The first time a cop car stopped me, I was living near York University. As I jogged down Gosford Boulevard, two police officers pulled alongside to “have a chat,” because I was clearly “new to the area.” Years later I moved to Summerhill, where I’d run along the quiet, lush streets of midtown Toronto. One of my favourite routes brought me from Yonge Street to Avenue Road, where I tackled that infamous uphill stretch along De La Salle College. One day, a woman flagged me down from her porch, asking where I lived and why I ran past her house so often. She wasn’t asking so she could welcome me to the neighbourhood.

In 2018, around this time of year, I was in great shape and training for a half-marathon. On a lunchtime run, with my shirt off on an extremely hot day, I passed a construction site. Waiting for a light to change, I heard some yelling. I looked around and caught several not-so-welcoming gestures aimed my way. Apparently, running without a shirt is one of the many things “we” do thinking we’re tough. But the construction guys reminded me that “we” aren’t tough at all — we’re just a bunch of slaves who ended up here. “Put your fucking shirt on,” one yelled as another reminded me this wasn’t Caribana. I’m of Ugandan and Burkinabe descent, but, hey, we’re all the same, right?

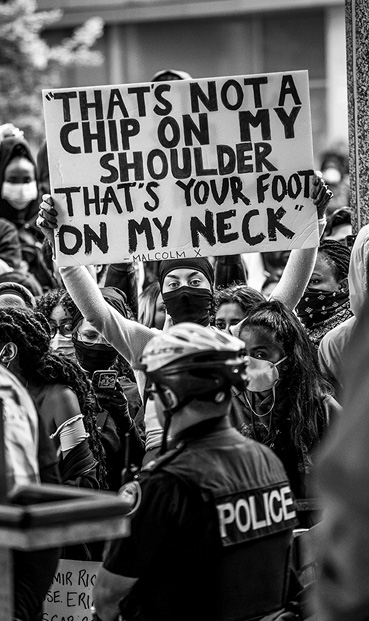

A sign of the times.

Bryan Dickie

Running is sacred. It’s the one physical activity almost every able-bodied person can do to celebrate our shared humanity. It’s pure, and has given me incredible joy. But on May 8, I texted the artist Bank Moody: “How are we supposed to feel free when the simplest expression of freedom costs us our lives?” We had heard the news of Ahmaud Arbery, whose brutal murder and its subsequent cover-up in Georgia had finally come to light. I couldn’t quite summarize how tired, angry, and exasperated I felt. Not only about Arbery and the plight of black men in America, but also about the naive perception of race relations here. This story hit different for me: that runner could easily have been me.

As I have done hundreds of times, on sunny and snowy days alike, Arbery went out for a jog on February 23, in a community not far from his mother’s home. As he made his way down an empty road, he was chased, cut off, and confronted by two armed white men in a pickup; a third man followed close behind, filming the scene on a cellphone. Moments later, the former star athlete was dead.

Arbery was twenty-five. He was unarmed and wearing a white T‑shirt in broad daylight. Allegedly, he matched the description of a local trespasser. But his real crime was running while black — one of the many transgressions in America that white men with guns consider to be punishable by death. This is just more evidence of how the “social contract” doesn’t apply equally. From runners to birdwatchers, people of colour don’t get to follow the rules that white people do. Instead, we’re governed by what the Jamaican philosopher Charles W. Mills called the “racial contract”— a set of formal and informal dos and don’ts that perpetuate subjugation, discrimination, inequality, and oppression.

Racism is a global problem, and Canada is far from immune, as a United Nations panel of experts reported in 2017. But the racial contract does operate differently here. When I landed at Toronto Pearson seventeen years ago, I knew that my experience wouldn’t be perfect, but I knew it would be different than if I were south of the border. And though running while black has not cost me my life, I can’t say that I ever live carefree. To be a black person, and a runner at that, is to be on constant alert, acutely aware of your surroundings and how you are perceived.

Even in the rain or the snow, I always run along certain streets with my hood down, so as to look non-threatening — so it’s obvious that I have nothing to hide. I always remove my earbuds when running through specific areas, so I can hear if I’m being yelled at or if anyone tries to pull up on me. Over the years, others have shared similar experiences and practices with me. And I am speaking only about running here; our caution must extend well into other parts of our lives, for own protection and preservation.

Running is how I discover cities all over the world: I lace up, point myself toward the landmarks, and get moving. I travel everywhere with a pair of running shoes. But I also understand what I am allowed to do — and not allowed to do — as a six-foot-four black man who weighs 215 pounds. I know how the rules apply to me, because to many eyes, I am an all-powerful threat that requires extreme force to confront, subdue, and deter.

In that sense, I could also have easily been George Floyd, killed on May 25 while handcuffed on the ground and pleading for his life — with a white Minneapolis police officer’s knee pressing down on his neck while others stood idly by. The forty-six-year-old purportedly resisted arrest, a claim supported by no eyewitness accounts. What the evidence does show is a supposed custodian of the peace exerting extreme force and violence against an unarmed, shackled, and defenceless large black male. “I can’t breathe,” words we’ve heard too many times, are now among the last words of a man who had moved to a new city, hoping to live a better life.

I have come back alive from every run, and I am grateful that our gun laws are stricter than those in the U.S. But racism is also found in the things one does and says, in public and private. It is the conditions, mentalities, and statements that guide and fuel ignorance, bigotry, and systemic discrimination. While it may look and feel different here, while it may take a more passive and less violent form, while it may be a taboo topic, racism is very much alive and pervasive. It is not confined to a few isolated incidents or to the few bad apples that people often try to dismiss. Denialism is as dangerous as apathy.

Canadians who are appalled and furious at the fate met by Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, and countless others have an opportunity to influence how we experience race dynamics here. We all can work toward equal access to resources and opportunities, and against the mental, physical, and social discrimination that disenfranchises and marginalizes us people of colour.

At its best, running is a microcosm of what equality might look like — a pure and beautiful act that can unify us all. Whether or not you run, take action against racism and educate yourself and others, starting with your family, your friends, your neighbours. Change starts with us all: how we speak up, how we protect, how we advocate, and how we stand with each other. And then, some day, maybe we can outrun the type of racism and bigotry that leads to so much unthinkable and unbearable tragedy.

Mark Nkalubo Nabeta is a son, brother, and freelance brand strategist in Toronto.