,” Verma laments, “outside the former Thornhill family home, I’m gutted thinking the house is no longer ours. All that remains under our namesake is in the graveyard.” It is a touching moment, made all the more melancholy by the fact that her father is receiving palliative treatment for cancer — another familial connection about to be severed.

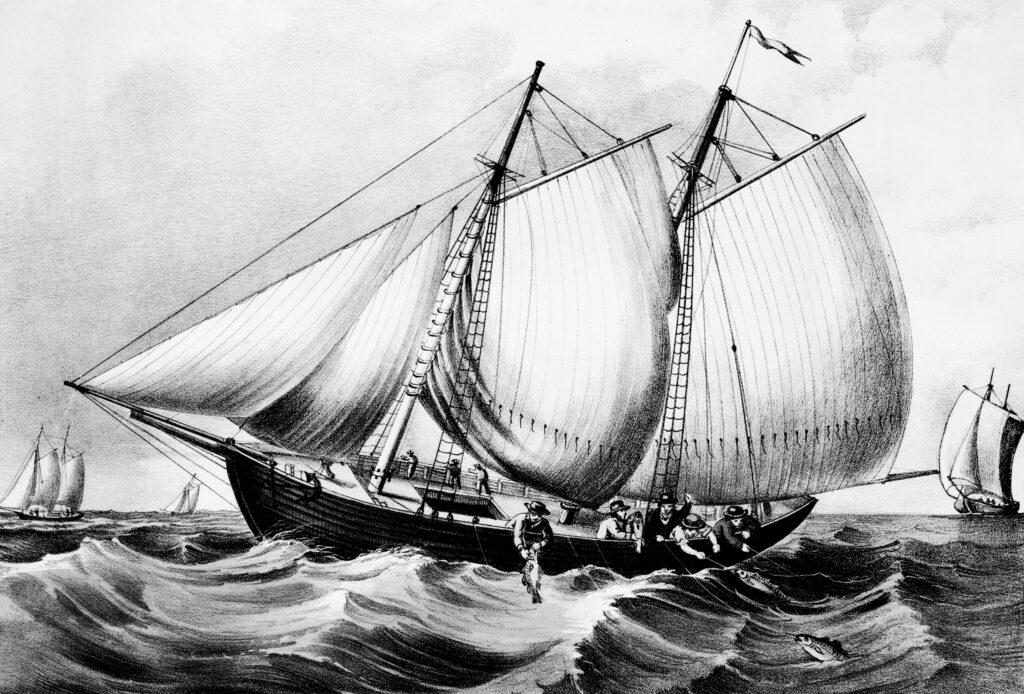

When knowledge of the old ways starts to slip away.

Currier & Ives, 1872; Yale University Art Gallery

As her ties to the island fall away, she finds herself in a position similar to that of many other Newfoundlanders trying to elucidate what connection, if any, is left. In a word, not much. Cod Collapse is a sombre and accurate depiction of a province that is a shadow of its former self. Although it enjoyed a brief post-moratorium period of resurgence and prosperity when oil prices were high, from the mid-2000s until they crashed in 2015, even this windfall was quickly squandered.

In addition to moments of personal meditation, Verma puts in considerable legwork — going far afield from St. John’s, even as far as Quirpon on the northern tip of the island — to profile those who have stuck around. “Tourists are the new cod,” as one entrepreneur, who plans on converting an old fish plant in Salvage into a brewery, puts it. Then there’s Brad Watkins, who left the fishery to run an RV park near Springdale in central Newfoundland. Watkins was once considered to be the future, and perhaps even the saviour, of the fishery. His first boat, the Atlantic Charger, a marvel of modern nautical technology, sank in Frobisher Bay in 2015. After another close call, he decided it was time to move on. Other “saltwater cowboys” have fared better. Wayne Maloney leads a lucrative venture taking tourists out to see whales, puffins, and icebergs. There’s also April MacDonald, who documents outmigration by photographing empty and abandoned houses on the island’s west coast.

Cod Collapse is part history, part memoir, part travelogue; it casts a wide net but doesn’t plumb the depths. Verma spends much of her time getting readers up to speed on local history but doesn’t really break new ground. Watkins’s story, for example, was widely reported in Atlantic Canada — tackled by Jim Wellman in a four-part series for Navigator magazine and in his book Challengers of the Sea. And though it would be unfair to expect any single author to provide actionable solutions to Newfoundland’s many plights (anyone capable of doing that would surely deserve the Nobel Prize in Economics), it is not unreasonable to expect a book on the moratorium to chart new waters.

Cod Collapse ends as sombrely as it begins. “This is it,” Verma reflects. “I was leaving behind a place that defined me with no plans to return to it; if I did, it would likely be without my father riding shotgun.” Ultimately, she leaves the reader with a few points to consider, mostly focusing on whether Newfoundland can maintain its traditions and culture of seafaring — even if the cod never truly returns. For the most part, though, she just nibbles around the edges of the question.

What’s perhaps worse, Verma occasionally falls into sentimental clichés about the province and its people: “Commonly called ‘The Rock’ for its windswept rockfaces, jagged and exposed to the North Atlantic Ocean, you could almost say its people are like rocks, too — sharp, solid, and reliable.” Newfoundland is full of stalwart people, such as Verma’s father and grandfather, but it is also full of scoundrels. One old fisherman tells Verma about leaving the house before three in the morning to check his salmon nets, lest thieves in speedboats get to them first. And there’s a particularly awkward exchange with the new owners of her grandparents’ house. “In Newfoundland and Labrador, generally speaking, if you meet a stranger at the corner store or while asking for directions, they are just as likely to tell you their life story as they are to invite you over for coffee or tea,” she writes. “Except in this case.” One can sympathize with Verma’s sense of estrangement and sorrow as the new owners politely but curtly neglect to invite her inside this once familiar home. Nonetheless, laying her dashed expectations on these unfamiliar people seems unfair — as if they haven’t lived up to the ideal of Newfoundland hospitality that mainlanders see in those slick tourism ads.

Brad Dunne is a freelance writer and editor in St. John’s.

Related Letters and Responses

Jenn Thornhill Verma Ottawa