What exactly is Evie of the Deepthorn? This is the question posed on the book’s back cover. It’s the idea that follows the reader through three distinct but connected narratives. It’s a challenge that, even at the end of the novel, still percolates in the back of the mind.

Evie is, before anything else, the debut of André Babyn, a protegé of Miriam Toews. His first showing is an incredibly ambitious one. With multiple narrators and storylines, the book turns literary form on its head, filtering the story through several different structures, beginning with an introductory letter from the author himself. In constructing a narrative that loops back on — and even consumes — itself, Babyn has created something elusive that defies tidy characterization and even, in many respects, a review.

To the three protagonists, Evie of the Deepthorn is both a cultural artifact and a motivating force, something that inspires and drives them toward their interconnected goals. To Kent, a high school student who narrates the novel’s first section, it’s a cult-classic Canadian fantasy film about a young girl who travels through a forest on a quest to slay an ice queen. To Sarah, the hero of part 2, it’s a book she’s writing as an adolescent about a similar girl on a similar quest. To Reza, it’s a poem that gives him meaning as he travels to Durham, Ontario, to pay his respects to its long-gone creator. To all of them, Evie is a lens through which to process grief, a means of expression and growth.

So that’s Evie the cultural touchstone, but what of Babyn’s book? Like the works of art at its core, the novel is difficult to pin down. It’s at once a coming-of-age story, a cautionary tale of the dangers of nostalgia, and an ode to the vibrancy of interior thought and the power of culture. At its heart is a fantasy tale, a hero’s journey — Evie itself: the poem, movie, book, and character — that breathes life into the rest.

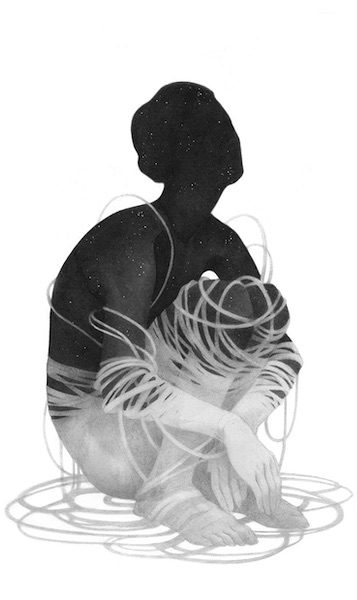

A narrative that loops back on itself.

Ashley Mackenzie

Kent is struggling to cope with the loss of his older brother, Jeff, an emotionally stunted high school dropout who used to withdraw into the card game Magic: The Gathering. The setting is Durham in the early 2000s, which in all its detail feels as though it’s rendered in technicolour. The suburban sprawl is at times depressingly modern and at others timelessly bleak: a town whose “great pride is in being accidentally named after a man who helped destroy French and Indigenous culture in the service of our British colonizers.” Tasked with creating a documentary for a school project, Kent grabs an old camcorder he finds in his attic and journeys forth. Inspired by the cult classic Evie of the Deepthorn, he seeks to make a movie that has something to say — about what, he’s not entirely certain. We follow him through the process of creation, watching as he comes to terms with the impossible task of growing up and away from old friends and old modes of thinking.

We join a similarly restless Sarah as she is writing her first novel, Evie of the Deepthorn: a fantasy epic that bears a striking resemblance to Kent’s cult film. She is lonely and acne-ridden, and her story, together with the hero at its core, becomes a means of interpreting her own troubles: her parents’ impending divorce —“You’re just broken, and in your heart you wish things were different”— and the awkward teenage years, when “there’s no triumph on the other side.” In the second half of her narrative, we catch up with her at age twenty-six: her father is dead, her mother remarried, and Sarah, her dreams of becoming a writer quickly crystallizing into failure, returns to Durham to house-sit with the family cat. As she processes her father’s death and her dissatisfaction with the shrinking parameters of her life, she finds herself travelling into Durham’s fading woods, where she encounters Kent, a former classmate turned best-selling poet. As Kent and Sarah draw closer, their narratives begin to curiously intermingle.

Finally there’s Reza, a young man reeling from a difficult breakup. He’s undertaken a pilgrimage to Durham, the home of the celebrated poet Kent Adler, whose seminal work, Evie of the Deepthorn, provides him comfort. It’s in this final section that Babyn reveals the novel’s underlying mystery: Kent is simultaneously a student who lived in Durham in the early 2000s and an acclaimed poet who died in 1976. So what, then, is the connection between the two Kents and the three protagonists?

This book made sense only upon a second reading — and, to borrow a phrase from Sarah, a reader should intend “both to believe it all and to catch them out, to escape into the fantasy, but also to destroy the illusion.” (That is to say: spoiler alert.) Sarah is the primary protagonist, who, with her literary ambitions and epic scope, draws on Kent’s poem to create her Evie story and then a version of the poet himself, interpreting the facts of his existence through her own cultural context (Law & Order, The Simpsons, Magic: The Gathering) to form a new character. Sarah’s version of the Kent we meet in part 1 of the novel becomes a “fanfic” take on the original. Babyn uses each of their narratives to consider the process of creation, examining form through Kent and characterization through Sarah. The characters all share a desire to edit their lives, but Sarah is the ultimate creator, and the only one able to enact change.

It’s an ambitious leap, but is it successful? The execution falls a touch short. Though there are winks and nods aplenty to Babyn’s sleight of hand, the literary device he relies on — Evie as the connecting, ever-changing work — is difficult to follow. Having to negotiate the shifting sands of perspective puts us on the back foot. The book’s sections are also uneven, the first two eclipsing the third. Reza’s part is half as long and his character far less developed — particularly as Sarah continues to appear in his narrative. His purpose remains unclear, beyond being the vehicle for the plot’s ultimate reveal.

In the end, while readers may question the destination, the journey is undeniably enjoyable. Babyn has a way with words: his description of a stack of burnt notebooks as “a pile of twisted and charred metal spirals, like wrecked strands of DNA” is evocative and haunting. The line about “kindness calcifying into a cold mask” on the faces of teachers who lose faith in their students captures the insecurity of rejection so fully. As an exercise in form, this book takes a unique approach to universal themes, rendering the struggles of adolescence, growth, and grief in poignant detail. In aiming not “to remake the entire world, just transform a little piece of it,” Babyn succeeds entirely.

Bryn Turnbull has a Globe and Mail bestseller with The Woman before Wallis: A Novel of Windsors, Vanderbilts, and Royal Scandal.