As kids, my brother and I shared a room on the third floor of our house, directly across the street from a modernist grade school, its mostly windowless facade a slab of concrete four storeys high. From the vantage point of my bed, all I could see was an expressionless grey presence, brought to life only by the buzz of a giant ventilation system. And though I looked at it every day for years, I never gave the monolithic expanse much thought.

Whether we realize it or not, the beauty and the menace of concrete stare us in the face throughout our lives, so much so that we’re more or less desensitized to its omnipresence. That solidified mixture of gravel, sand, and cement covers the ground we travel. It undergirds our skylines and waterfronts. It defines how we live. Long ago, our forebears celebrated concrete as a symbol of technological progress; now its pervasiveness means we largely ignore it.

For many, an interest in playing with the earth starts and ends in the sandbox, but for others — like the 58,000 who typically attend the World of Concrete convention in Las Vegas each year —“dirt work” becomes a lifetime obsession, an obsession to mould the earth. For the ancient Romans, this impulse fuelled a quest for beauty — so that citizens could commune with the gods. And where better to do just that than the Temple of All the Gods? Two thousand years later, tourists and engineers alike still marvel at the Pantheon’s soaring rotunda, topped by the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.

In modern times, secular practicality tends to win the day. Concrete helps on that front too. It’s strong, durable, and cheap. It can be formed into almost any imaginable shape. It lets builders get the job done quickly and with relatively little skill (pouring liquid concrete from a mixer or assembling structures with Lego-like concrete blocks is hardly the stonemasonry of the past). Best of all, its raw materials — limestone and aggregate — can be found almost anywhere on the earth. Along with water (also a key ingredient), concrete is now among the most abundant substances in the world, certainly the most widely used building material in history.

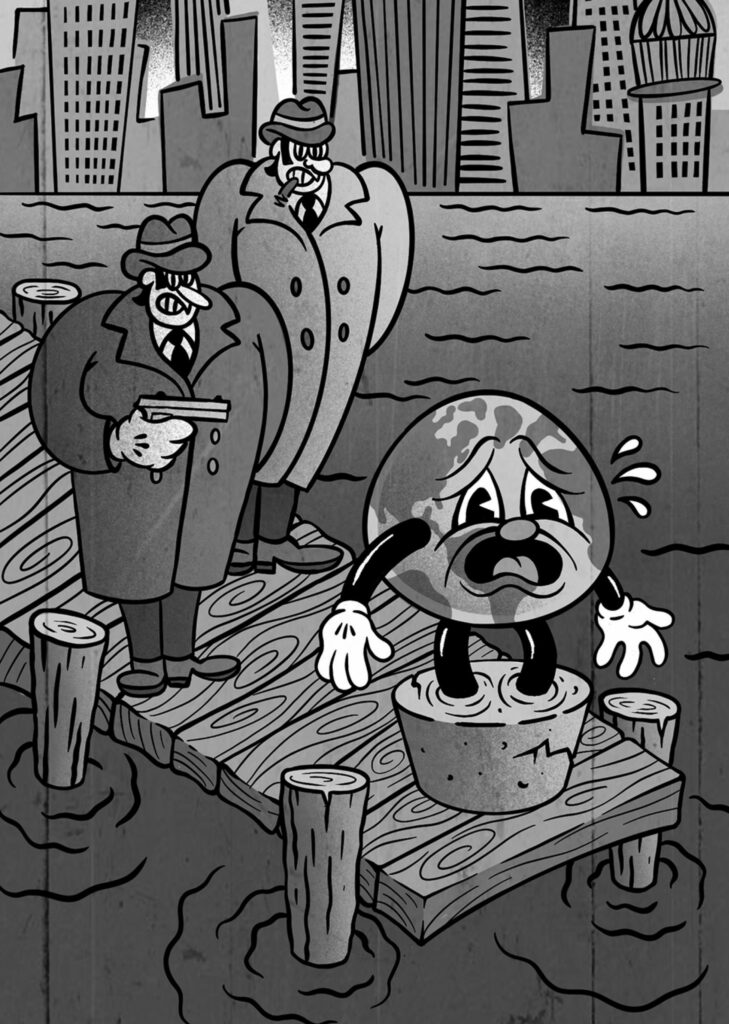

Built upon and threatened by concrete.

Alex MacAskill

That’s a staggering fact but maybe not a surprising one. “Concrete” literally means “grown together,” and that’s what it has allowed us to become. The skyscraper was born in Chicago just 136 years ago. Now 4 million high-rise buildings dot the planet, with another 3.5 million in the works. Concrete makes most of those possible. It also makes possible the massive pipes and aqueducts that deliver water to our taps. We owe our diet, in large part, to extensive concrete irrigation systems that keep farmers producing year-round. If not for hydroelectric dams built of concrete, millions would be without power.

When it comes to “providing security, protecting populations, establishing stability and eliminating terrorist threats,” John Spencer of the United States Military Academy has argued, nothing has more going for it than concrete. The atomic bomb would not have been possible without the concrete barriers used to protect scientists from their atom-splitting experiments. Similar structures now keep radioactivity contained in nuclear power plants. Chemotherapy and X‑ray technologies also owe their existence to the resiliency of concrete, which is leveraged to keep practitioners and patients safe.

The United States, a superstar of twentieth-century development, was by far the largest consumer of concrete between 1901 and 1999. It built thousands of towers and iconic dams expected to last eons, not to mention the longest and most sophisticated highway system in the world, resting upon a concrete bed. But America’s consumption of yesterday is a drop in the bucket compared with what’s happening in Asia today. China, which now pours 60 percent of the world’s concrete, went through more of the stuff in just three recent years than the U.S. did over a full century. With unprecedented population growth and dozens of countries developing at previously unimaginable paces, have we simply fitted the planet with concrete shoes?

In Concrete, Mary Soderstrom aims to deepen our awareness of a substance that shapes and, increasingly, threatens our lives. While she acknowledges its many undeniable benefits, she focuses on the very real effects of its continued use in an era of climate crisis. This is the tragic tale of ubiquitous invisibility.

Consider the production of cement — the glue that keeps concrete’s ingredients together:

Two elements of the process of making cement produce CO² directly. First, the temperatures needed to reduce limestone or other similar rock to its basic components are extremely high, requiring burning great quantities of fuel. Second, the chemical process itself liberates much CO². . . . After all, what’s happening is that calcium carbonate is becoming calcium hydrate, and what’s left over is CO².

Soderstrom visits one producer in Quebec, McInnis Cement, which is that province’s single largest carbon dioxide emitter and part of an industry that accounts for 4 to 6 percent of global carbon emissions. Factor in the trucks, tractors, and other machinery used to mine aggregate and to pump concrete into those skyscrapers, and all of a sudden the sector is sitting with the big boys of GHG emissions: electricity and transportation.

Soderstrom also details concrete’s collateral damage — how it enables and perpetuates our environmentally destructive habits. New roads lead to new cityscapes, which lead to more sprawl and higher overall consumption. As far as she’s concerned, we need to curb our use if we are to have any hope of avoiding our impending doom. But instead of offering concrete solutions (you’ll excuse the pun), she only half-heartedly explores carbon taxation; alternative building materials, including wood; and different approaches to urban planning.

While the numbers speak for themselves in Concrete, not much resonates beyond them. This has a lot to do with how Soderstrom organizes her thoughts — around chapters devoted to earth, fire, water, and air. The thematic use of the classical elements is interesting in concept but convoluted in execution. The result is an aggregate of unconnected statistics. But for many readers, even that will be enough to finally reveal the hard facts before our eyes.

Nicholas Griffin lives and works in Toronto.