After eighteen books of fiction and four of non-fiction, David Adams Richards has published his second collection of essays. Richards, whose Mercy among the Children won the Giller Prize in 2000, has put together twenty-eight essays, in two blocks, some culled from as far back as thirty-five years ago. Some have previously appeared in newspapers and other periodicals, while others are published for the first time.

A batch of poems serves as a bridge between the two blocks. For the most part, the poetry is slight, though it conveys a strong sense of place. Richards, a fan of the late Alden Nowlan, a fellow Maritime poet, does offer a succinct octet (“Betrayal”) and an ironic, didactic poem (“The Man Who Loves My Children”), about a writer whose only compassion for children and people in pain is found in his fiction, not in his real life. There is a poem about travel, a prosaic one about networking, a platform poem in honour of Milton Acorn, and some descriptive lyrics that have not quite found a way to be both lyrical and moving simultaneously. The best poem is the autobiographical “The Journey,” about a man’s quest for wisdom, which points to one of the merits of the book as a whole: Murder and Other Essays is a rough map of a distinguished Canadian’s mind and heart. Like many maps, it is unsettling at times, detailed at others; this one is shaped by Richards’s moral sense and down-to-earth, unfussy, even awkward style.

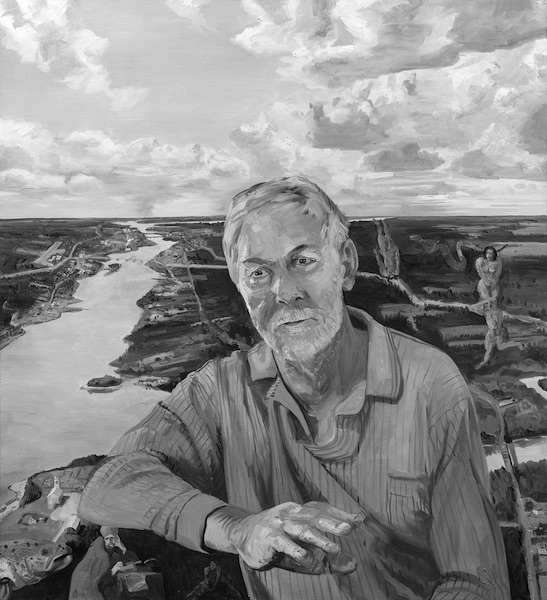

A champion of the working class.

John Hartman, David Adams Richards above the Bartibog and Miramichi Rivers, 2018; Nicholas Metivier Gallery

Richards’s literary brand is qualitatively and quantitatively preoccupied with moral choice — a point underscored by the collection’s first essay, “Murder,” which makes for an intriguing, if somewhat chilling, entry point into an assemblage of memories and meditations. Written in 2009, it is a flashback to a July night, when Richards picks up a First Nations hitchhiker on a highway along the Miramichi River, in northern New Brunswick. The man has just been released from prison and is travelling home to his reserve. The radio plays “Dust in the Wind,” with lyrics that articulate the futility of all our dreams. The stranger agrees with the singer: even if God exists, we are too tiny for him to care about. He has led a horrific life, and he tells Richards how he plans on murdering his cousin. There is some black humour as he contemplates how to commit the crime — by axe, by gun, by arson — but Richards turns the situation into an opportunity for ethical reflection. Murder is a form of self-aggrandizement: you know you are breaking a law beyond human law.

Richards does not report the potential murder to the police, and he agonizes over this failure. Months later, he learns that the man, now arrested for something else, did not follow through, stopped instead by the sight of his cousin’s sleeping children.

Both children and innocence figure significantly in Richards’s fiction, as they do in the works of William Blake and Charles Dickens. Indeed, it was Oliver Twist, with its soul-stirring exactitude of truth, that prompted Richards to be a writer, though he finds in his essays other templates for compassionate honesty, at one point noting that it was Tolstoy (also a fan of Dickens) who could see the heavens in ditchwater.

While Richards has been writer-in-residence at various universities, he did not complete his own bachelor’s degree. He seemed to have been soured on academia by what he observed growing up. “There are two things detrimental to the soul,” he writes. “Ignorance coupled with arrogance, and knowledge without compassion.”

Richards is a fervent champion of the working class, “the backbone of the nation.” And this collection is filled with examples of the heroes who “keep Canada going,” including the men in the 1959 Escuminac fishing disaster. “Boys no older than fifteen made sure their little brothers and fathers were saved before themselves,” he writes of the thirty-five men lost while drifting for salmon in Miramichi Bay. “Small boats turned back into the teeth of the storm, and refused to abandon those in trouble.”

With “The Shannon,” about the Escuminac disaster, he contemplates a dysfunctional family, headed by a man living with PTSD, the result of a head wound in Korea. The father to two sons, he suffers from blinding headaches, which he attributes to “a big gold nugget” that will someday exit his nose and make his family rich. The man perishes in the storm, having already seen his older son swept away. At the end, the surviving younger son speaks in a manner reminiscent of Morley Callaghan:

For you see, in the end my dad never lied. He did have a gold nugget. It wasn’t in his head — I know that now — I know that’s where all the pain and sorrow were, all the sudden flashes of despair — but the gold nugget was there, too, wasn’t it. My brother always knew it. It was in his heart.

At times, Richards’s view of the working class is overly simplistic and over-romanticized, rooted as it is in the implicit belief that only manual labour can be honest, decent, and noble. In fact, every class of people has those who are nasty, brutish, and deplorable; social class has nothing to do with human nature or character (vide the president of the United States). Still, Richards draws his heroes from mean lives of poverty and abuse. Several of his uncles, and the uncles of his wife, began working in the woods as early as twelve or thirteen. His widowed grandmother, a fierce feminist long before feminism became fashionable in Canada, ran a movie theatre in the 1920s, in the small New Brunswick town of Newcastle: “Trying to keep her head above water after they tried to at first buy her out, then foreclose on her mortgage with a corrupt and in-debt manager of the Royal Bank, and then finally bomb her out.”

Richards celebrates other real-life heroes with no less colour or conviction: Alden Nowlan was a “hard-drinking, chain-smoking, complex, irascible, irritating wonder of a man.” The writer Malcolm Lowry was “belittled as a child, terrified of sex, laughed at as an adult, deemed a failure by the literary world he loved, ousted from friends, betrayed by others, alone with self-contempt.” But his genius produced Under the Volcano, which Richards calls “a map of our century’s soul.” And F. Scott Fitzgerald was braver and better than Hemingway. All three writers died by the age of fifty.

But tragedy is not a necessity for heroes, as Richards shows with Wayne Gretzky, “the antithesis of what a hockey player looked like,” yet a genius on the ice. In a “whisper,” he writes of Gretzky’s greatest moment: “It was when he sat alone on the bench after our loss to the Czechs in ’98. I realized, at that moment, five o’clock on that dreadful morning, that in some truly ultimate way, he had given us everything he ever had.”

The Gretzky essay is one of several that have poignancy and pith; they expand the book’s moral landscape. With empathy for strangers and outsiders, Richards attempts to figure out the world with these pieces. This aim is borne out by vignettes of desperate, solitary figures, including a stranded, drunken man whose car is in a ditch and who has lost new teeth. It is also the case with a lost friend, thrown from his car at three in the morning. While dying, he pleads with a young woman, “Just hold my hand, please hold my hand — and don’t let go.”

Richards argues that for all Canada’s championing of multiculturalism, there has been a long history of rancid class conflict and bias. He frequently defines himself in opposition to the country in general, his grievance being that it “has tried by its culture and much of its literature to silence most of what I care about.” Canada has been condescending or patronizing, when not simply dismissive or mocking of Maritimers and the working class. Leaving aside his own distaste for Quebec’s behaviour (created, he acknowledges, by historical injustice, but in many ways the attitude of “a self-traumatized, self-obsessed adolescent, trying to hide at least a little bit of racist acne”), Richards aims his choler squarely at the elites, especially the CBC and the intellectual class:

Canadians like me must agree with what others in urban media outlets promoted as Canada — and if we did not, we would never be as Canadian as they were. But the real secret was: even if we did agree, we would still have to apologize for who we were most of our lives. And I would not apologize or feel less than those who told me to, again.

He wrote that in 1998, and it is a sentiment that I happen to share. But the irony of sharing it with a writer who has since been honoured as a senator — an elite, if not decidedly effete position — is not lost on me.

Keith Garebian has just published his eleventh poetry collection, Three-Way Renegade, as well as a memoir, Pieces of Myself.