In November 1966, Andy Warhol attended Truman Capote’s legendary Black and White Ball, at the Plaza Hotel in New York. He wore black tie, as the invitation requested, but he neglected an essential item. Though he left home in “some kind of electrified cow’s head,” a nod to his Castelli wallpaper, he arrived at the masquerade without a mask. As Blake Gopnik’s meticulous and compelling new biography shows, however, Warhol didn’t need one to be disguised.

Warhol was a fascinating mess of self-creation, as contrived as any of the elaborate confections worn by the hundreds of socialites at the Plaza that evening. In a way, his exposed face let people know that wearing a mask was redundant. As Gopnik suggests, this kind of observation, which many made at the time, is both overly simplistic and accurate. “The primary creation of Andy Warhol is Andy Warhol himself” begins to feel like an “empty cliché,” he writes. “Yet that conceit can’t quite count as a cliché, because it wasn’t just a notion dreamed up by writers to get a clever slant for their pieces. For some of the most daring and serious artists of Warhol’s era, an attempt to collapse art into life, and to make their lives count as art, had become a full-blown agenda.”

Warhol is over 900 pages. Considering that Churchill: Walking with Destiny, by Andrew Roberts, had to fit in two world wars and is only 200 pages longer, Gopnik’s thoroughness could have been numbing. But his ability to animate passages with pithy observations and salacious tidbits makes this an enjoyable read, like many of his pieces in the Globe and Mail, the Washington Post, and the New York Times over the years. The book’s format is helpful too: fifty bite-sized chapters, each starting with a few teaser subtitles whose meanings are revealed as you progress.

Every chapter is also enlivened by Andyisms. “Isn’t the art scene today revolting?” he once asked Cecil Beaton, the British fashion photographer. “I wish I could find a way of making it worse.” But as far as anyone can tell, his most beloved quote —“In the future everybody will be world famous for fifteen minutes”— isn’t actually his. That one, Gopnik explains, “owes its spread almost entirely to its place in the Moderna Museet catalog.” There’s little evidence to suggest that Warhol ever used the line, at least not before “everyone was already quoting it back to him as his best-known bon mot. Like almost all of Warhol’s mots, it’s not clear it’s even that bon, especially given the vastly different ways it’s been read over the decades.”

Sign up for another fifteen minutes.

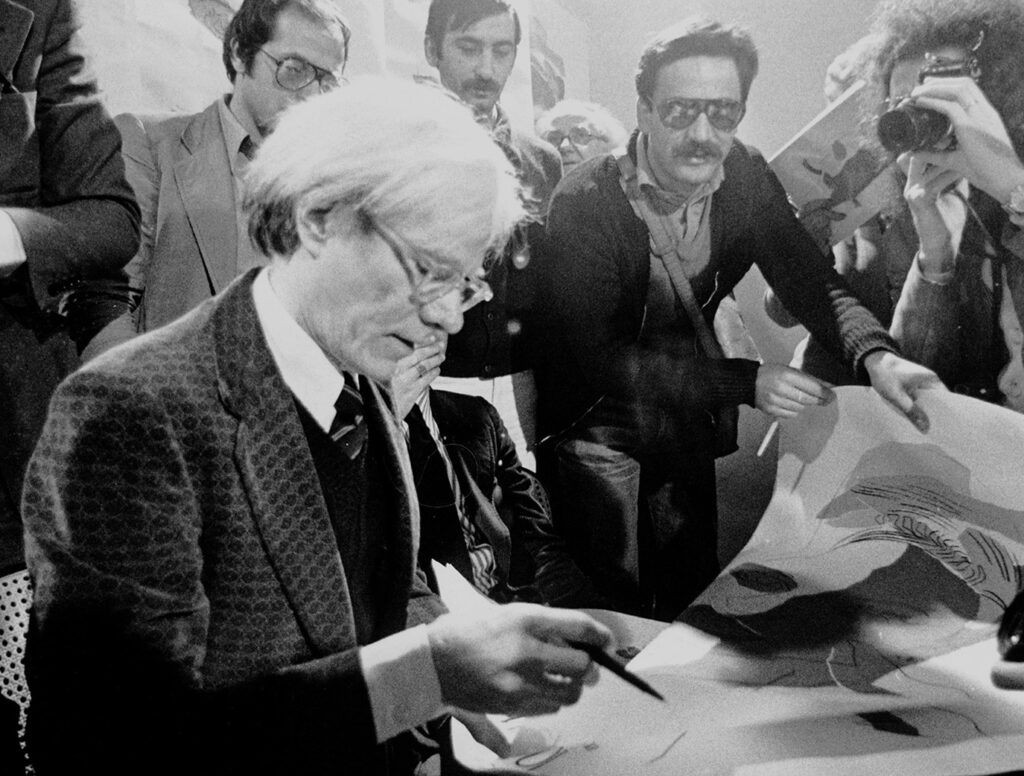

Mark; Alamy Stock Photo

Gopnik shows how Warhol was calculating and intellectual, the antithesis of naïveté and inarticulateness, the core attributes of his brand. In other words, Warhol was smart and hid his erudition; he was a brilliant actor playing a role, not an idiot savant. “It’s important to recognize just how carefully Warhol constructed his public persona,” Gopnik writes. And that construction caught many contemporaries off guard:

A critic underlined the difference between the cultivated media image of Warhol as “free, eccentric, cool, drug oriented and certainly perverted” and the reality of his existence at home with his churchgoing mother, where he avoided “excess of any kind.” Another writer admitted to being surprised by what he found when he finally got to meet Warhol in the flesh. “Meeting you is rather startling,” he said to the master. “I don’t know what I expected you to be. Something sort of whispy and otherworldly, I guess, after all I’ve read. But you seem remarkably down to earth.”

Even if he avoided “excess” around his mother, Warhol did indeed drink a lot and do drugs, although not in the quantities that destroyed Edie Sedgwick, briefly a Warhol superstar. In fact, given his socializing and the amount of booze and drugs he consumed, it’s surprising that Warhol ever had time to work or was even capable of getting to the Factory.

So there’s confusion between the carefully crafted personas and who Warhol actually was. But to make it even more mixed up, every observer seemed to have a different perception of both. “Was his art a put‑on,” Gopnik asks, “or was the put‑on his art? Was he himself a joke or a genius, a radical or a social climber?” There are no easy answers, except that Warhol himself would have always answered just “Yes.”

Did Warhol allow intuition to guide him, as he shrewdly rationalized where it got him? Did he constantly survey the landscape for the next source of inspiration? Gopnik describes Warhol as “the world’s greatest sponge,” who could in fact absorb and rationalize. But perhaps it was better to just let others explain the life and work for him. That an artist could be a brand wasn’t a new concept — Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali were there already, or for that matter Leonardo da Vinci. But that an artist’s brand could be so independent of the artist’s personality — or even his art — is an achievement that Warhol pioneered.

A biographer’s task is daunting, especially when a personal history progresses without revealing too much character. In that case, the subject’s veneer becomes the essence of the unfolding life. Andy Warhol compulsively manipulated his image. He claimed to be born variously in 1929, 1930, and 1933, and when quizzed about his changing stories he’d say, “I make it all up different every time I’m asked.” After seven years of research and over 250 interviews, Blake Gopnik surely has his facts correct, although this seems to matter less than it should. Gopnik’s biography blends his exacting chronology with Warhol’s exaggerations and pronouncements; with descriptions of the stuff he made, sold, hoarded, or coveted; and with the conflicting impressions of intimates and strangers. The resulting mélange is a contradictory one, but then that might be what Gopnik is telling us is the authentic Warhol.

Warhol is far more entertaining than any of Warhol’s 650 or so movies, such as Sleep (five hours of a man dozing) and Empire (a notorious eight hours of black and white slow-motion footage of the unchanging Empire State Building). Yet the book is reminiscent of those films because it feels as if the ordinary and the exceptional are given similar weight. An uneventful road trip across the United States, for example, gets as much space as Valerie Solanas, the radical feminist and former acolyte who shot Warhol in 1968.

Despite Warhol’s lifelong obsession with Hollywood and its stars, his own movies are mostly unglamorous — even when they strive to dazzle. The banality of experience is more often the point than a dramatic or coherent narrative. As his story moves from the birth of Andrew Warhol in 1928 in Pittsburgh, to his studies in art at the Carnegie Institute and graduation in 1949, to his work as a commercial illustrator in 1950s New York, it gains an unexpected hypnotic momentum, even though so much is about a quite ordinary day-to-day existence. It’s as if Gopnik opened one of Warhol’s time capsules — 300,000 objects in cardboard boxes that he assembled during the last thirteen years of his life — and set out to describe the contents, one object at a time, in a thoughtful if not reverential manner.

Something that doesn’t figure prominently in most writings about Warhol, or even in his own diaries, is his homosexuality. Warhol was conscious of his queer identity in elementary school and made no apologies for it. He flaunted his interest in girlie stuff instead of hiding it. He was not asexual, as some thought or wanted him to be (especially after his death, when they tried to sanitize his image). He was frequently portrayed as a voyeur or as someone who had sex vicariously through his superstars. Others said that he was a closeted poseur, who let people believe Edie Sedgwick was his girlfriend and who focused on the straight, white rich world.

But Warhol was most definitely gay. He seemed to have a new boyfriend or crush for every phase in his life, and there were many of both. Although Warhol’s appearance, hygiene, and abilities as a lover garnered a multitude of less than flattering descriptions — and though Warhol himself thought sex was “messy and distasteful”— there was plenty of it.

Famously, Warhol was a habitué of Studio 54, and his constant presence there took a toll on his personal life. In a poignant note, Jed Johnson, one of his last boyfriends, said it made their relationship impossible. Warhol was greatly influenced by such gay heroes as Jean Cocteau, the perverse trickster, and Jean Genet, the beautiful outlaw, while his network of gay friends, including the likes of Truman Capote, introduced him to dealers, curators, and potential patrons and kept him at the centre of an art world web.

Warhol’s sexuality is central to both the creation of his personas and his emergence as a pop artist. In 1965, Gopnik explains, the New York Times “at last decided to educate its middlebrow readers on what it called the ‘bewildering’ concept of camp.” And where else to find the bizarre, unnatural, artificial, and outrageous than among gay men, whom American society saw as inevitably copping to such descriptors?

It’s not surprising that being gay in the mid-twentieth century would spur a self-consciousness about identity. For Warhol, it proved the training ground for his eventual fabrication of a saleable image. “If the avant-garde’s interest in self-creation added prestige to Warhol’s constructed persona,” Gopnik writes, “it had deeper roots in who and how he had always been.” He continues:

There was no way to be homosexual in postwar America without self-consciously playing a role, because the culture didn’t leave you feeling that there was any “natural” self you could inhabit. You were either playing at being straight to hide being gay, or you were figuring out how to be gay by adopting one of the models that had worked for others before you. In the case of Warhol and many of his friends, that involved going camp.

It was this camp sensibility that they combined with the attitudes of Duchamp, other Dadaists, and assorted radicals. It fuelled the pop art transformation of the low — from comic books to everyday consumer goods — into the high.

Abstract expressionism was the opposite of pop. The lofty intent of its practitioners — the über-males like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning — contrasted with the goals of the pop artists, who nodded to the ordinary and lacked painterly concerns. If ab‑ex was a macho club, gay artists felt they didn’t fit in. Warhol and his friends, such as Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Larry Rivers, and Roy Lichtenstein, were the kind of guys who had avoided the gym in school and who flaunted their queerness. And they were on a collision course with the hard-drinking jocks. (“One childhood friend remembered [Warhol] being just as interested in having fun as any other neighborhood kid — but also how he would collapse at the slightest contact during games of street hockey.”) Ab‑exers painted big and bold and made brash statements. The sissies camped it up, made subversive statements, and were not overtly reverential. They had embraced taboos and lived pop as camp long before they created it as art.

Out of a “desire to shock,” they embraced the taboo of capitalist consumerism. Gopnik quotes Lichtenstein as saying, “It was hard to get a painting that was despicable enough so that no one would hang it — everybody was hanging everything.” Yet there was something people almost universally hated: commercial art. “So that, of course, is where he and Warhol had headed.”

Warhol began with commercial work and always valued the commercial production of art — fine or otherwise. The abstract expressionists weren’t keen on the interloping window dressers, like Johns and Warhol, who moved their pieces from department stores and retail displays to the rarefied world of galleries and patronage. It was his camp sensibility, his veneration of commercial success, and his distaste for the male-dominated world of ab‑ex that propelled Warhol toward his breakthrough pop moment: his Campbell’s Soup paintings.

New York’s East Side gay crowd immediately recognized those paintings as a camp joke. At one point, Warhol even drew the feet of a friend “pressed against a Campbell’s Soup tin on which only the letters C-A-M-P were left visible.” But maybe the joke, too, was affected. Warhol supposedly explained the paintings to a friend as “the synthesis of nothingness.” They were “a pure, dumb, Duchampian gesture,” Gopnik writes, “a mere ‘nothing,’ chosen almost at random — because they were there, the first thing that came to hand.”

Gopnik then describes Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup “eureka moment” as among “the greatest in the history of art.” Here, Gopnik’s reading raises eyebrows, not because of his perception of the moment but because of the hyperbole he links to it. He makes this surprising claim approximately 200 pages into the book but then keeps his boosterism mostly in check until the last page. At that point, he goes even further:

The critical skepticism that Warhol lived with has evaporated in the years since his death. It’s looking more and more like Warhol has overtaken Picasso as the most important and influential artist of the twentieth century. Or at least the two of them share a spot on the top peak of Parnassus, beside Michelangelo and Rembrandt and their fellow geniuses.

It’s an occupational hazard for a biographer to fall in love with his or her subject, and after seven years of cohabitation with Warhol, it’s not surprising that Gopnik is enamoured. If he had made the above statement at the outset, he would have turned off many readers. And given all of the failures, obfuscations, bad reviews, negative perceptions, insecurities, and rejections that Gopnik details throughout the book, the praise feels like an unconvincing non sequitur.

Although Warhol makes most of the top-ten lists of influential twentieth-century artists, there’s no consensus that he is the greatest of the lot — certainly not ahead of Picasso, if it were a horse race and individuals could be ranked in this way. The most negative critics typify Warhol as having created well-known, high-status products that a brand-obsessed art world can readily consume. His oeuvre is not good or great, but today it’s easily identifiable as luxe and this is why it succeeds. (Wouldn’t Andy be pleased?) Moreover, Warhol doesn’t even dominate contemporary references to pop art; he’s generally viewed as one of several key participants. Surely, many will laugh out loud when they see Warhol’s worthiness associated with the genius of Michelangelo and Rembrandt.

Yes, Warhol’s work continues to sell for stratospheric prices, his brand endures as the coolest of the avant-garde (while there was an avant-garde), and the social history of the art world and New York will forever identify him as a celebrity. But will Gopnik still insist Warhol is astride Parnassus a decade from now? Could Duchamp push his acolyte Andy off the mountain? Or maybe Gerhard Richter will be unmasked as the greatest? If not, perhaps he’ll have his own 900-page biography to make the case that he should be.

Kelvin Browne wrote Bold Visions: The Architecture of the Royal Ontario Museum.