After growing up in Vancouver, Jack Wang studied in Ontario, Arizona, and Florida before taking up a creative writing position at Ithaca College, in New York. The author of several children’s books, Wang now adds to his bibliography an impressive first book for adults, We Two Alone, with stories that capture significant moments for the sprawling Chinese diaspora. It’s a collection that announces an important new voice in contemporary fiction.

The fast-paced “The Nature of Things” opens in the 1920s with Frank and Alice Yeung, who have “known each other all their lives, ever since they were urchins scrabbling over the one and only playground in Vancouver’s Chinatown.” Then their lives change. With no medical school in the city, Frank travels to Toronto for his degree: “No one was surprised that he wanted to go to medical school, even though he couldn’t be a doctor, not really, at least not in Canada.” After he graduates, the only job open to him is in Shanghai, where the married couple arrive in fall 1936. Frank makes his rounds at the hospital; Alice becomes pregnant. During the Sino-Japanese War, Frank asks his wife to leave for Wuhu, 300 kilometres west of the city, to reside with his aunt and uncle and await him there. No word is heard from him again. In time, Alice escapes from China. Much later, her only grandchild, the son of her own son, will kick a soccer ball on King’s College Circle and walk “in cap and gown through Convocation Hall in Toronto, just like his grandfather.”

In this story, as in five others and a concluding novella, Wang traces the evolution of the Chinese immigrant experience by focusing on individuals, from a sixteen-year-old boy trying to play hockey in Vancouver to an aging actor struggling with his failing marriage and memory in New York City. No matter their age or where they live, these characters are outsiders to the world around them. Even in China, Alice Yeung visits “a little park whose first rule, posted on a sign outside, was The Gardens are reserved for the Foreign Community. All of this made Shanghai feel painfully familiar.”

In “The Valkyries,” which opens the collection, an ominous foreboding hangs over Vancouver: “These days it was risky, leaving Chinatown at night. Just last month a man out on his own had been kicked and beaten. Now that the Great War was over, jobs were scarce, and angry young men were once again roving the streets, seeking rough justice.” Nelson is a young laundry boy who “just wanted to play hockey.” But the coaches ignore his skills and the other players refuse to pass him the puck. Only when disguised as a girl does he succeed at joining a local league. Ultimately, though, he meets that rough justice in both the white and the Chinese community. “Did you think I wouldn’t see this?” the laundry’s owner says when he finally confronts him. “That no one would recognize you?”

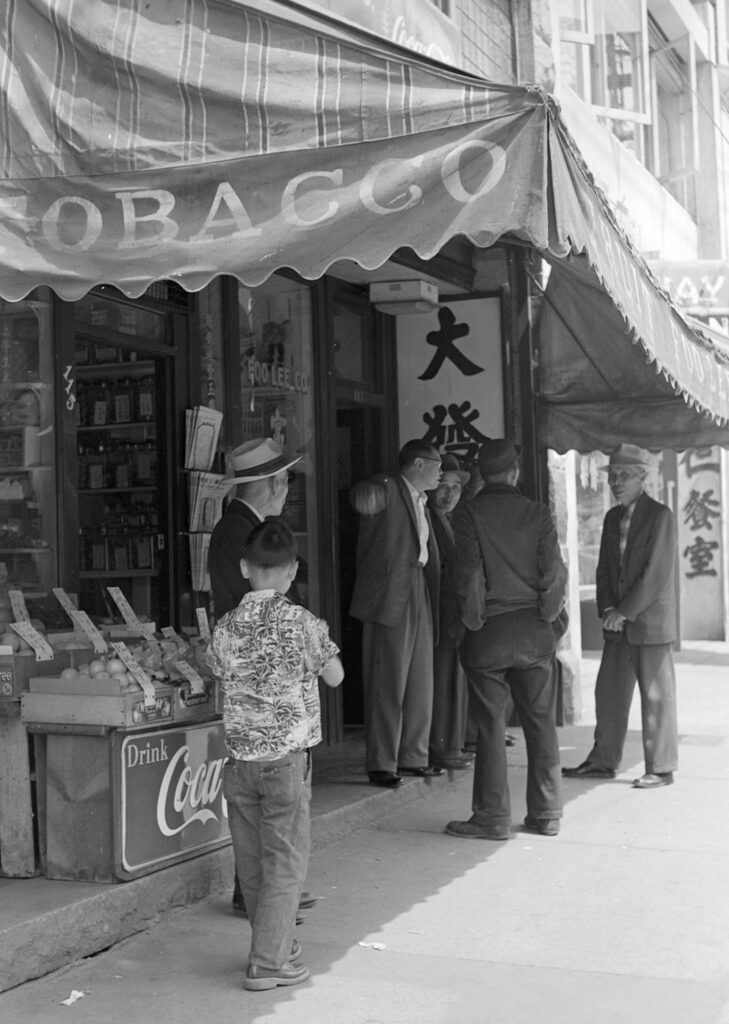

Snapshots of a sprawling diaspora.

Stanley Triggs, c. 1960; Vancouver Public Library (88604C)

“The Night of Broken Glass” is the story of a Chinese consul general in Vienna who tries to save as many people as possible at the beginning of the Second World War. “My father had continued to sign visas until he was found out and a black mark placed in his file,” the narrator says near the end. “I see him still, gazing into the distance, mourning all that couldn’t be saved.”

Wang turns to Kabega, the Chinese area of Port Elizabeth, South Africa, in “Everything In Between.” There a doctor and his family are repeatedly scorned in acts of apartheid-era racism, especially when looking for a new house. “At last Ah Ba said, ‘We’re moving,’ ” the doctor’s daughter recalls. The family abandons South Africa for Australia. “I am, of course, leaving out a good deal. It wasn’t always easy, but we made the best of things.” In Australia, they watch “the final and still more terrible paroxysms of apartness on television” and know they had “done the right thing.”

In “Belsize Park,” the son of immigrants meets a girl at Oxford: “I couldn’t quite believe I had fallen in with someone like Fiona, so clever and lovely and thoroughly English.” But when they visit her home in London, they soon realize their budding relationship can never sustain the forced politeness of her parents. They also know she will never meet his parents, who run a takeout shop in Stoke-on-Trent. “I saw it all,” he confesses as their plans unravel. “The long walk back to the house, the longer train ride home, the baffled looks of my parents.”

Beyond Vancouver, Shanghai, Vienna, Port Elizabeth, and London, the stories in We Two Alone encompass Tallahassee, Los Angeles, and Boston. Wang is committed to rendering his backdrops accurately; with perfectly presented details, he showcases the disharmony of the Chinese diaspora, as individuals endure salient moments in twentieth-century history and more recent times.

With their fully developed characters, authentic settings, and formidable plots, the short stories that make up more than half of We Two Alone paint impassioned portraits of those trapped by the label of “other”— a designation that separates and dislodges, marginalizes and defeats. Beaten, reviled, or abused, these individuals witness and suffer “the paroxysms of apartness” in countless ways.

The closing novella, “We Two Alone,” is the fictional biography of Leonard Xiao, “the founder, director, and lead actor of the Asian American Shakespeare Company.” Narrated in the third person, it weaves back and forth in time, touching upon Leonard’s upbringing, his courtship of Emily Gardner, their childless marriage, their pursuit of acting careers in L.A. and New York, their separation after twenty years, his ambivalent relationship with his father (a Harvard professor), and, finally, his inability to recall his lines: “One moment his mind was full and the next it was empty, like a lake instantly drained, and the feeling was eerie. He scoured his memory, expecting words to leap to his tongue, to rush back in, but none came.” There is no overt animosity here, as there is elsewhere in the book, only the tired responses of a failed and failing man taking refuge in a self-restricted realm.

We Two Alone shows that Jack Wang is a master of the short story, a writer who has mapped his own space, neither Canadian nor American, nor anywhere else. Each episode in this collection is a moving tribute to its characters as well as an indictment of the ostracism that remains when racist taunts and human failures continue to bedevil the modern world.

David Staines is the author of, most recently, A History of Canadian Fiction. He teaches English literature at the University of Ottawa.