My friend pointed out Marshall McLuhan’s house and said that if we waited long enough, we might see him. It was the early 1970s, and I was visiting Wychwood Park, a bucolic enclave in midtown Toronto. “Who’s he?” I asked, getting an incredulous stare in return. “He’s very famous. You know: the medium is the message.” I couldn’t fathom why this University of Toronto English professor was a star, and my friend couldn’t really explain what his celebrated aphorism meant, other than that it was “genius.” However, he was certain that McLuhan was worth stalking.

Unlike Northrop Frye, another U of T professor with an international reputation, Marshall McLuhan didn’t earn his fame primarily through academic or highbrow preoccupations. Instead, he dealt with what most of us encountered daily: the media. (And, unlike McLuhan, Frye never had a cameo in a Woody Allen film.) But after a period of renown, McLuhan’s prominence declined. He was television’s oracle, and then TV wasn’t new or mysterious anymore. He died in 1980, well before the internet became ubiquitous. When that happened, more than a decade later, McLuhan’s concept of the global village felt prescient, and he was rehabilitated and quoted with abandon — often by new-found acolytes who, like my university friend, didn’t always understand what they were repeating.

Understood or not, McLuhan’s work was influential in its time, and with Distant Early Warning, Alex Kitnick shows how it spoke to numerous artists of the avant-garde. These artists may already have been aware, even if not consciously, that twentieth-century media consumption was leading to a significant cultural shift, but McLuhan’s analysis helped give shape to their intuitions. That’s why, Kitnick argues, McLuhan should be considered more relevant today than he is: not because of his role in nascent media studies but because he was a bona fide player in the art world.

Kitnick, who teaches art history and visual culture at Bard College, in New York, describes his book as an introduction to “McLuhan’s theory of art” and an attempt to position him “alongside contemporary artistic developments rather than simply as an inspiration behind them.” In doing so, Kitnick wants “to reimagine the relationship between theory and practice, criticism and art.” By considering “concrete points of contact,” each chapter puts McLuhan into context with individual artists, specifically those working in the “Anglo-American tradition from which McLuhan sprang and the North American reality with which he wrestled.” This is a good way to revisit McLuhan, particularly as his work is too often reduced to enigmatic bons mots. Despite Kitnick’s academic tone, he makes a compelling case, and the artists he touches upon were indeed aware of and affected by McLuhan, although one wonders if they actually slogged through his complex books or instead came to his theories via cultural osmosis (as many did with the trendy isms of Roland Barthes).

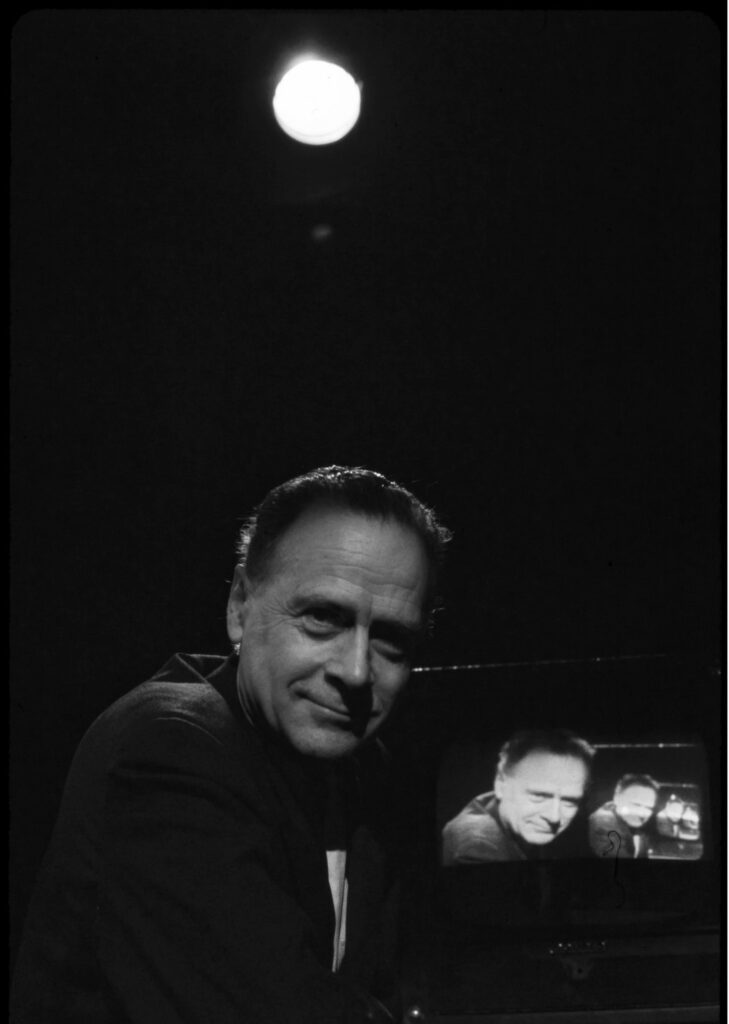

Portraits of an artist?

Bernard Gotfryd, 1967; Library of Congress

The journey to understand McLuhan as a “theorist of art” begins with Marcel Duchamp. Kitnick draws connections between two of the artist’s seminal early works, Nude Descending a Staircase and The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, and McLuhan’s 1951 book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man. “In retrospect,” Kitnick writes, “it is easy to see the proto-Pop tendencies at work in The Mechanical Bride, such as the emphasis on appropriation and the ambivalence about mass culture.”

Although most of the artists discussed didn’t overtly express links to McLuhan’s work, Kitnick argues he was present nonetheless. “McLuhan had a novel take on Pop art. While many saw it as a study of the popular image, he considered it a form of environmental research.” Often, the creator and the professor reacted to the same thing but from very different vantage points; to some degree, each missed a lot of what the other was doing.

McLuhan’s connection to Andy Warhol, however, went beyond theories of art. In popular culture, McLuhan was the philosophical or sociological interpreter of the world, and Warhol was the artist who transformed its camp into commerce. As celebrities, they were both well known for being well known, and for oft-repeated sound bites (some of which they probably never said). Despite being in the public eye and enjoying the spotlight, both remained unfathomable — personas, not real people. McLuhan played the sage academic, with a tweed suit and a pipe, while Warhol epitomized the avant-garde, with his black leather jacket, sunglasses, and platinum wigs. Each fashioned himself as a cool, sought-after brand.

Both were also devout Catholics. McLuhan taught at St. Michael’s College, at the University of Toronto, and attended its church, St. Basil’s, without fail. Warhol was equally committed in his faith, although he was much more discreet about letting others see the religious aspect of his life. Some have speculated that the two men even shared a horror of consumerism (although Andy was a notorious hoarder) and that this distaste helped drive their obsessions with the commodification of life. Materialism had become the new religion — and that’s not a concept a good Catholic can easily accept.

Despite their similarities, Kitnick writes, “Warhol was underwhelmed when he met McLuhan,” in April 1973. He quotes Warhol’s confidant Bob Colacello, who recalled, “Andy passed up dinner with Joan Crawford for dinner with Marshall McLuhan, and was furious with himself for making the wrong choice.”

McLuhan and General Idea, a collective in Toronto, were also on the same wavelength. AA Bronson, Felix Partz, and Jorge Zontal had come together in the late 1960s, “in a maelstrom of mail art and media frenzy, and, in many ways, they portrayed themselves as McLuhan’s children — analyzing, critiquing, and mimicking the media, though not seeking to overthrow it.” Of course, those weren’t the artists’ real names: making them up was part of their savvy shift to media content, a very McLuhanesque approach to art.

Bronson, Partz, and Zontal “operated like a collective,” but Kitnick points out that they “considered themselves more like a band. They were artists but not quite.” Like McLuhan and Warhol, they transformed themselves into a marketable label. Their various enterprises included the Miss General Idea Pageant and a project where they remade Robert Indiana’s LOVE icon by substituting the acronym AIDS. In a series of “infected” Mondrian paintings, they contaminated reproductions of the Dutch painter’s familiar work with green, a colour he never used. They also mounted large installations of football-sized AZT capsules. These artists were definitely provocateurs but ones who used the media to infiltrate and subvert rather than openly confront.

“Think of them as undiscovered pop stars who play the media instead of guitars,” Philip Marchand wrote of General Idea in a Toronto Life profile published in 1975 (fourteen years before he published a biography of McLuhan). Their most obvious embodiment of a McLuhan-inflected sensibility was Test Tube, from 1979, which took the form of a talk show. With a set that resembled a test pattern — they called it the Colour Bar Lounge — theirs was a television show that aspired to be a television show. They even included fake commercials between segments.

While Kitnick sees Test Tube as General Idea’s attempt to “figure out what artists can do with television,” I would argue that the three men already knew what artists could do with it — just as they already knew what artists could do with conventional print media. Consider, for instance, their take on Life, where they rearranged the magazine’s iconic logo to spell File. Their bait was the safe and familiar packaging, and the switch was an interior that presented an alternative world view, one that Henry Luce and his staid Middle America readers deliberately eschewed.

Distant Early Warning leaves one wondering what Marshall McLuhan would have thought about today’s media landscape — where people confuse real relationships with virtual ones, where screens meant to enhance the world actually distort ways of experiencing it — and how artists like General Idea might have subverted it. The internet hasn’t spawned a global village with shared values but has instead encouraged tribalism and fragmentation. “While the first generation of Internet artists considered cyberspace a free frontier,” Kitnick writes near the end, “others understood that the Web’s military origins would lead to new methods of corporate domination.” At this point, though, corporate misuse of the media probably doesn’t top the list of cyberspace misdemeanours, which have come to include ransomware, foreign attacks on democracy, hate campaigns that censure without due process when there’s a hint of impropriety, and cancelling those who are insufficiently woke or who did something stupid in their youth. Could McLuhan and his contemporaries ever have envisioned the coercion possible via the internet, now that the media is the mob?

Perhaps our current societal upheaval will look quaint in the rear‑view mirror, not unlike how McLuhan’s sense of the profound impact of the media strikes us today. But maybe it’s best to think of what McLuhan and his avant-garde contemporaries saw as just the head of some curious creature — new, strange, clearly malleable. Less than thirty years later, as the beast emerges further into the light, it’s obviously monstrous and untameable. And if we wait long enough, we’ll see there’s even more to come.

Kelvin Browne, recently left the contemporary art world to sail in Chester, Nova Scotia.