Our consumer-driven society has vulgarized the terms “curator” and “curating.” It seems as if almost anyone with an Instagram account can be a curator and that just about anything can be curated. As Jason Farago has pointed out in The New York Review of Books, restaurants today sell “curated salads,” home goods stores peddle “carefully curated sheets,” and daycare centres offer “curated care.” There are legions of curated wines, curated dating apps, curated newsletters, curated books, curated audiences. And before the pandemic forced Heathrow’s Terminal 3 to close, well-heeled passengers could enjoy curated hamburgers at the Curator.

It wasn’t always so. In Roman times, curators were bureaucrats or priests who managed regions or parishes. According to experts such as David Balzer, who published Curationism: How Curating Took over the Art World and Everything Else in 2014, the term “curating” entered the art world in the eighteenth century, usually to describe a private collector of unique curiosities. Initially, curators were passive caretakers of objects. They turned professional only once it became common for museums, like the Louvre and the Hermitage, to publicly display their material wealth. Curators developed an even more active and self-determined role in the late nineteenth century, when avant-garde art, with its abstractions that challenged ideological and commercial concepts, required experts who could help others make sense of the new forms. By the 1960s and ’70s, curators were full-time connoisseurs, working to secure, organize, and landscape their fields of expertise. With complex exhibitions, they transformed curating into a craft of its own. “In fits and starts,” Farago wrote in 2019, “the professional curator arrogated responsibilities once held by the artist, the collector, the historian, or indeed the critic.”

Well respected in the Canadian museum world, Rosalind Pepall believes that “a curator’s tastes and passions” contribute to an institution’s “permanent fabric.” As she explains in the preface to her fascinating new book, Talking to a Portrait, “Working behind the scenes, art curators select acquisitions, carry out research, install collections, court donors and interpret art, giving it meaning through exhibitions and publications.”

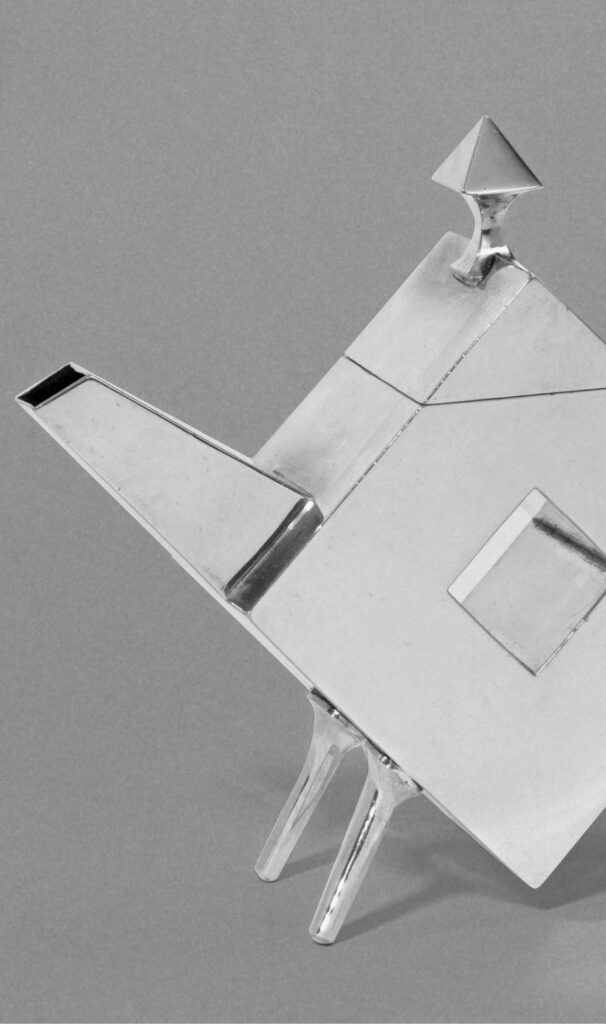

The vividness of a modern teapot.

Christopher Dresser, 1879; Metalwork Collection; Victoria and Albert Museum

Recently retired, Pepall fell into her profession “by happenstance” in the 1970s. A friend told her the Royal Ontario Museum’s European Department had an opening , and she accepted the “lowly position” because she was a twenty-three-year-old university graduate without a job. The ROM’s exhibition galleries with their wooden and glass cases were enticing , as were the “musty period rooms with their Georgian table settings, French salon chandeliers, heavily carved Elizabethan furniture and portraits of bewigged patricians.” Pepall was “smitten by this ‘old world’ ” in downtown Toronto, even before she fully understood it. One day, noticing that the director of her department sat “at an antique desk in a dingy, gloomy room full of dark bookcases, dark paintings and cracks in the wall,” she asked why he didn’t brighten up the office a bit with a bit of cheerful paint. “Oh, no, Rosalind,” he replied with a grin. “We must look poor and shabby, otherwise my visitors will think we don’t need any funding.” Such anecdotes add to the delight of the read.

Talking to a Portrait focuses on the curator’s active function in manifold ways, combining historical background with anecdotal foreground, biography, and aesthetic analysis in a manner that avoids the dryly technical and offers rich insights. Pepall left the ROM in 1978 to take a job with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, in her hometown. When she served as the curator of Canadian art, she would admire “the luminosity of an Ozias Leduc painting , the rolling hills of an A. Y. Jackson Quebec landscape, or Jean-Paul Riopelle’s Vent traversier, in which a violent breeze seemed to have whirled the rich reds, greens and yellows into a glorious expansion of colour across the canvas.” Later, as senior curator of decorative arts, she would wander through the storage rooms to examine “the simple beauty of Jean Puiforcat’s silver soup tureen, the playfulness of Carlo Bugatti’s armchair, or the Surrealist motifs by Jean-Paul Mousseau painted on a skirt that once swirled with its wearer on a discothèque floor.” From first to last, her fifteen chapters are full of lively stories about such things as oil portraits, a wilderness explorer’s sketchbook, Japanese kogos, and a beautiful private oratory.

Pepall’s professional enthusiasm is palpable as she recalls those early days at the Museum of Fine Arts on Sherbrooke Street:

Sometimes, instead of taking the employees’ back door, I would use the main entrance doors, passing through the four giant marble columns hewn from a Vermont quarry, each one cut from a single piece of marble. The lustre of white marble was carried over into the entrance hall, where I would continue up the stately staircase (its bronze railing copied from Paris’s Petit Palais) and arrive at the exhibition galleries, laid out like a European palace in enfilade.

The veritable mini-documentary is enlivened by sensory details and ends with a technical word that conveys a precise geometrical vista. Incisive thinking like this recurs throughout the book.

In the tradition of all first-rate curators, Pepall spends time pondering a work of art: “Who created it? When was it made and where? Why this style? The answers tumble forth, and they have taken me on journeys of discovery to Saint Petersburg , New York, London, Paris, the Barren Lands of the Canadian North and the canals of Venice.” It’s by asking and answering such questions that a curator contributes to the “permanent fabric of the institution.”

Putting aside the flawed title essay — an anticlimactic tale in which an old widow who owns an enigmatically cool portrait by Christian Schad frequently speaks to the painting like a cherished companion — Pepall’s writing is generally well wrought and opens up many areas of inquiry. Her first tale is in many ways a response to a question once posed to her: “Has a painting ever brought you to tears?” She carries us back to spring 2003 and a near-empty room in Ottawa, where she saw Ludivine. In that 1930 portrait by Edwin Holgate, a fifteen-year-old girl is numbed by grief and the burden of new responsibilities after the recent loss of her mother. Pepall delays her comments on the painting till after a brief biography of the Montreal artist, stressing his importance and how he differed from the contemporaneous Group of Seven.

Only then does she focus on the colours, textures, angle of light, and overall composition of Ludivine to reach its distinctive essence:

Holgate places Ludivine in a rigid, frontal position, hands tightly clenched in her lap, the muscles of her neck taut. She leans to one side, as if shying away from the bright source of light on her left. Even the collar of her dress has shifted off-centre. All attention is directed to her facial expression and her striking eyes, which stare out directly at the viewer. Her gaze holds our gaze. Her hair, like her dress, is black, a long strand curling into her cheek. The warm hue of her skin softens the darkness and glows through the muslin of her sleeves, as if to say, “I am very much alive.” The aquamarine background and vivid green of the sofa with its sharp-edged lines increase the emotional tension of the painting.

This is not simply good art criticism; it is perception linked to passion, where the viewer is connected emotionally to a subject who remains humanized despite the skillful artifice. But the essay does not end here.

Pepall continues her story of Ludivine with how A. Y. Jackson encouraged Vincent and Alice Massey to acquire it in 1930, for $350; later the Masseys donated it to the National Gallery. She then moves beyond the painting to Natashquan, Quebec, the Côte-Nord fishing village where Holgate rented a house from his model’s grandfather, and where Pepall herself visits decades later. In a dramatic moment, a distant relative of the girl shows Pepall a photograph: “There she was, Ludivine, whose youthful face Holgate had made eternal. She had grown old, a little plump, her short greyish hair held in a tight permanent. But there, unchanged, were those astonishing jet-black eyes, which set the photo ablaze.”

Cinematic vividness is present throughout Talking to a Portrait, especially in the chapters on the impulsive, outspoken, tart painter Jori Smith (whose 1935 portrait Rose Fortin also shows a solemn child, gazing at the viewer “with dark, doleful eyes”); on Christian Schad’s glitteringly decadent Baroness Vera Wassilko; on the English designer Christopher Dresser’s radically modern silver teapot; on Louis Tiffany’s signature glasswork; and on C. P. Petersen’s Stanley Cup modifications.

Pepall does not restrict herself to Canadian artists, craftsmen, designers, architects, sculptors, and engineers. Her essays make visits to Montreal, Ottawa, Quebec City, the Arctic, Boston, New York, Haifa, Provence, Paris, Berlin, London, Venice — even outer space for an ambitious exhibition called Cosmos: From Romanticism to the Avant-garde. Without romanticizing her profession, she promotes the idea of the curator as a “treasure hunter,” modestly and sometimes literally taking a back seat as she accompanies her precious cargo to and from exhibitions. And because of that, her book is a triumphant testament to the cultural value of a true curator, minus the vanity of ego.

Keith Garebian has just published his eleventh poetry collection, Three-Way Renegade, as well as a memoir, Pieces of Myself.