In early January 2020, the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, representing that nation’s hereditary chiefs, served an eviction notice to Coastal GasLink, the subsidiary of TC Energy that is building a 670-kilometre pipeline to transport liquefied natural gas from Dawson Creek to Kitimat, British Columbia. If completed, it will cut across territory roughly the size of New Jersey that is home to over 3,000 Wet’suwet’en people in the northwestern Central Interior.

The notice came days after a second injunction was issued by a B.C. Supreme Court judge against those who had erected a camp to block the construction and assert their ancestral land rights. Although TC Energy had signed agreements with the twenty band councils along Coastal GasLink’s path — including five Wet’suwet’en bands — the authority of elected band council chiefs extends only over the parcels of reserve land created under the Indian Act, whereas the hereditary chiefs assert authority over all 22,000 square kilometres of the Yintah, or traditional territory. TC Energy failed to obtain the consent of these hereditary chiefs, including that of Knedebeas of Dark House, who helped establish the Unist’ot’en Camp a decade ago — a camp that the provincial judge also authorized the RCMP to dismantle.

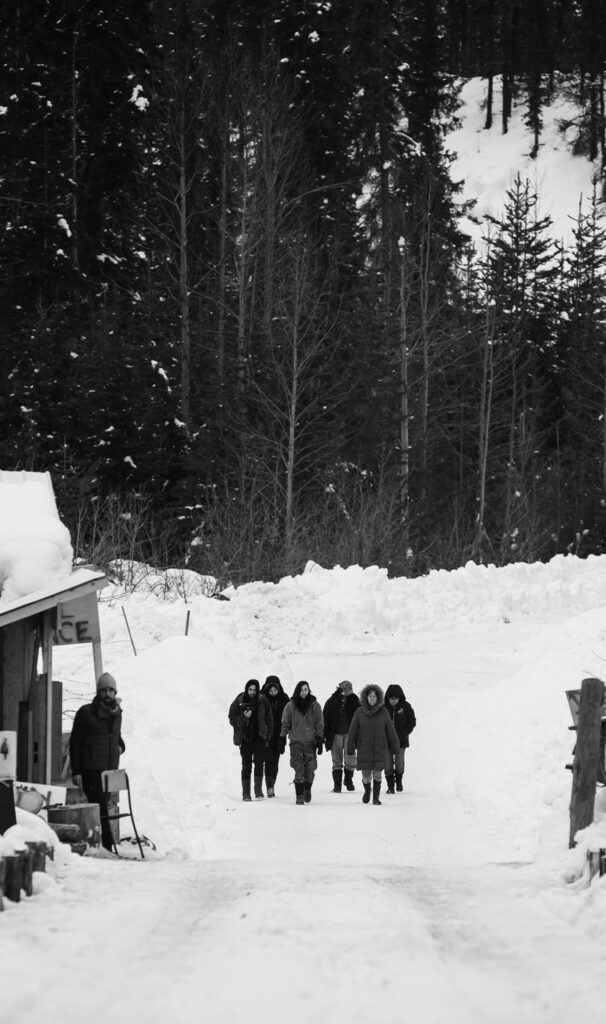

The crisis that sparked solidarity protests across the country, in the weeks before the pandemic arrived, was yet another moment that illustrates the unresolved nature of the supposed nation-to-nation relationship between the Crown and Indigenous groups — or, put another way, the chasm between the two sides’ understanding of consent.

In 2017, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously ruled that Indigenous groups do not have a veto over natural resource projects. That decision, like rulings past and since, conflates rights and interests:

A decision to authorize a project cannot be in the public interest if the Crown’s duty to consult has not been met. . . . Nevertheless, this does not mean that the interests of Indigenous groups cannot be balanced with other interests at the accommodation stage. Indeed, it is for this reason that the duty to consult does not provide Indigenous groups with a “veto” over final Crown decisions. . . . Rather, proper accommodation “stress[es] the need to balance competing societal interests with Aboriginal and treaty rights.”

When rights get conflated with interests.

The Canadian Press

But the repositioning of Indigenous rights as Indigenous interests is a category error that does not stand up to scrutiny. The Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs and other Indigenous groups strongly disagree with the court; they view their land rights as deriving from natural law — whole, primary, and intrinsic — rather than as one element in a wider constellation of Canadian societal interests. In this sense, rights that can be balanced with interests are hardly rights at all.

In very limited ways, many groups could benefit materially from natural resource projects. It’s a point the provincial judge emphasized: the “pipeline benefit agreements” had, in fact, been signed by some affected First Nations, including the elected band councils. So, arguably, by taking up opposition to natural resource projects, some Indigenous groups are acting against their own interests. Why would they do that? The answer is conveniently, if ironically, found in the same ruling:

The elected Band councils assert that the reluctance of the Office of the Wet’suwet’en to enter into project agreements, out of concern that it might negatively impact their claims to Aboriginal title, placed the responsibility on the Band councils to negotiate agreements to ensure that the Wet’suwet’en people as a whole would receive benefits from Pipeline Project and other projects in their territory.

Confronted with a Hobson’s choice of a pipeline and no benefits or a pipeline plus some benefits, the band councils resigned themselves to acting in their strictly material interests. But the Office of the Wet’suwet’en strives to achieve a more significant goal than can be captured in an assessment of interests alone: the realization of land rights.

In pipelines, we find a clash of public interests: an opportunity for questionable, short-term economic development versus pollution, climate change, and material harms to communities, Indigenous or otherwise. But the primacy of Indigenous title should make the public-interest test a secondary consideration. In a just world, it would not matter if a pipeline transported jelly beans and sunshine; the refusal of an Indigenous group would be enough to prevent its construction on its title land.

Canada has progressed toward recognizing Indigenous title in recent decades but has stubbornly rejected Indigenous sovereignty. The Supreme Court first recognized Aboriginal title when deciding Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, in 1997. Yet even in that landmark ruling , the University of Victoria legal scholar John Borrows has observed, the court’s “unreflective acceptance of Crown sovereignty places Aboriginal title in a subordinate position relative to other legal rights.”

In the view of the Canadian state, the doctrine of discovery makes Indigenous land rights secondary. While courts have set increasingly stricter standards of consultation and accommodation, Aboriginal title continues to be violated because the Crown uses a “prove it” approach that acknowledges title in theory but not in practice. As the lawyers Eugene Kung and Gavin Smith have described it, this amounts to the government saying , “Yes, Aboriginal title and governance exist, but we don’t know where exactly and it’s quite complicated, so in the meantime we’re going to continue making decisions as if it doesn’t exist anywhere.”

Consultation is not meant to sound out whether there is assent to proceed. Rather, it is meant to protect interests and reduce harms by layering on conditions, while accepting that a given project will proceed if conditions satisfying those interests and minimizing those harms are met. In a recent Federal Court of Appeal ruling , which dismissed an Indigenous challenge to Ottawa’s Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion project, the justices quoted from a previous ruling by the B.C. Court of Appeal:

Here, the appellants have not been open to any accommodation short of selecting an alternative to the project; such a position amounts to seeking a “veto.” They rightly contend that a meaningful process of consultation requires working collaboratively to find a compromise that balances conflicting interests, in a manner that minimally impairs the exercise of treaty rights. But that becomes unworkable when, as here, the only compromise acceptable to them is to abandon the entire project.

In other words, consultations are workable only when the conclusion is foregone. Indigenous groups can make efforts to minimize harms, but they have no right to say no. There is a circularity at play here: Indigenous peoples must be accommodated, accommodation requires a fair consideration of interests, and Indigenous peoples are accommodated by having their interests fairly considered. The federal ruling confirmed that, rather than their having a veto over Canada, Canada has a veto over them.

When the legal arguments are stripped away, two competing assertions of whose territorial authority should take precedence are apparent. From a statist point of view, sovereignty is a zero-sum game, and the latent self-determination of an internal group is an existential threat. So state institutions are unlikely to relent in their efforts to suppress Indigenous efforts at self-rule. That is especially true when institutional commitment to self-preservation is buttressed by an industrial policy still reliant on a resource economy, as well as by partisan and regional political motives.

Given the state’s authority and power of coercion, solutions that enable Indigenous self-determination without fundamentally threatening state sovereignty appear most realistic. One possibility is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and its principle of free, prior, and informed consent, which British Columbia recently legislated and the current federal government promises to implement. Most legal scholars agree that FPIC does not confer an absolute, arbitrary veto over natural resource projects. From there, however, two camps draw different conclusions from the same facts.

The adherents of one camp think FPIC “does not require consent for a project to proceed, but instead only requires good faith effort to obtain consent,” a matter on which “Canada already meets or exceeds UNDRIP’s requirements” (this from the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, in 2017). This camp’s primary interest is a predictable resource development process: “The critical objective must be that the adoption of FPIC does not undermine the progress achieved in recent decades to establish real partnerships with lasting economic benefits for Indigenous communities” (as another Macdonald-Laurier paper stated in 2016). If such an interpretation of FPIC prevails, it will do nothing to materially alter the landscape, and Indigenous consent will be violated again and again.

Another camp favours a stronger interpretation of free, prior, and informed consent: “Critically, where FPIC is required, consultation processes, no matter how robust, cannot be a substitute for consent” (as the Assembly of First Nations has put it). Accordingly, true consent would surpass current consultation and accommodation standards. And that would mean that some projects would not proceed where they are unwanted. Some maintain that such an interpretation would amount to granting an Indigenous veto. The Assembly of First Nations clarifies that, as others have also pointed out, the spectre of a veto is a distraction from the real issue of consent. This interpretation of FPIC is consistent with court rulings that favour dialogue and the judicial resolution of disputes, and the outlines of federalism more broadly. “No government in Canada has a ‘veto’ in relation to other governments in the valid exercise of jurisdiction,” the AFN observes. That was illustrated by the Supreme Court of Canada this year when it sided with Ottawa and said a B.C. law designed to prevent the Trans Mountain expansion amounted to a veto that contravened constitutional federal jurisdiction. But one would not describe this as Ottawa vetoing provincial legislation. Transferring defined jurisdictional authority to Indigenous peoples on title land, like decision making with respect to energy projects, can give substance to FPIC and be consistent with federalism.

Some in the pro-development camp are now less concerned with the legal interpretation of FPIC than with what its implementation might symbolize. In early March, Brian Pallister, the premier of Manitoba, worried in the Globe and Mail that UNDRIP “would enshrine in Canadian law renewed public signals that are already encouraging veto-based demands, as well as illegal blockade actions — in defiance of court orders.” Culturally speaking , the premier may not be wrong. Many Canadians are unlikely to appreciate the nuanced differences between respect for consent and the exercise of a veto. Practically speaking , if not conceptually or procedurally, the on-the-ground realities might not look any different, either: whether by withholding consent or through flat‑out refusal, the result in the end is that a project does not get built where it is unwanted.

(The implications go beyond infrastructure. One example: In June, as British Columbia moved toward stage three of reopening , many Indigenous communities wanted to keep travel restrictions in place and screen outsiders for COVID‑19. The president of the Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council, Judith Sayers, said that British Columbia’s premier, John Horgan, “cannot forget our free, prior and informed consent over our territories, and that we have not given our consent to open up the province.”)

Some advocates in the rights-first camp push the FPIC-as-veto interpretation. The Ryerson University legal scholar Pamela Palmater has written, for instance, “Indigenous peoples could exercise their legal right to refuse to approve or authorize a project. This veto right stems from various sources, but primarily our inherent rights as Indigenous governments with our own laws and rules which govern our traditional territories.” When it comes to UNDRIP, Palmater offers an uncomplicated, common sense definition:

The absence of consent means no — in other words, a veto that has real legal power and meaning. . . . Imagine if sexual consent in law meant that a man could consult with the woman on whether she wanted sexual relations, and was even willing to accommodate (“where appropriate”) her wishes about how to have sexual relations, but she had no right to say no — no veto over whether or not sexual relations occurred?

The University of British Columbia’s Jason Tockman also uses the analogy of sex, but, to illustrate why FPIC is not tantamount to a veto, he takes a slightly different tack:

Why might we think of withheld consent by Indigenous peoples for projects proposed on their territory as more of a veto than, say, a person declining a sexual advance or one person’s refusal to grant another permission to build on their private property? We would never describe those circumstances as a veto. Rather, we talk of obtaining “approval”— which conveys our perception of legitimacy — as opposed to an obstinate “veto” by which policy decisions are held hostage to an authority deemed illegitimate.

The differences between these analogies can be likened to differences between “yes means yes” and “no means no.” The latter makes one party the assertor and the other party a subject who has only the power to resist or accede, often under conditions of coercion or duress. However, the emerging “yes means yes” standard takes both parties as autonomous: that is, they proceed only if both actively agree to do so of their own volition. The party with greater power, then, recognizes its privileged status and does not use it to bully the other into agreement.

Consent discourse helps point to a way forward, because consent is tightly bound to autonomy, whether we speak of an individual’s body or a body politic. Autonomy suggests something that is less total, but in some conditions no less powerful, than sovereignty. It recognizes that parties operate in concert with one another, without one wholly ruling the other, and that their relationship will be defined and clarified by respect for each other’s basic boundaries.

Rarely have Indigenous groups called for secession, sovereignty’s logical conclusion. Their ask is considerably less than the demands of Quebec sovereigntists, who enjoyed the privilege of voting in not one but two secession referendums. Most want meaningful participation within Canada, including the freedom to practise traditional self-governance.

Quebec, of course, is territorially contiguous, and the Québécois people are, in the eyes of the typical sovereigntist, a single homogeneous category. By contrast, Indigenous peoples belong to disaggregate groups with aggregate commonalities, whose interests may overlap but also vary; only in a colonialist mindset are Indigenous peoples and interests homogenized. Within this context, autonomy expressed through consent is more workable than the sovereignty of many distinct, fragmented nations, à la Kleinstaaterei.

A Canada that is governable as a national community and that also makes Indigenous people full participants in federalism is as possible as it is desirable. Canadian sovereignty is animated by principles of federalism that govern relations between semi-autonomous, interrelated orders of government. It accounts for differences across a nation of diverse people and interests, and it enables good government by defining powers and jurisdictions and providing for methods of resolution in case of disputes. The question is how to make Indigenous people full participants in this arrangement and expand their autonomy within federalism.

Even with a weaker FPIC standard, the layering of more legislation and regulations could have the effect of “thickening” the governance space around natural resource projects and contributing to an overall dampening effect on development. But that would be a paltry half-measure compared with real structural reforms that clarify Indigenous peoples’ powers within federalism. Gordon Christie, a law professor at the University of British Columbia, points to article 27 of UNDRIP, which requires forming an “independent, impartial, open and transparent process, giving due recognition to indigenous peoples’ laws, traditions, customs and land tenure systems, to recognize and adjudicate the rights of indigenous peoples.” This would involve blending Indigenous and Canadian laws. Without that, he says, the system “protects the state.”

A federal Aboriginal Parliament Act, which the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended in 1996, could be a first step on the long road to real structural reform. The creation of a third parliamentary chamber “would give Aboriginal people a permanent voice in processes of national decision making” with “the power to initiate legislation.” Although this idea was first proposed by the Native Council of Canada (now the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples) nearly thirty years ago, during the Charlottetown Accord negotiations, it remains anathema to any province tethered to oil and gas development. Even on its own terms, such an institution might be politically ghettoizing or culturally essentializing. Nonetheless, the discussion of such ideas can help to expand the conversation on Indigenous participation in federalism.

In February, the Office of the Wet’suwet’en agreed on a memorandum of understanding with the governments of Canada and British Columbia. “Wet’suwet’en rights and title are held by Wet’suwet’en houses under their system of governance,” it reads. “Canada and B.C. recognize Wet’suwet’en Aboriginal rights and title throughout the Yintah.” The MOU also establishes a timeline for the negotiated transfer of jurisdiction on the basis of Wet’suwet’en rights and title, which will be exclusive or shared with Ottawa or the province, depending on the case. The parties expected to reach an “affirmation agreement” by mid-October.

With this document, the Crown appears to be reversing more than a century and a half of practice and planting its flag on the side of the traditional clan and house-group system — at last respecting the Delgamuukw decision. To the extent that it does, this move upends the band council system imposed by the Indian Act and legitimizes the traditional system of collective expression and leadership. And it does not mean new electoral processes can’t emerge from within the community. John Borrows, according to the Globe and Mail, thinks the dispute between chiefs “may provide a window for Wet’suwet’en people to develop governance systems that blend elements of hereditary and elected systems,” while Stewart Phillip, grand chief of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, has pitched “legitimate, legal” referendums as a way to measure consent for resource projects.

Yet consensus remains elusive. Three women belonging to the Wet’suwet’en Matrilineal Coalition who supported the pipeline say they have been wrongly stripped of their hereditary titles. They say their group, which received seed money from Coastal GasLink and a provincial ministry, was formed to consider a community benefit agreement with CGL, but that they were bullied and sidelined by the other hereditary chiefs. The Office of the Wet’suwet’en, for its part, views the coalition as an illegitimate splinter group. Each side claims a large majority of support for its position, suggesting both agree that the majority opinion matters — even as they disagree on what that opinion actually is.

Meanwhile, band chiefs have said they felt excluded from the MOU process. An August newsletter from the Office of the Wet’suwet’en acknowledges that band councils requested a stop to the negotiations and that two of them passed resolutions of non-confidence in the hereditary chiefs, who have responded with commitments to engage and listen. (Before the pandemic, local media reported the claim of a member of the Wet’suwet’en Matrilineal Coalition that the hereditary chiefs “have not held large public meetings, only smaller clan meetings of 20 or fewer people.”)

The provincial judge in the Coastal GasLink injunction case cited such internal conflicts: “The Indigenous legal perspective in this case is complex and diverse and . . . the Wet’suwet’en people are deeply divided with respect to either opposition to or support for the Pipeline Project.” She might have interpreted the absence of unanimity as the absence of clear consent to the project, but she instead found it was unclear whether the emergence of vocal subgroups represents efforts to circumvent the traditional Wet’suwet’en legal process or the continuing evolution of Wet’suwet’en governance.

The Crown has signalled it has no interest in meddling in Wet’suwet’en affairs. But while its decision to recognize and negotiate with hereditary chiefs is surely a just corrective, the irony is that even if it does not meddle directly, Ottawa invariably influences internal governance by its choice of whom and whom not to recognize and legitimize in negotiations. The band chiefs, along with the women who allege their hereditary titles were stripped away, have grievances, and some have asked the federal government to be more forceful on behalf of their interests. Of course, it was the preceding centuries of Crown rule, imposition of band councils, and disregard for the traditional clan and house-group system that helped sow the seeds for the present discord.

Perhaps there will be fewer land crises in the future, even without structural changes. There may come a day, once fossil fuels no longer drive the economy, when such conflicts are pushed below the surface for good. In the meantime, community benefits agreements may continue to pull some Indigenous groups into the pro-development camp, though recent mergers and the rise of automation in natural resource projects could lower the prospect of well-paying jobs and short-term material benefits.

Regardless of what the future holds, it’s plain that the status quo of consultation and accommodation does not satisfy legitimate claims to self-determination. It would be a shameful missed opportunity for all affected parties if they fail to imagine how to make Indigenous autonomy expressed through active consent an institutional feature of Canadian federalism.

Jonathan Yazer holds a master’s in global governance from the University of Waterloo.