Wade Davis begins his book Magdalena near the mouth of Colombia’s principal river, in Bocas de Ceniza on the northern coast, on a jetty that extends many kilometres into the Caribbean Sea. Men and women who work the surrounding waters live in shacks that precariously line the breakwater, and on their bleached walls, they’ve painted humble poetry that praises the fishing, the peace, and the sound of the waves. A narrow-gauge railway line runs between the small houses, carrying local tourists looking for the sun and perhaps a cone of shaved ice. The trains occasionally derail, and if someone has a cassette player with them, a dance might break out. But no one drinks from the toxic waterway, which is “contaminated by human and industrial waste.” Some will not even eat the fish. They remember when bodies once floated down the “graveyard of the nation.”

Many of the themes in this heartfelt and sprawling book can be glimpsed on that jetty: human violence, hubris, and the willful ignorance that so often harms the innocent and ruptures ecosystems. Yet there’s also Dionysian joy and optimism to be found in this “compendium of stories.”

In 2014, Davis, the Canadian anthropologist and honorary Colombian citizen, proposed a book, “half in jest,” about “the Mississippi of Colombia, the vital artery of commerce and culture.” He then set out to explore the Magdalena drainage basin — home to four of every five Colombians — by foot, car, and boat. With old friends, guides, and people he meets along the way, he made five extended trips in all seasons, travelling northbound the length of the country on or near the 1,500-kilometre river, from its source in the south to the sea. In describing the river — its waters, its forests, its animals and people and music and dance — Davis hopes to tell “the story of Colombia,” where he has spent time off and on since he was young. In this way, Magdalena is less of a travelogue and more the biography of a nation.

On the surface, an English-language book about the Magdalena, named after the often misunderstood Biblical figure Mary Magdalene, is not an obvious choice. Relatively few readers in North America know of the river — beyond references in Gabriel García Márquez novels, perhaps — but many know of Davis and his work. As with a good novel, we come to care deeply about the Magdalena and its characters, because our narrator himself cares about them so much.

Traditionally, the mamos — the spiritual leaders of the Arhuaco people — would periodically assess the Magdalena’s “health and well-being at every point along its flow.” For them, rivers are “a direct reflection of the spiritual state of a people, an infallible indicator of the level of consciousness a community possesses.” In other words, Davis explains early in the book, rivers are simply “the soul of any land through which they flow.” This is a truth that many of the Colombians he encounters repeat along the way.

Davis begins his journey on foot near the river’s source. At 3,400 or so metres, the mountainous Alto Magdalena region is a place of cascading water, mist, and páramos, treeless plateaus that are essential to South America’s larger hydrological cycle. Davis sets off with a botanist friend: “William led me along a dirt track that ran through a dry forest of scrub and frail acacias before turning back to the banks of the Suaza. For him, every blade of grass along the trail resonated with a story.” This motif returns again and again: the importance of grounded knowledge, whether from a traditional perspective or from a modern scientific one.

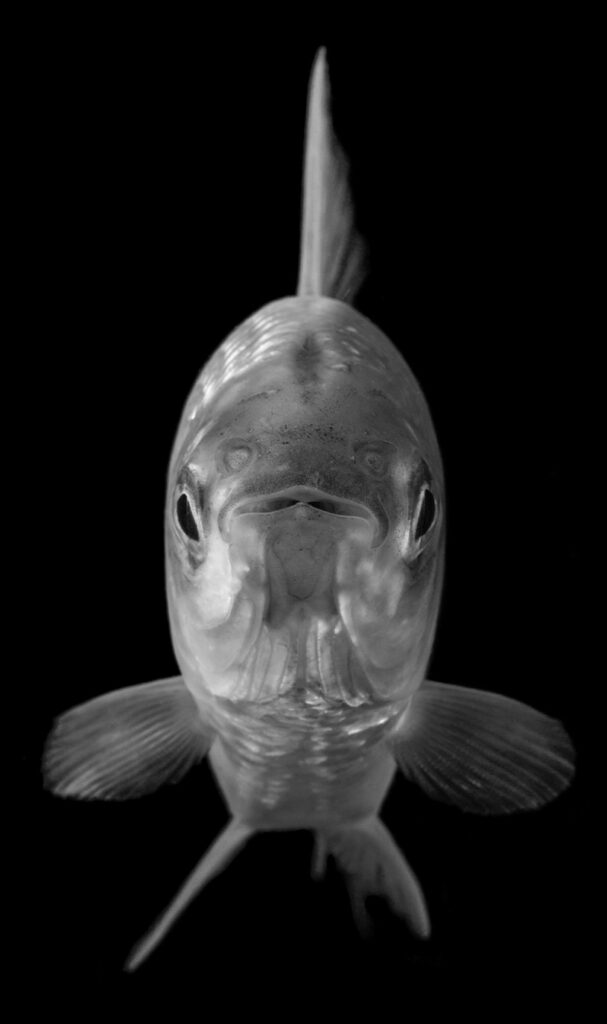

A lone face of the Magdalena.

Jorge GarcÍa, Cyphocharax magdalenae; VW Pics; Getty Images

Beauty and tragedy are tightly woven together in Colombia. Puracé National Park, for example, is home to seven snow-clad volcanoes that soar over 4,300 metres and to more than 200 species of orchids; it was also a major conflict zone during the fifty-year asymmetric war between the government, far-right paramilitary groups, and far-left guerrilla organizations, such as the FARC. The fighting ended in 2016, but not before it defined the country for many around the world. Conflict along the Magdalena is hardly a modern phenomenon, of course. The Spanish arrived in 1538, and in a clash of “Andalusian steel against weapons of wood,” the Muisca people and many others were decimated. “Within 150 years of Columbus, the original native population of 70 million in all the Americas would be reduced to 3.5 million,” Davis writes. “In the southern Andes of Bolivia, on a mountain of silver once sacred to the Inca, an average of 75 indigenous men and women were to die every day for 350 years.”

In Medio Magdalena, the river comes down from the heights, and the valley widens — thirty kilometres across in some places. It was here, in the middle, that commercialization of the river began in the nineteenth century. Steamships were a modern marvel that linked the young mountainous country in new ways, but they were also a catalyst for severe deforestation. Colombians and foreign corporations alike saw the forests as “a limitless resource that only stood in the way of development.” Felled trees powered the ships, which passengers used as “platforms for the hunting of manatees, blue turtles, ocelots, and jaguars. Men shot herons from the upper deck for sport. Children cut open the bellies of iguanas, replaced their eggs with manure, and tossed them back into the river.”

More recently, Colombia has constructed two major dams that supply nearly a quarter of the country’s energy needs: “Between La Jagua and Garzón, and for another sixty miles to Gigante and beyond, the Magdalena runs through a narrow gorge, a cleft in the landscape with the very dimensions, orientation, and geological substrata that cause dam builders to swoon.” From an engineering standpoint, these massive structures are also modern marvels. “The problem, of course, lies in the details.” Without fish ladders that would “allow migratory species to stay true to their breeding and spawning regimes,” the dams have contributed to environmental catastrophe: “Fish stocks in the Magdalena have collapsed by 50 percent in thirty years,” while the river’s drainage basin has lost nearly 80 percent of its canopy. “Erosion darkens its flow, with some 250 million tons of silt and debris each year. Few rivers in the world have been so adversely affected by sediments.” Then there are the 32 million people who flush their toilets directly into the Magdalena each day. In the management and mismanagement of the watershed, we see a country “forfeiting the future for the essential needs of today.”

The great García Márquez, who made the river “not a setting but a character in his novels,” once proclaimed his beloved Magdalena “dead.” Many others might proclaim it “ignored.” While the river is “the lifeblood of their land, the spiritual fiber of their being,” Davis describes a people who have long looked the other way. “We have always turned our backs on the Magdalena,” says one man, who has studied it for decades. “We have done so forever.” Others make the same point. “We turned our backs on the river that gave us life,” a stranger who quickly becomes a friend explains. “But to deny the Río Magdalena is to betray all that we are as Colombians.”

It’s easier to finally face the river now that the decades-long conflict has come to an end. The stories of those who suffered during the war — partially funded by cocaine, which most Colombians “have never used or seen”— are haunting. Over 200,000 innocent people died and millions more suffered. Even at the most dangerous moments, though, some stood for human dignity. One woman, in response to a dream, visited her mother’s killer in jail, listened to his apology, and forgave him. A young man — who came to be known as “the dude of the dead”— repeatedly risked his life to pick up bodies that no one would dare to touch. One town collected, buried, and left memorials to the unnamed dead, pulled from what many began to call the River of Death.

When Davis visits Medellín, he traces the career of Pablo Escobar, who once controlled drug revenues that exceeded $20 billion a year. “His net worth was $55 billion, making him the richest criminal in history. And the bloodiest.” At one point, Davis compares Escobar with Al Capone, the Chicago mobster who personally killed thirty-three. “In the decade of terror unleashed by Escobar, in Medellín alone, more than forty-six thousand would die.”

But times have changed. Escobar died in 1993, and young architects and designers have fundamentally remade the city he once terrified — focusing as much on reimagining the poor and distant barrios as on improvements to the centre — through a movement known as urbanismo social. “On a mission to save their city, they embraced and remained loyal to three articles of faith: Pessimism is an indulgence, orthodoxy the enemy of invention, despair an insult to the imagination.” As Davis shows, it’s a lesson that can also apply to the river: trees can be replanted, habitat can be rehabilitated, a new flourishing is possible — often faster and cheaper than expected. “Stories of rebirth and redemption have become commonplace as people throughout the world have embraced their rivers as symbols of patrimony and pride,” he writes. Think of the Seine, the Hudson, the Cuyahoga, the Thames.

In the Bajo Magdalena, some 240 kilometres from the Caribbean, the river actually falls below sea level and stops flowing. Mountain runoff helps push it the rest of the way: “Like the arteries and veins in the human body, a network of waterways reaches across the ancient delta to connect the snowfields of the Sierra Nevada, the most sacred destination of the pilgrims, with the river that made possible the life of the Colombian nation.”

Toward the end of Davis’s journey, an elegant retiree recounts the story of Simón Bolívar, whom the Enlightenment polymath and Magdalena explorer Alexander von Humboldt first dubbed El Libertador. “It was here that everything came together,” the retired man tells Davis. The story of a continent, of a country, of a precious ecosystem whose biodiversity is unmatched anywhere in the world — they’re all linked. “Colombia’s very freedom,” Davis writes, “won in battle two hundred years ago, grew in good measure out of Bolívar’s transcendent faith in the messages of the wild, the threads of loyalty that bind a people to their mountains, forests, rivers, and wetlands.”

In April 2018, some 4,000 kilometres northeast of where the Magdalena finally meets the Caribbean, the journalist and St. Thomas University professor Philip Lee drove from Fredericton to a village called Tide Head, four hours away, to visit with the biologist Alan Madden, “a man who knows the Restigouche as intimately as anyone on Earth.” There they first discussed what would become a worthy companion to Davis’s book, Lee’s Restigouche: The Long Run of a Wild River.

The Restigouche, though diminished from its former glory when the salmon runs were “prodigious,” remains a great salmon-fishing river. And Lee knows it well. He’s camped beside it, canoed upon it, and fished it since he was a child. He has also witnessed the quickening pace of ecological damage:

In each new season I watched assaults on natural systems spread through the valley. Some I have seen with my own eyes: the logging trucks rumbling down from the hills twenty-four hours a day; the cuts growing larger and creeping ever closer to the river; feeder brooks that once flowed through the summer now dry and choked with sediment washed down from nearby logging and more distant industrial enterprises. The hills have been sprayed from the air with pesticides and herbicides, and the old mixed forests transformed into new monoculture tree plantations.

Even as he has watched the degradation in real time, he has wondered, How did this happen?

Over the years, study after study has predicted “the numbers of direct and indirect jobs that will be created and tax revenues that may be collected” through resource extraction in New Brunswick, but Lee has rarely seen the living place he knows reflected in the technical reports about the Restigouche. So he asked himself a question not unlike the one Davis asked over and over in Colombia: “Could a truer measure of what’s worth saving be found in the story of the life of one wild river?”

As it flows for 200 kilometres, northeast from the Appalachian Mountains to Chaleur Bay, on the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, the Restigouche marks the border between Quebec and New Brunswick. Lee organizes the river’s story around three extended canoe trips, where he was joined by family members and friends who know the waterway intimately. These trips were joyous, meditative, and occasionally rain soaked. “The inevitable difficulties and hardships we encounter on trips such as these,” he writes, “and in the passages of our lives, are necessary obstacles to overcome. Sometimes we have no choice but to pull our canoe over a shallow gravel bar or shoulder it across a portage. In my life, I’ve done my share of both.”

Lee offers plain, concrete descriptions of the life that flows around him, which he complements with engaging chapters on the complex, multi-layered history of the region, using excerpts from original documents wherever possible. Of course, human violence, hubris, and willful ignorance have played out in New Brunswick too. So as we learn of great fishing pools and iconoclastic river guides, we also learn of a billionaire family that controls an “industrial forest” that covers 200,000 hectares and of a mid-century hydroelectric scheme billed as the “economic salvation of our province.” Constructed in the 1960s, the Mactaquac dam, upstream from Fredericton and capable of generating 20 percent of the province’s power, was “designed to transform this great river into an asset.” But it has ravaged salmon stocks on its way to becoming “a liability for an already highly leveraged power utility.”

Lee also integrates the long-ignored history and deep culture of the Mi’gmaq, who have lived intimately with the river for generations. Signed in the mid-eighteenth century, the Peace and Friendship Treaties “confirmed their right to fish and hunt in their traditional territory,” but the British did not honour those guarantees on the Restigouche, where colonial officials introduced “the common law tradition of private fishing rights and a history of regulation that gave priority to angling over harvesting for food with nets or spears.” Angling was a “refinement of a civilized people,” and eventually New Brunswick began leasing exclusive fishing rights along the river to those who were, purportedly, the most refined. In June 1880, Chester Arthur (soon to become the twenty-first U.S. president), Charles Lewis Tiffany (the jeweller), William Kissam Vanderbilt (the railroad tycoon), and others of New York’s super elite bought roughly 650 hectares and formed the Restigouche Salmon Club. That was just the beginning.

Soon it wasn’t only the Mi’gmaq who could no longer fish their river; most citizens of New Brunswick were kept away by leases that were sold to the highest bidder. A century after the Restigouche Salmon Club was founded, in what came to be known as the Battle of Larry’s Gulch, local residents protested the lack of public fishing access before being dispersed by the RCMP. From fishing rights to the management of Crown forests, Lee describes how rich families and corporations have long wielded too much influence over the Restigouche. “It’s a situation in which there really is a deficit in terms of democratic decision-making about our natural resources,” he quotes the historian Bill Parenteau as saying.

Corporate influence has even affected conceptions of time in the region. In 1876, the Scottish-born Canadian engineer Sandford Fleming “opened the river valley to the world” with a railway bridge downriver from Matapédia. With the rail lines came economic development and an imposed temporal standardization: “We all now live according to the practical and predictable rhythms of the same clock that is regulated by the artificial lines we have drawn across our maps,” Lee writes. “But the river still keeps its own time.” To acknowledge this, Lee maintains, is to acknowledge the flux of creation, a Mi’gmaq concept and way of being based on an understanding that people “are all part of a divine process in an ever-changing world.” With more river leases coming up for auction in 2023, he sees that understanding as key to the wise stewardship of the Restigouche going forward. Lee knows the value of science, but he suggests that we can mistake abstraction for life and often forget that we too are part of nature.

One day, while watching an eagle ride the updrafts, Lee thought of the writer and senator David Adams Richards, who has spoken of the “spiritual readjustment” one can draw from a river. “We have too much, we fret too much, we hoard away too much for ourselves,” Richards has written. Spending time on the water, however, can remind us that “human kindness matters, and companionship, and our love of and protection for those who are far away from us at that moment, but not much else.”

A newspaper editor once told Lee more or less the same thing: “A true story well told becomes a parable.” Indeed, the well-told story of the Restigouche, like the well-told story of the Magdalena, has much to teach us. Though degraded and though different in many ways, both rivers are what Davis describes as open books —“with countless pages and chapters yet to be written.”

Robert Girvan is a former Crown prosecutor and the author of Who Speaks for the River?

Related Letters and Responses

Marc Allain Chelsea, Quebec

Philip Lee via Facebook