The corridors of academe are full of thoughtful people reflecting on essence and understanding. Depending on their own predispositions and the nature of the things they seek to comprehend, they differ in their disciplines or approaches. But the authors of two new books make a compelling case that if one hopes to understand the human condition, one’s place in the world, or who we are and how we have become part of a community, imagined or not, then no discipline is better than history.

Trilby Kent, for her part, was motivated to put pen to paper because history is a discipline in trouble. Very little is taught in our schools, and fewer and fewer university students are choosing the subject as their major. Where it does come up in the classroom, it is fragmented and chronologically disorganized. Historical studies have been eroded over the past several decades by an emphasis on teaching those skills necessary to cultivate “compliant and adaptable workers” for a neo-liberal market economy, as the education activist and former high school history teacher Bob Davis once put it. This system, according to Kent, who studied history at Oxford and social anthropology at the London School of Economics, encourages students to question everything but to know nothing.

Our neo-liberal world has collapsed the epistemological distinction between the economy and society. The rationality of the market is everywhere. It is no longer understood as one domain among many; rather, it has been redefined to encompass nearly every aspect of life. Within this environment, education has become a means to an end, rather than the end in and of itself. The contemporary focus on science, technology, engineering, and mathematics — or STEM — is supposed to secure students more financially rewarding jobs than lessons in history or the humanities ever could. “It’s STEM jobs that are hiring, we’re told,” Kent observes. “Historians make lattes.”

Why does the trouble with history matter? Kent argues throughout The Vanishing Past that it matters because a lack of historical knowledge disempowers us as individuals and weakens us as a community. “History doesn’t simply tell us how to be good citizens,” she writes. “It equips us with the knowledge we need to comprehend our world clearly, and the ability to analyze it accurately.” In an era of fake news, a deeper knowledge of the past creates a more nuanced sense of context and the ability to probe evidence.

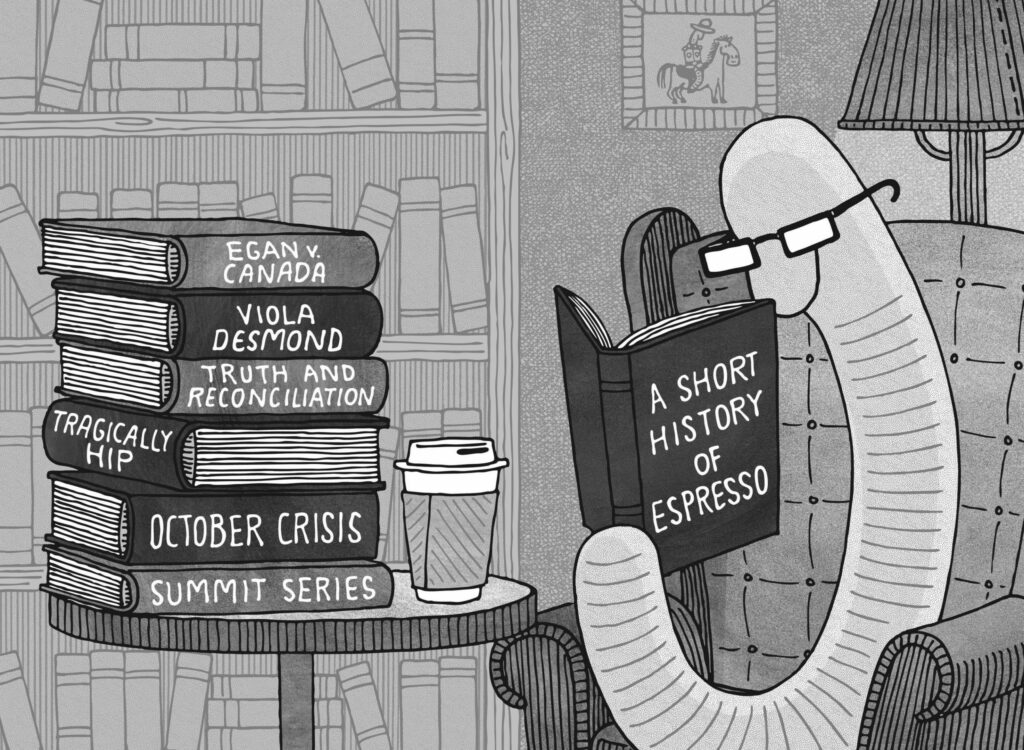

Worm your way into pivotal moments of the past.

Tom Chitty

But whose history should we be studying? A quarter of a century ago, Canadian scholars went to “war” over this question, with an older generation of (mostly male) political and economic historians arguing that a younger generation of social and cultural historians had “killed” Canadian history with their focus on such boring and meaningless matters as family, language, ethnicity, gender, class, and sexual orientation. Kent doesn’t seek to privilege one approach or another. Rather, she calls for a history that can be diverse, inclusive, layered, and complex — but, most important, for a history that is taught. “Subaltern histories, social histories, Black histories, Great Man histories, political histories, Marxist histories, Indigenous histories, women’s histories, LGBTQ2+ histories, Asian histories, Muslim histories, micro- and macro histories — none should be off-limits,” she maintains. Only by exposing students to the great historiographical controversies of the past and present can we equip them to evaluate different accounts of the same events. Indeed, to fully appreciate the vast arc of human interaction, engagement, conflict, cruelty, retribution, and reconciliation, society needs to acknowledge the good and the bad. After all, Kent points out, “few of the heroes we venerate for bringing about positive change in their time were without any moral stain.” In other words, we need to avoid monolithic interpretations of the past and instead situate events and ideas in their appropriate historical circumstances.

Like Trilby Kent, Aaron W. Hughes was motivated to write his latest book, 10 Days That Shaped Modern Canada, out of a passion for history and for the country in which he once lived. Hughes, who teaches at the University of Rochester, in New York, also believes chronological order is the best way to convey information, and here he presents a sequence of ten watershed moments.

Hughes does not pick his days at random. These are hinge points in the making of a modern state, one he sees as imperfect but improving — trending toward a more liberal and egalitarian society. Historical change so often moves at a glacial pace. But sometimes an event is so revolutionary that it touches everything around it, transforming countless social, economic, cultural, and political aspects of life. In this sense, each of Hughes’s days takes on “a much broader significance than was often apparent even on the day itself.”

Each chapter focuses on a single important date; Hughes describes the event and the historical circumstances that led up to it. While technically isolated from one another, these ten days, which span five decades, are intimately connected and interwoven. Hughes also makes intelligent connections between then and now: “These days thus create a whole that is much greater than the sum of their actual parts.” When understood both contextually and in terms of their causes and effects, they help to provide a portrait of how Canada came to be and how we as Canadians view both ourselves and our place in the world.

For Hughes, the history of modern Canada starts on October 13, 1970, the day Pierre Trudeau boldly stated, “Just watch me.” The prime minister had been asked by a reporter how far he would go in using the military to restore social stability during the October Crisis. Three days later, Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act, which had not previously been used in peacetime. The October Crisis brought to a boil the simmering tensions between the French- and English-speaking populations. Hughes rightly notes that the nationalist movement in Quebec never spoke with one voice: some separatists wanted peaceful negotiations, while others employed violence in pursuit of their goals. Furthermore, Indigenous leaders in the province tended not to support separatism. And while Trudeau’s action ultimately suppressed the unrest in Quebec, the underlying tensions continued to reverberate in the country at large.

In the years after the crisis, the defining debate was over the terms of sovereignty. When a second vote on whether Quebec should proclaim itself independent was held, First Nations were not consulted about the referendum or where they stood on separation. So, Hughes argues, the story of October 30, 1995, speaks to not only the rifts in Canadian society between French and English speakers but also the shameful historic treatment of Indigenous people.

If October 13, 1970, was one of Canada’s darkest days, then one of its brightest, Hughes suggests, was September 28, 1972. That is when 16 million Canadians tuned in for the final game of the Summit Series. With three-quarters of the population watching, the third period entered its last minute with the score 5–5. A tie would mean a win for the Soviets by virtue of their side having scored one goal more over the course of eight games. But with just thirty-four seconds left, Paul Henderson shovelled the puck into the net. When the final buzzer sounded, Canada had won the contest. “Canadians came together in a way they never had before and perhaps never will again,” Hughes writes. “If the country looked like it was going to unravel in the fall of 1970, the fall of 1972 saw Canadians come together in a celebration of their national sport and, by extension, their nation.” Thus, while the October Crisis had seen a terrorist organization almost rip Canada apart, the Summit Series represented a collective catharsis.

April 17, 1982, was also a momentous day. On that date, Pierre Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II signed into law the Constitution Act, 1982. While Hughes considers the day as one worth celebrating — because it has done so much to help “shape modern Canada”— the achievement was not without flaws. For one thing, as has been the case far too often, conversations leading up to the legislation’s ratification ignored the voices of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. Furthermore, because Quebec’s premier, René Lévesque, “was a proud Quebecer who sought to free the province from the economic, political, and cultural yoke of a federal regime that promised much, but delivered little,” his government refused to endorse either the patriation of the Constitution or the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In some ways, then, the day that was supposed to showcase national unity just as clearly exposed ongoing divisions.

Hughes similarly views the ratification of the Multiculturalism Act, on July 21, 1988, as a watershed moment. Like the Charter, the act established the legal principles whereby Canadians could flourish with a distinct vision of themselves and their place in the global order. As he notes, multiculturalism has resulted in one of the highest per capita immigration rates anywhere. But he does not ignore the policy’s detractors; in fact, he gives them a fair hearing. Nevertheless, the act has transformed Canada into what is arguably one of the world’s most culturally, religiously, and ethnically diverse nations. And Hughes sees that as something to celebrate.

All the days selected by Hughes serve as mirrors giving Canadians glimpses of themselves, but some days reflect an image that is much less attractive than others. A case in point: December 6, 1989, when twenty-five-year-old Marc Lépine entered a class at Montreal’s École Polytechnique armed with a semi-automatic rifle and hunting knife. A self-described “anti-feminist,” he killed fourteen women and injured fourteen others before committing suicide. It was the first large-scale massacre in modern Canadian history, and its legacy is manifold. For one thing, the day left Canadians aware of “the triangulation between misogynistic violence, gender stereotypes, and the political structures that make them possible.” In addition, it forced us to confront the gun question. And while we have been much more willing than our neighbours to the south to do something about such violence, the issue brought to the surface lasting tensions between rural and urban regions, as well as between east and west.

Hughes sees May 25, 1995, as another crucial turning point. On that day, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled on Egan v. Canada, establishing that sexual orientation constitutes a prohibited basis of discrimination under section 15 of the Charter. The decision — which actually went against James Egan and John Norris Nesbit, in their fight for spousal access to retirement benefits — set the stage for a series of rulings that made all couples, and by extension all Canadians, equal before the law. For Hughes, this is another bright spot in our history.

Some days are years in the making. One such day was June 2, 2015, when the executive summary of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report was released. Few Canadians would now argue with the conclusion that Indigenous people have been wronged in countless ways for centuries. But Hughes — like many others — is increasingly interested in why it took the government so long to acknowledge the mistreatment and the proper place of Indigenous people in the broader society.

Many of the days that Hughes examines involved Indigenous groups tangentially: their concerns were usually confined to the margins, with Indigenous people forced to play supporting roles in a never-ending drama between white anglophone and francophone Canadians. But that June day in 2015 put their points of view front and centre. Hughes, however, is not willing to state that this date will go down in history as a day of great reconciliation; that will be determined only with time. “June 2, 2015,” he writes, “is, at least at the moment, more about its potential than about what the events of the day have actually accomplished.”

The same cannot be said of August 20, 2016, when the Tragically Hip took to the stage for their final concert in their hometown of Kingston, Ontario. By the time the band played its encore, its legacy was firmly established. For Hughes, culture has the power to unite. As they did with the Summit Series forty-four years earlier, Canadians came together that night to celebrate one of their most treasured icons. The relationship between the Hip and the country “is, in the final analysis, part of the much larger narrative of how Canada perceives itself, often in the light of its unruly neighbour.” Canadians are constantly bombarded by cultural imports, but the Hip “offered an alternative.” Here was a band that was made in Canada, played in Canada, stayed in Canada. Hughes interprets the fact that these artists were adored by their fans as evidence “that Canada was in good shape and could, at long last, take comfort in its own cultural and artistic productions.”

The final date celebrated in this book is a little more amorphous than the others. In his last chapter, Hughes focuses on March 8, 2018, because it commemorates injustice and, hopefully, illuminates the path to a more just future. On that day, Viola Desmond’s portrait replaced Sir John A. Macdonald’s on the ten-dollar bill. A Black businesswoman and civil rights activist in Nova Scotia, Desmond faced discrimination and racism throughout her life, as Hughes recounts adeptly and concisely. The roots of anti-Black racism and systemic discrimination run deep. They are, as Desmond’s experiences in the first half of the twentieth century reveal, historically embedded in Canadian society, culture, and laws, and — perhaps most dangerously — in many shared attitudes. The new banknote was supposed to showcase the important but often unheralded role of women in Canada’s past, while simultaneously acknowledging the wrongs committed against visible minorities. March 8, 2018, then, is another watershed moment that represents “the culmination of injustice and the desire to move forward.”

10 Days That Shaped Modern Canada tells several striking stories. A very readable book, it offers some new and exciting interpretations of a number of old themes and topics. Not every reader will agree with the author’s point of view or his choice of days. But this is part of the volume’s charm. While, as Trilby Kent notes, it is all too common today to ignore history and downplay historical forces, the days highlighted by Aaron W. Hughes illustrate that in order to understand who we are as a national community, it is essential to be aware of where we came from. That is to say, it is important to be conscious of the ever-present past.

Matthew J. Bellamy is a historian at Carleton.

Related Letters and Responses

Joe Martin Toronto