Aren’t all the best myths really about the price of information? We have Adam and Eve ousted from Eden for wanting “the eyes of them both [to be] opened.” There’s poor Prometheus, who gets his liver pecked in perpetuity for disclosing the secret of fire and “all manner of arts” to humans. And there’s Odysseus, beckoned by the Sirens’ perilous revelation of “everything that happens on the fruitful earth.” In each case, the moral of the story is the same: you don’t want to know.

It has not stopped us from trying. In the post-Enlightenment era, the continuous acquisition of knowledge has become our prerogative. It’s telling that the different versions of the Faustian myth — one more story about the price of information — fundamentally recast its hero following the Enlightenment. The sixteenth-century playwright Christopher Marlowe, for example, condemns Faust’s hubris and rewards his megalomania with eternal damnation. By Goethe’s time, in the early nineteenth century, Faust is redeemed. His defiant striving toward godlike knowledge is now bold rather than foolish. He is the original infovore, forever scrolling down and forever demanding, “More, please.”

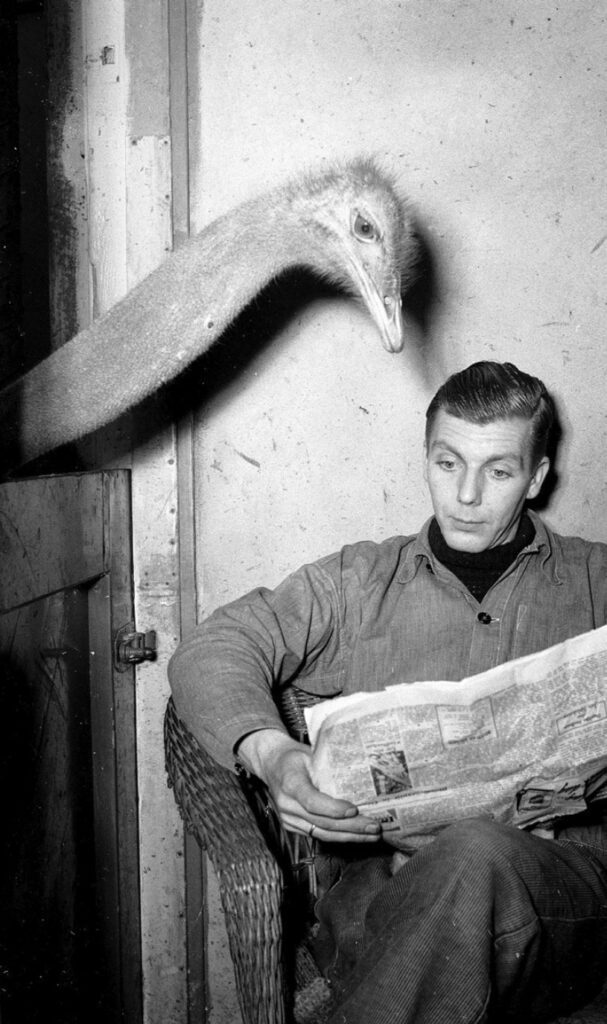

We accept the premise that rational decisions ought to be made on the basis of all available information, and that more of it is therefore better. People of reason prefer to know. They look reality in the eye. They read the full contract before signing it. If their spouse has been unfaithful, they’d like to be told, so that they can calmly choose the best course of action. If they have a predisposition to a degenerative illness, they want to find out, even if no treatment is available. They stay on top of the news, even when it’s bad. In fact, isn’t there something morally dubious about preferring not to know? We rarely sing the praises of the ostrich with its head in the sand.

Yet our high-minded celebration of maximal information often proves self-deluded. Despite our assurances that we can handle the truth, many of our actions suggest that we prefer not to. We constantly ignore information or attend to it selectively. People check their investment portfolios more often when the stock market is up than when it is down. They conveniently overlook the calorie counts on restaurant menus, especially if they are prone to indulging. Those who tend to overspend blind themselves to prices: they actually manage to not absorb the information, though on a subliminal level their minds know it’s there.

Whose head is in the sand now?

Anefo/J. D. Noske, 1951; Nationaal Archief, The Hague

In many cases, such a preference for not knowing is actually rational: it is the correct choice given the effect that learning something would have on us. The process of gathering information, for starters, can be long, costly, and tedious. A few years ago, researchers calculated that it would take us seventy-six days to read the privacy policies we agree to every year. Exposing ourselves to some truths can also make us sad or upset. Or it may worsen our behaviour. On further reflection, we may prefer not to know what our spouse is up to when we’re away, lest we react less rationally than we’d hope. Knowing how the evening news makes us anxious and distressed, we might opt not to watch it. As I recently learned, parents-to-be must repeatedly choose how much they want to know — and when. There’s the boy/girl question but also weightier ones, like deciding whether to test for Down’s syndrome and a long list of other low-probability conditions, from sickle-cell anemia to Tay-Sachs disease. For weeks, I felt the full burden of the Enlightenment weighing on me. Reason can get us only so far in such cases, which is why the choices of reasonable people about which information to seek vary.

As it has become easier to know — through the advent of Wikipedia and at‑home DNA testing along with nutritional content listings, warning labels, and those forty-page disclaimers — it has also become easier to grasp that we may, in fact, prefer not to know.

This leaves governments — often the ones deciding whether we ought to be told something — in an unenviably tricky position. For the most part, the design of our political institutions has assumed an Enlightenment model of the citizen. They cater to our most rational selves, even when we happen to fall short of that standard. People claim they have “a right to know”; according to this mantra, they ought to be given all the information so they can decide for themselves.

The result has been a steady march among democracies toward ever greater disclosure. In 2005, Canada became the first country to make the labelling of all trans fats on prepackaged foods mandatory, to help consumers make better dietary choices. Two years later, Ottawa mandated that all prepackaged foods list their full nutritional content. Drug companies, insurance firms, car manufacturers, mortgage lenders, real estate agents — all are required to provide us with information that’s meant to help us make better decisions.

There are even government-mandated disclosures about disclosures: online companies must now tell us what they will do with what we tell them about ourselves. Fewer than 3 percent of us bother to read those privacy policies, however. As a result, most of us draw the wrong inference from their existence: 75 percent of people think a privacy policy provides additional protection for their information, whereas it usually represents a relinquishing of it. Similarly, those who would gain most from reducing caloric intake are least likely to read nutritional tables. Given our false inferences and selective attention, are governments right in requiring firms to provide us with all this information?

The answer is all the more unclear given that it can be upsetting to know. When fast-food customers are told the amount of saturated fat in a meal they nonetheless want to order, they may feel they have been robbed of a pleasure. Smokers who are reminded of the health impact of a habit that they refuse to give up are likely to be aggrieved by the reminder. Should such emotive effects count when deciding what information to provide? Should governments care not only about how a disclosure makes us behave but also about how it makes us feel? Should they honour our whims, our biases, our foibles? Should they correct for these, like a concerned parent? Or instead accommodate them, like an understanding friend?

These are the questions at the core of Too Much Information: Understanding What You Don’t Want to Know, by the Harvard legal scholar Cass R. Sunstein. According to its main claim, governments should respect our quirky and distorted selves, those revealed through our sometimes incongruous behaviours, rather than the Enlightenment ideal of a rational citizen, which we rarely live up to. And, as the book’s title suggests, that often means providing people with less, rather than more, information.

Sunstein may be as well placed as anyone to address the tangle of issues surrounding the question of which information to provide. He is the co-author of Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wellness, and Happiness, from 2008, which was an attempt to apply lessons from behavioural science to government policy. That book was co-authored with Richard Thaler, a University of Chicago economist who was awarded the Nobel Prize, in 2017, for his research in behavioural economics.

The central idea of Nudge is that governments can guide people to better outcomes by redesigning how choices are presented while preserving the freedom to choose. Lives can be saved by changing the default option on organ donor forms, for example, since most people never deviate from the default. Children can be encouraged to eat healthier food if the vegetables are served at the beginning of the lunch counter rather than at the end. In the world of Nudge, small, harmless-sounding interventions can lead to better outcomes.

In 2009, Barack Obama named Sunstein his “regulation czar,” which allowed him to test out some of his ideas in the real world. That appointment was seen in some quarters of the United States as a sinister takeover of government by paternalistic regulators who would rob Americans of their freedoms. Sunstein might have picked the wrong country to pitch his ideas in. Tellingly, behavioural insights have found a more welcome reception in policy communities outside the United States. The United Kingdom and Canada, in particular, have been leading the charge. Both the government of Ontario and the Canadian federal government have created “impact and innovation units” that prioritize behavioural insights of the kind that Sunstein has championed.

That stint in the policy world led Sunstein to revise some of his own beliefs about the right to know and the obligation to inform. One episode, in particular, seems to have precipitated a change of heart. In Washington, Sunstein successfully pushed for regulation mandating that all restaurants and movie theatres disclose the calorie content of all the food they serve. Learning this, a friend of Sunstein’s sent him a three-word email: “Cass ruined popcorn.” Standing accused of ruining a beloved puffed snack has caused Sunstein much grief, and it has provided the motivation for this latest book.

Sunstein proposes that information should be provided according to a simple rule — namely, whether it “would significantly improve people’s lives.” To his credit, he offers a disclosure of his own, admitting how that simple-sounding rule is “perhaps deceptively so.” Indeed, what Sunstein proposes turns out to be a tall order: he suggests that regulators should fully take into account the behavioural and emotive effects of potential disclosures in deciding whether they would make people better off.

Assessing what “better off” means is the nub of the issue. One way of going about it is to simply ask people what they want to know. But here, too, people’s quirks make this difficult. It turns out, for instance, that most people say they don’t want to see calorie labels in restaurants, presumably because they want to enjoy their poutine without being reminded of its effects on their hearts. As consumers of cheese curds and fries well know, “he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow” (Ecclesiastes 1:18). Yet the same individuals overwhelmingly favour regulation to force restaurants to disclose the calorie content of the food they serve. Sunstein calls this an “evident paradox,” and he generally wants to place more weight than we currently do on how information makes people feel — rather than merely how it makes them behave. In other words, he regrets ruining popcorn.

In cases like these, Sunstein’s attention to people’s many irrationalities may lead him to underestimate the depth of their reason. If we want firms to list all their ingredients and their terms and conditions despite not wanting to read any of the details, that might be because we believe that if they were hiding something untoward, someone would alert us to it. This may reflect a faith in markets, another characteristic belief of the Enlightenment: we trust in the market’s singular information-crunching powers, and we similarly trust that someone somewhere has a market incentive to flag harmful actions by firms.

Or else we may sense that we do not need to pay attention to the information ourselves, because the main effect of the disclosure is on the companies doing the disclosing. That effect is, in fact, supported by evidence: a survey of menus following a mandate to disclose calorie contents showed that restaurants shifted their offerings toward healthier options. This too, incidentally, is a product of Enlightenment ideas. Jeremy Bentham, the father of utilitarianism, dreamed of a model prison, which he called the panopticon: a design where a single guard could watch all inmates without their knowledge. The idea was that the mere possibility that they were being observed would improve their behaviour. Bentham’s little design has gone down in history as an example of how technocrats’ dreams can turn into nightmares. We may nonetheless have internalized its insight. We don’t need to read the caloric warnings, as long as restaurants know that we could.

When spendthrifts ignore prices or gluttons ignore calorie counts, it’s easy to take the high-minded Enlightenment position: responsible people ought to know, so let’s make sure that they do. But what about cases where self-deception might prove useful?

I face this dilemma myself whenever one of my students considers pursuing a PhD. A warning label might read: “About half of graduate students never obtain their doctorate, and only 10 to 25 percent of those who do end up with tenure-track jobs.” How much should I insist on such a disclaimer?

What complicates matters is that while I believe in my duty to inform students of their chances, I also think that they might be better off ignoring me. Those who end up succeeding on the academic market often get there by paying no heed to the odds. This approach might actually prove strategic. We know from experiments in social psychology that self-deception of this sort can lead to greater persistence at difficult tasks and higher odds of success. For that matter, people more prone to self-deception appear happier in the present, and they have more positive expectations of their future. How much should governments be guided by such findings? Ultimately, I agree that self-deception can be useful; but I might prefer that it be up to individuals to deploy it. Which is why for calorie counts, as for the academic job market, I ultimately come down on the side of providing more, rather than less, information.

But things get trickier still. We know the precise cardiovascular implications of poutine and the odds of the academic market. But what if the costs and benefits of a disclosure are unclear? Since 2012, the United States has required that all publicly traded companies list any use of “conflict minerals” in their products. These include tin, tungsten, and tantalum — all found in a range of tech gadgets, from phones to laptops. These minerals often come from conflict zones, especially around the Great Lakes region of Africa, and the concern is that their mining may help fund violent rebel groups, increasing conflict and suffering. Canadian firms listed on American stock exchanges must follow the disclosure rule, but Canada has yet to adopt similar legislation, despite repeated attempts by some members of Parliament.

When the U.S. agency tasked with implementing the law tried to estimate its impact on conflict, it found it couldn’t: the causal chain was simply too long. From a consumer’s decision not to buy a product based on its sourcing, to a company’s decision to change suppliers, to the impact that such a change in demand has on conflict on the ground — it became impossible to calculate what the final effect might be. In fact, it was suggested that the regulation might harm the very people it is aimed at protecting by depriving them of a livelihood. Such unintended consequences are what government regulators lose sleep over at night. But regulators are also in a better position than consumers to work through adverse effects. So should the information disclosure be required at all?

In this case, Sunstein does not come down clearly on one side or the other. Sticking with the idea that we should honour how information affects people’s feelings, he suggests that the “warm glow” that some consumers get from choices based on moral convictions — such as not buying a product that contains conflict minerals —“should be counted” when making policy choices. But then he immediately adds that “agencies should do the best they can to determine whether disclosure will, in fact, counteract a moral wrong.” He goes on, “There is a risk that morally motivated disclosure requirements will be merely expressive, producing a sense that something has been accomplished without actually helping anyone.” This strikes me as trying to have it both ways: governments should at once take into account the moral vindication that people get from seeing their beliefs validated by policy and stick to a policy’s objective effects. Each sounds desirable, but they will often be incompatible. Either we value people’s feelings and their moral beliefs, or we recognize that those feelings and beliefs are sometimes misguided and that it is the duty of government to parse the evidence with greater care.

The broader point is that information is not neutral if it is mandated. Citizens draw inferences from seeing their government require firms to disclose their use of conflict minerals. They reasonably conclude that consumption of such products must aggravate a moral wrong. The warm glow of moral vindication, in other words, is itself premised on governments doing their due diligence — rather than being guided by said glow. In cases like these, this deference to authority may be the best indication that people expect their public institutions to disregard the way information makes them feel, in favour of an objective assessment of the facts. Consumers can be led by whims, but governments probably shouldn’t be — even when the whims in question are those of their citizens.

It is this issue of trust that is the biggest omission in Too Much Information. I don’t know whether “ignorance is bliss,” as Sunstein maintains is often the case, but it surely is a luxury. That’s because one needs to know a great deal to know that one doesn’t want to know. To choose whether to be told the calorie content of a cheeseburger, we effectively need to know the calorie content of a cheeseburger. In deciding whether to be informed of the genetically modified content of a tomato, it helps to have formed an opinion about the health consequences of GMOs. For this reason, choosing not to know often assumes that someone else does. It also assumes that this someone else can be trusted to know that we need not be told — either because it would be ineffective or because it would make us sad or upset.

As a result, it strikes me that Sunstein’s change of heart about information disclosures represents a greater delegation of power to governments than his prior work on nudges. Indeed, the fundamental premise of Nudge is that the proposed policies preserve choice: I can still choose whether to be an organ donor; it’s only the default that has changed. In this sense, it’s the disclosures that are themselves a kind of nudge: I can attend to or ignore the information, but it is the government’s way of nudging me away from a tech product that contains conflict minerals. It follows that refraining from that informational nudge may not, in fact, preserve choice. If I am not told which products are made using conflict minerals, or whether a tomato contains GMOs, then I cannot choose to be told in order to make an informed decision.

Another reason that less information may end up limiting choice is that information disclosures are often substitutes for hard rules. Rather than legislating, say, a total ban on trans fats (as several countries are contemplating), regulators can require that consumers be informed and leave it up to them to make up their minds. A preference for not inundating consumers thus makes it more likely that tougher policies like outright bans, which are explicitly designed to limit choice, will be put in place.

Of course, there is nothing intrinsically wrong in limiting people’s choice. Forsaking choice is largely the point of advanced democratic societies. We let health authorities worry about tap-water quality so that we don’t have to monitor it ourselves and decide whether to boil it every morning. If we had to be fully advised of all the safety features on an airplane before making an informed decision to take off, we would never end up boarding. We are constantly choosing not to choose, knowing that we do not know, and trusting that others do. Advanced market societies are based on such delegation of power, which does not take away from the fact that every time we consent to ignorance, we place a little bit more trust in policy makers’ benevolence, as well as in their competence. To opt not to know, then, can be thought of as the privilege of those lucky citizens who believe policy makers’ incentives are highly aligned with their own.

Yet the fact is that governments face conflicting pressures on information disclosure, something that Sunstein also leaves unaddressed. These pressures arise, first, because disclosures are expensive: meeting the American requirement on conflict minerals was estimated to cost companies $4 billion (U.S.) in the first year alone. As a result, industries often lobby against information disclosures. At least part of the reason Ottawa has not followed Washington’s example on conflict minerals is the pressure by the Canadian mining sector, which regularly ranks among the most active special interest groups on Parliament Hill.

More deviously, some corporations actually love information disclosures, precisely because of the high costs entailed. The biggest food manufacturers have thus been oddly favourable to rules mandating ever more detailed nutritional label requirements. That’s because it plays to their competitive advantage: they can absorb the costs of analysis and relabelling, while small firms often cannot. Similarly, the largest firms can put out a new product overnight that is free of trans fats, MSG, or gluten, while mom-and-pop shops struggle.

Neutral-sounding disclosures are not neutral if they benefit large firms at the expense of smaller ones. Such competitive effects explain why governments are sometimes so keen not only to mandate those disclosures but also to impose them on their trading partners. In an era of low trade barriers, labelling requirements can be deployed as a substitute: it’s often easier for a country’s own producers to meet complex national requirements than it is for foreign producers.

In a landmark international dispute that concluded in 2015, Canada challenged a law that required that beef sold in the United States bear a label informing consumers exactly where the cattle were born, raised, and slaughtered. Canada claimed that the measure was disguised American protectionism and more trade restrictive than necessary. The World Trade Organization ruled in Canada’s favour. The legal concept at issue is “country of origin labelling,” which trade lawyers refer to by its acronym, COOL (though it is anything but). Think of it as the weaponization of paperwork. When domestic producers have an easier time clearing regulatory hurdles, they often insist that those hurdles be made into a requirement for others. The result is excessive paperwork and red tape — something that the economist Richard Thaler, Sunstein’s Nudge co-author, calls “sludge.” And while sludge is often portrayed as the result of bureaucratic overzealousness, it is just as often the result of clever corporate manoeuvring.

When people delegate power over information to governments, they do so trusting that policy makers will steer through these competing pressures and appropriately balance people’s well-being with corporate interests. This belief places tremendous weight on one’s faith in government, which may explain why countries other than the United States have shown the most interest in Sunstein’s ideas. International surveys suggest that places like South Korea, which enjoys very high levels of trust in government, are most open to the idea. Countries like Hungary, where citizens have greater mistrust toward the government, are most strongly opposed.

In the past year, the connection between information and trust has gone from an academic question to an item of dinnertime conversation. The management of COVID‑19 has turned in large measure on what information — and how much of it — to broadcast in the face of rising death tolls, scientific uncertainty, and varying levels of popular denial and complacency. Early on in the pandemic, some governments suppressed information to limit public panic. In some cases, data on questions like the effectiveness of masks appears to have been misrepresented to stave off hoarding, in an effort to retain enough personal protective equipment for front-line workers. As a result, the credibility of government-provided information has been a key concern. Not coincidentally, those same countries that feature high levels of confidence in government have also proven best at tackling the virus. The pattern seems to hold even within countries, as the case of Canada suggests. Quebec and Alberta feature this country’s lowest levels of trust in government; they have often seen the worst per capita numbers in the most recent wave of the virus.

Policy makers have been drawing on behavioural insights at every stage of the pandemic response. Survey experiments have been used to design public signs about handwashing that yield the optimal behavioural outcome, for example. In support of Sunstein’s contention of “too much information,” it seems that if these signs include too many steps, people retain less rather than more of their content. Nudge principles have been used to recruit volunteers for vaccine trials. And behavioural science may have the most to offer in getting those parts of the population that remain skeptical of vaccines to nonetheless get inoculated, and to return for that second jab.

The global vaccine rollout began, of course, just as many countries were seeing record-high rates of infection. In response, some health experts called for governments to disseminate even more information, with the explicit intent of scaring people, along the lines of public service ads against smoking. This tactic too draws on a well-established behavioural finding: namely, that people are more swayed by personal stories than by abstract numbers. The ubiquitous exponential curve on the front page of newspapers is one thing; graphic images of patients on ICU ventilators are another. The point of using fear would be to upset people for their own good.

In arguing the merits of information disclosures, Sunstein draws on the most recent findings in behavioural science research. Yet the irony is that, cutting-edge though it may be, behavioural science often finds itself playing catch‑up with the market. Advertising departments have long been acting on the very insights that social psychologists and economists are busy demonstrating through fancy lab experiments.

By pushing governments to take into account how information makes people feel, Sunstein thus finds himself arguing that policy makers ought to think more like marketers. Their objectives may differ, but the approach would be the same: to anticipate people’s irrationality, their biased self-image, and their weaknesses, and to exploit them — either to move product or “to improve people’s lives.” In fact, Sunstein assesses whether people actually want to be informed of something based on their willingness to pay for it (a criterion that he also duly criticizes, but without providing a better alternative). It thus turns out that people would pay an average of $154 to know the year of their death (while others would pay not to know it) and $109 to know whether tech products contain conflict minerals. Of course, this willingness to pay is the very criterion that drives marketers. If people want to know, it means someone in the market has an incentive to tell them.

Seeing what such incentives have wrought in the market, however, underscores the limits of Sunstein’s simple-sounding rule. In their never-ending bid to please consumers, markets are constantly creating novel grounds on which to do so: they invent desires so that these might be satiated; they come up with fears so that these might be dispelled. I still don’t exactly know what bisphenol A is, but, seeing the proliferation of “BPA-free plastic” labels, I know I’d rather not have any of it in my newborn daughter’s toys. Similarly, the preponderance of scientific evidence indicates that genetically modified foods have no adverse effect on human health, which is why the Canadian government requires no disclosure of GMO content. Yet this does not stop advertisers from eagerly promoting their foods as GMO-free. It is one more way for brands to differentiate themselves. That then shapes people’s perception of what’s safe and what’s not, which in turn increases the perceived value of those labels. Marketing executives everywhere rejoice.

The conclusion the market has drawn is that affluent consumers want ever more information, and they are willing to pay dearly for it. And the market has delivered. The result is that our desire to be informed is starting to get in the way of our knowing. An average can of tuna, for example, is now adorned with a tapestry of labels and logos, each assuring consumers of the utmost virtue of its contents: its performance on matters of ethics, environmental protection, sustainability, carbon neutrality, organic standards. In Canada, there are over thirty officially recognized eco-labels for canned tuna alone. There’s a case to be made that as a result, we are now less able to make educated decisions than we were when we had less information in the supermarket aisle. In fact, in ways that I suspect Sunstein would be sympathetic to, here is a natural role for regulators to play. When the deluge of information gets in the way of people making better decisions, regulators may want to start imposing limits on how much information consumers face when choosing which can of fish to purchase.

Consumers have not sat idly by, mind you. By now, we have exquisitely honed defence mechanisms against the market’s exploitation of our weaknesses. We are terribly savvy consumers: we know better than to take those labels at face value. We instantly picture the focus groups over at Seafood, Inc. being used to measure our willingness to pay premium for tuna-can virtue. And we adjust our behaviour accordingly.

One risk of prodding governments to think like marketers — to encourage them to push our buttons “to significantly improve our lives”— is that we may develop analogous defence mechanisms against mandated information, even when it’s information we truly need.

In the Soviet-era Poland where my parents grew up, a common joke was that whenever the weather forecast called for sunshine, it was best to pack an umbrella. Announcements of record economic output left people worrying about what bad thing the regime might be trying to conceal. The one human bias that Sunstein leaves out of his probing discussion is a universal and deeply ingrained distaste for being manipulated — even when it is for our own good. The use of behavioural insights by policy makers relies on considerable trust, but it also risks eroding that trust if it is deployed too eagerly.

I remain highly sympathetic to the use of behavioural insights in policy making — which Sunstein’s work has contributed to — and especially the evidence-based methods it relies on, like randomized control trials. Then again, I’m rather biased. These are the methods I use in my own research, now suddenly being adopted by policy makers. And everyone likes to see their work finally get some recognition, don’t they?

Still, I remain uneasy about Sunstein’s claim in Too Much Information that regulators should take into account how information makes people feel in deciding whether to provide it. The simple-sounding rule that people ought to be informed only if it makes their lives significantly better implies a degree of omniscience that may be beyond anyone’s powers. And it leaves out how people’s behaviour may adapt in turn. It seems to me safer to lean toward the Enlightenment model of the citizen — faulty though it may be — and disregard our feelings altogether. People are indeed prone to quirks, biases, and self-deception. But perhaps individuals ought to be the ones wrestling with these as best they can, rather than being protected from them by benevolent regulators.

Information does come at a price. And its disclosure is rarely neutral, especially when governments are the ones mandating it. Ultimately, popcorn may best be ruined.

Krzysztof Pelc is a professor of political science and international relations at McGill University.