Conceptual distinctions are easy to make but hard to implement. An old professor of mine, who specialized in hermeneutics, liked to say of the difference between theory and practice that in theory it was a clear divide, but in practice . . . I imagine that joke continued to elicit a chuckle among his students long after I graduated. But, of course, paradox can be instructive.

In theory, the difference between solitude and loneliness is clear; in practice, there are overlaps and shades of difference that resist any bright-line divide. You can be alone and never lonely. You can experience the throes of alienation at a crowded party. Maybe most of all, you can mesh these modalities together in the phenomenological stew that we call everyday life.

You wouldn’t know this from the way many people, from respected academics to some less than rigorous journalists, have gone on about the challenges of social distancing, self-isolation, and outright quarantine that have marked the pandemic. Forced to retreat behind closed doors, mandated upon penalty of fine (or worse) to refrain from social contact, many worry their solitary condition might be actively harmful. Flip a coin: Alone or lonely?

The latter is presumed to be always bad. A recent piece in The New Yorker, about the negative effects of coronavirus-induced isolation, included the following scare-inducing sentences:

Walking the fine line between solitude and loneliness.

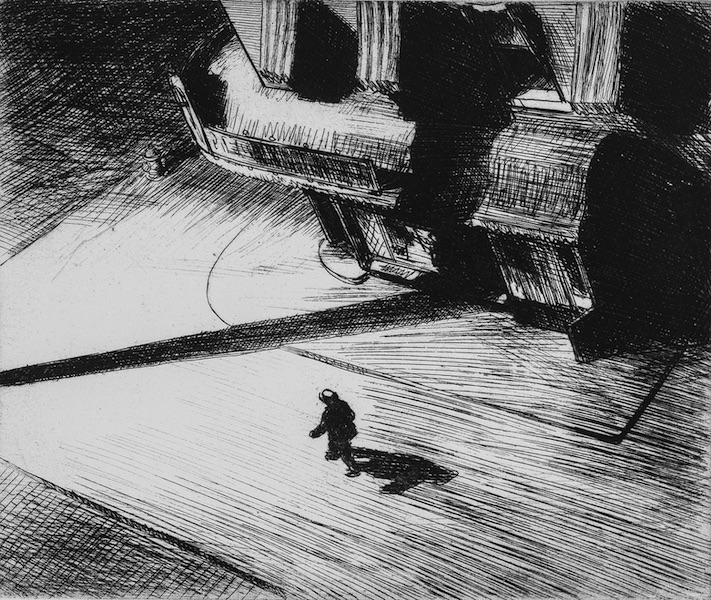

Edward Hopper, Night Shadows, 1921; Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper; Artists Rights Society; SOCAN, 2020

Studies show that the health consequences of prolonged loneliness are equivalent to smoking fifteen cigarettes a day. . . . The condition can prompt cardiovascular disease and stroke, obesity, or premature death. It is associated with a forty-per-cent increase in the risk of dementia. . . . Loneliness also increases the risk of clinical depression, which has its own statistical dangers.

I smoke only cigars myself, but it’s weirdly reassuring to be able to quantify aspects of this existential threat with the universal unit of risk — the cigarette — which feels just as inventive as “millihelen,” the notional measurement of beauty needed to launch just one ship.

Yes, it’s true that enforced loneliness can be a terrible burden. Why else, after all, would solitary confinement count as among the worst of the non-violent punishments for prisoners? But to suggest, per contra, that solitude is inherently enjoyable for those with the correct inner resources, longing for removal from stimulation, is likewise too pat, even if it is a situation cherished by writers. Evelyn Waugh depicts his hapless protagonist Paul Pennyfeather, clapped in jail for unwittingly conspiring in white slavery, as enjoying the freedom from the travails of daily newspapers and settling into a pleasant routine. Montaigne declares himself completely happy only while isolated in his study. Even Virginia Woolf’s own little room is depicted as a respite, not a sentence.

Writing is an inherently reclusive undertaking, so it’s no surprise that writers frequently laud the features of solitude. Most of them, under normal circumstances, expend considerable effort to secure it, to carve out space from the hectoring demands of the everyday. But what is sometimes forgotten by those who long for isolation is that the battle to be productively alone makes sense only if the background conditions are themselves social. Otherwise, it is not escape but real imprisonment. Take away the choice to be solitary, in other words, and what was freedom is now a trap.

There are many stirring prison texts on record, from Epictetus and Boethius to Wilde and Solzhenitsyn, with stops in between at de Sade, Gramsci, Jean Genet, and a host of others, in fact and fiction. It was Lovelace who penned the immortal lines “Stone walls do not a prison make / Nor iron bars a cage.” He was locked up in Gatehouse Prison for just seven weeks, though, and his poem was more performative than plaintive. Maybe more poignant is a recent advertisement for a tax-return service in which a client, asked about his employment status, glumly says, “Well, not all prisons have bars. Some have casual Fridays.”

Which comes closer to the original distinction’s fuzziness. If you can feel free in an actual prison, or exult in your chosen solitude, you can also be part of “the lonely crowd,” the phrase that the sociologists David Riesman, Nathan Glazer, and Reuel Denney used to title their 1950 bestseller about social fracturing after the Second World War. Seventeen years later, Harry Nilsson wrote, “One is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do.” But he wasn’t talking about being tossed into the hole at Fulsom — though “doing a number” does somehow suggest a prison stretch as well as the blues. He was, rather, lamenting the routine aloneness of being unloved. Don’t forget the next lines: “Two can be as bad as one / It’s the loneliest number since the number one.” Not only can you be alone in a 1950s crowd, you can be alone in a 1960s relationship.

So here we stand amid the crisis, subject to state-sanctioned measures of enforced isolation. One widely circulated meme, captioned “We are all Edward Hopper paintings now,” shows the artist’s famous lonely figures. But when I look at those images, I don’t see loneliness — I see sober solitary reflection and, sometimes, an inversion of the lonely crowd idea, namely odd gatherings of the freely isolated. Hopper’s most valued works, Nighthawks and Chop Suey, depict intimacy among strangers or near-strangers. Even Western Motel shows a female figure looking directly at the viewer, with a car waiting outside. These are scenes and places that, in our current isolation, we cannot inhabit: an all-night diner, a Chinese restaurant, a motel on the way to somewhere.

What we miss now is the ability to be alone when we desire, then to socialize when we desire, together or alone. Before the restrictions on air travel went into effect, I used to fly a great deal, around North America but also to Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Australia. I always took pleasure in the odd transitory anonymity of airport bars, just as I would enjoy a trip to a greasy spoon closer to home. Glenn Gould, highly averse to human contact, nevertheless counted on his visits to the twenty-four-hour Fran’s Restaurant near his place on St. Clair Avenue, in Toronto. He could live inside his head, because he could walk outside his apartment.

A taste for solitude is unevenly distributed in human populations — we know this. The infamous Myers-Briggs personality index includes introvert/extrovert as one of its four scalar elements, but that binary is far too simplistic. Whenever it’s deployed, I hear echoes of another New Yorker piece, this one titled “I’m Not an Asshole. I’m an Introvert.” Under the right circumstances, the satirical narrator explains, “I actually do like parties.” But the circumstances are, indeed, specific: “That being said, once I’m at a party, you won’t find me introducing myself to people, or thanking the host for having me, or going out of my way to show an interest in what someone else wants to talk about if it’s not me and my life, or any of that other extrovert stuff.” Suffice to say, these are not the right circumstances.

In the seventeenth century, the French mathematician Blaise Pascal wrote, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” Today, that dictum feels sound but also leaves some big questions unanswered. May I leave the room when I wish? Otherwise, it’s a prison, not a choice. Are there books in there, or a video game, or a computer? Do those things not count as quiet? If they don’t, am I being asked to meditate? And if so, meditate on what, exactly? Myself? The room? Myself sitting in the room? All of the above?

There are those who simply don’t have time, energy, or thought to spare for such questions — the unwillingly homebound, the immobile elderly (such as my own father), the incarcerated and the unhoused, the very ill, and, of course, their various selfless caregivers. But for many of us, the answers depend, I think, on one’s essential proclivities. Personally, I like a lot of time away from other people, including my most beloved family and friends. Yet, like Mordecai Richler heading to the old Ritz-Carlton Hotel bar after a solid day of writing, I welcome meeting some friend for a drink or dinner, or even just a solitary drop‑in at a local watering hole. Singleton lunch is excellent, singleton dinner is okay (if you sit at the bar). I hate offices, but I couldn’t function happily without the office fixtures of email and phone. And so on. We all have our own fine tuning on these points.

What is most fascinating about our current degree of self-isolation is how we are reimagining the very idea of connection. People are moving in-person meetings and lectures online, of course, but they are also organizing virtual happy hours, hymn singalongs, and dinner parties. A few weeks ago, I joined my two brothers and their families for a remote get-together to mark something called International Cocktail Day. Our little party wasn’t all that international, but we live in three cities across three time zones and two countries. The question then becomes: Why hadn’t we done this before? In the internet age, isolation works, strangely, to annihilate distance.

Aristotle said this about solitude: when it is humanity’s nature to be zoon politikon (a political animal, a phrase almost universally misapplied), to live alone is to be either a beast or a god. We live and die by and through our social connections and obligations. We need family and friendship, community and care. We are less than ourselves without these; our inherent essence is thwarted. At the same time, as suggested in Book X of his Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle argues that the highest happiness allowed humankind resides in our solitary contemplation of the eternal, an experience that cannot be shared.

This is the basic paradox of human existence. We need to be together, but something in us wants to be alone. It’s relevant that Greta Garbo preferred “I want to be let alone” over her much-quoted line from Grand Hotel: “I want to be alone.” She insisted, like any good philosopher, that this was a distinction embracing a big difference. To be let alone is to be relieved of distractions and irritants, nagging hangers‑on, and, in her case, insistent total strangers eager for contact with the icon rather than the real woman, whom they didn’t know. To be alone is, inevitably, to be alone with one’s thoughts, the ever-unfolding narrative of selfhood.

I recall reading a short story, I think by Somerset Maugham, in which the protagonist is seated in a restaurant near another solitary diner, who starts talking to him. At first, he finds it surprising that this otherwise apparently self-contained man should suddenly crave his company. It turns out that the man has an urge to confess — an act for which there must always be some kind of audience, including especially the vicarious office of priest in communication with God. Albert Camus gets this exactly right in The Fall, where the “judge-penitent” Jean-Baptiste Clamence importunes a hapless drinker in an Amsterdam saloon. Bartenders everywhere surely know the feeling: here comes another judge-penitent in pursuit of unburdening! The solitary are not alone if they can find an ear, and not necessarily a sympathetic one, for them to bend.

Years ago, I was sitting alone in one of my own favourite restaurants when the very friendly owner, Jean-Pierre, offered me a newspaper to pass the time. But I didn’t want it. I wanted to be alone with my half-formed thoughts and reflections, my memories and aspirations, the way I used to be in nearly empty libraries during graduate school or on long train trips around England, France, Canada, and Scotland. But maybe I misremember those times; maybe they were less frequent, more temporary than I imagine. T. S. Eliot said, “Humankind cannot bear very much reality.” We are all learning, in these strange new days, that reality now means some form of isolation. Whether that translates into loneliness or solitude is, as always, the paradox that marks the human condition generally. It can be addressed only by each of us alone in our thoughts.

Mark Kingwell is the author of, most recently, Question Authority: A Polemic about Trust in Five Meditations.