The tiny cartoon characters in your pocket have been quietly marching into the future. In many cases, you’d have to look closely to notice. Did you see when the syringe emoji, ordinarily red with blood, turned a whitish vaccine-coloured blue? Or when the face-with-mask emoji, ordinarily with eyes angled downward in unwell distress, suddenly smiled behind the security of its PPE? Like so many others in an expanding palette of icons, emoji have been metamorphosing as they keep up with the times.

Not long after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, something changed on Twitter. Three fists appeared together — tan, brown, black — as a visual sign‑off to the Black Lives Matter hashtag. You couldn’t access the emoji directly on your phone’s keyboard; it was a unique way for the company to show solidarity through automated political punctuation. Months before, Unicode — the international body for information technology standards and the effective governing council of all things emoji — had approved the placard protest sign. It has been put to good use ever since.

Many new emoji are proposed each year, but not all are approved. When one is, each of the major tech players — Apple, Facebook, Microsoft, Samsung, and so on — creates and releases its own spin on the design. The variations reveal inter-company nuance. When Unicode gave the kneeling emoji the go‑ahead in 2019, for example, it did not specify one knee or two. Google and Twitter were unequivocal in interpreting the ambiguity. Their emoji would not appear subservient, humbled, or prayerful on two knees but would instead protest on one, à la Colin Kaepernick. When that placard emoji was given the green light in 2020, Google’s bore an equal sign and WhatsApp’s had a peace symbol. Apple, for its part, issued one that’s conspicuously blank.

What is Apple communicating with its scrupulously unmarked canvas? It may simply be walking the delicate line that all emoji designs must walk, between specific and flexible. The company is more explicit in other choices, however. In what some have interpreted as corporate opposition to gun violence, Cupertino blocked the proposed rifle; the expected blow to interoperability was enough to kibosh that emoji altogether. Apple also quietly altered its pistol when it swapped the revolver out for a Nerf green water gun. And it has introduced a suite of designs to reflect people with disabilities: prosthetic arm, blind person with cane, person signing “deaf” in ASL. Perhaps the move that spoke the loudest, though, was its surreptitious suppression of the Taiwanese flag emoji, which was made unavailable to users in Hong Kong and Macau.

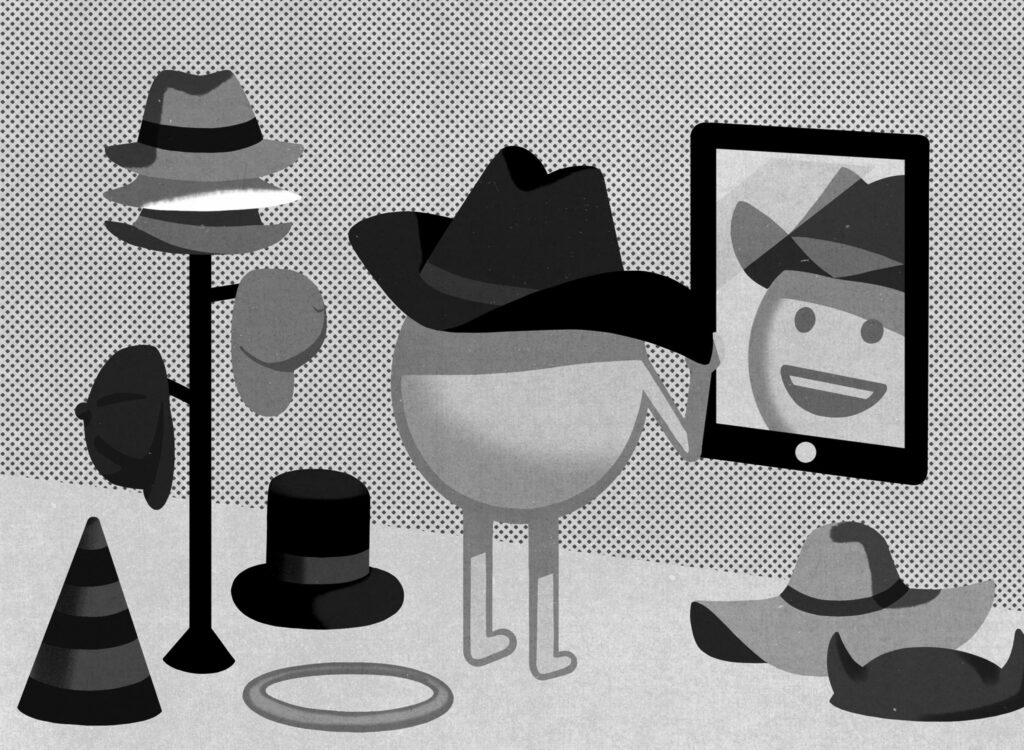

Talking through your hat.

M.G.C.

While Apple championed the disability-themed emoji, others have been at the forefront of different diversity causes. Some of those conversations have been rockier than others. When Facebook introduced a dumpling, for instance, the design brought to mind Chinese bao, the fluffy stuffed buns. Those who first proposed the dumpling objected, insisting the image was meant to be cosmopolitan in look and usage. Facebook listened: its potsticker now resembles something between gyoza and jiaozi. When a team of Googlers introduced gender parity to the otherwise sexist stereotypes of male construction worker and female spa patron, a type designer with Adobe asked why emoji should be gendered at all. He proposed an androgynous third option, later picked up by Google’s creative director for “expressions” and head of the Unicode emoji subcommittee. Henceforth, she said, wherever possible (and there are only six exceptions), her company would release a gender-inclusive version of any person. The commitment meant quite a few new designs, and the move pushed Apple and Twitter to follow suit.

The widely supported interracial couples meant scores of new combinations of gender and race. But consider all the variations that would be needed to truly reflect society. One or more parents may be of various backgrounds, with one or more children, who may or may not be biologically related. If every possible family type were supported, your little keyboard would need quite a few extra bedrooms. It’s partly why the full suite of unions — all 7,230 possible configurations — has been tabled for the time being.

Emoji aren’t without cost: each icon must be designed, and each occupies valuable memory on your smartphone. Besides, even with endless choice in your pocket, you’ll likely use the same handful of favourites in your typical text message. Indeed, usage rates are very much on the minds of the powers that be: just six emoji account for more than a quarter of all the 5 billion that are transmitted each day on Facebook Messenger, for example. The vast majority of the 3,000-odd options are hardly used at all. So the emoji dons are halving their annual additions (thirty net new items, down from sixty) and ruthlessly prioritizing for “global relevance” and expected fashionability.

Many emoji languish in the dark corners of obscurity, while others make unexpected comebacks — called into action by the dictates of current events. The popularity of the microbe soared during the pandemic, while all those airplane emoji stayed grounded. Sobbing was suddenly in vogue, as were pleading face and hands in prayer. More recently, we’ve been expressing ourselves with our multicoloured thumbs, and one can imagine crossed fingers proving invaluable as we begin planning more and more in-person events. While tears of joy and hearts maintain their podium positions, others will surely climb toward the top: the celebratory raising hands, face with party horn, and a checkered flag to mark our crossing of the finish line.

Kevin Keystone is earning his master’s of theological studies at Harvard Divinity School.